This article includes a discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help in Australia, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 and in the United States, call the national suicide and crisis lifeline at 988.

When a pediatrician first diagnosed me on the autism spectrum at the age of 5 in Brisbane, Australia, he told my parents that I would never get a job, never get married, and never move out of their home.

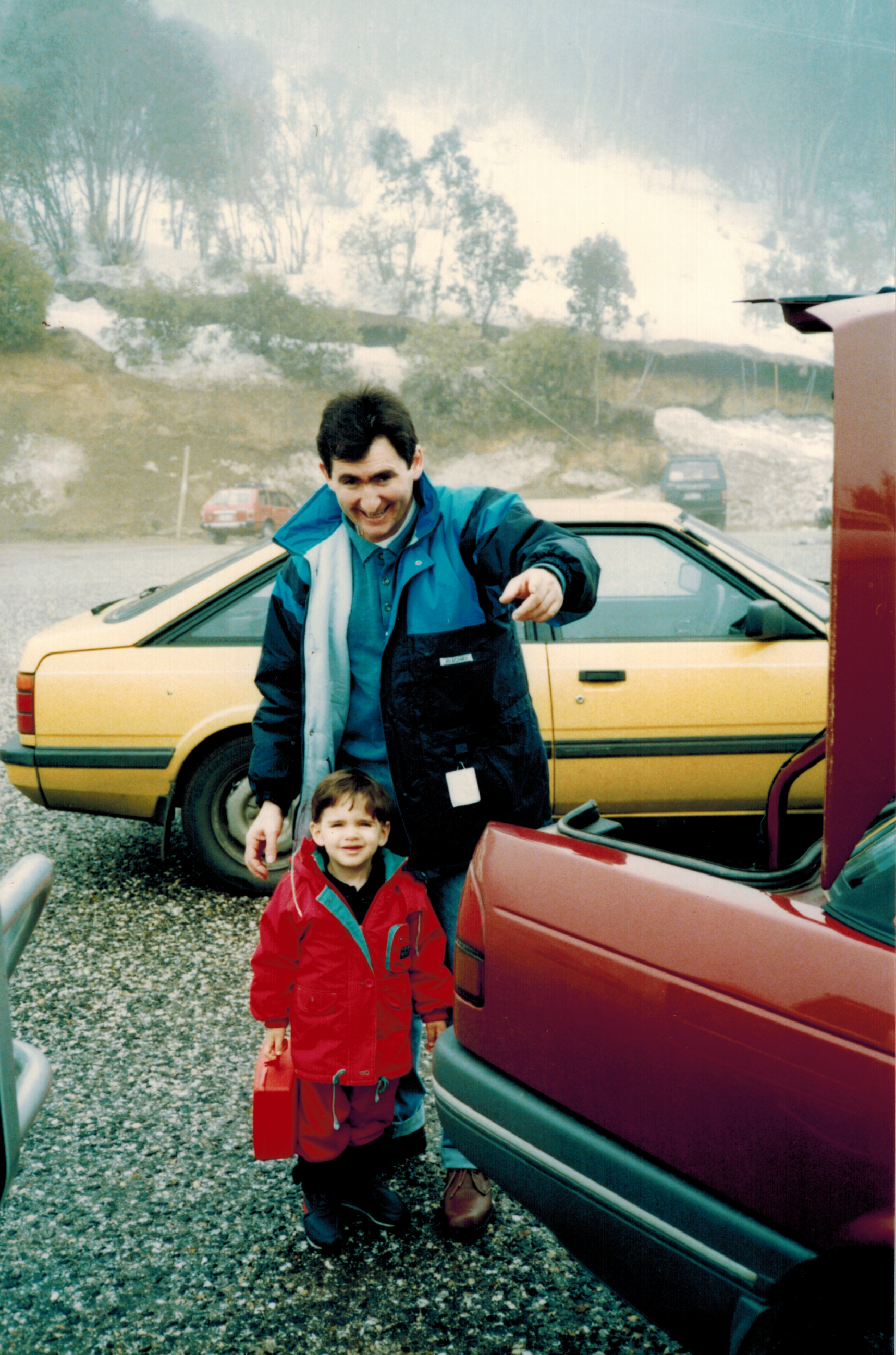

Diagnostic criteria often describe the autism spectrum as a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persisting challenges in social communication, social interaction, and restrictive, repetitive patterns of behaviors, interests, or activities. The pediatrician said I had Asperger's syndrome, which is an old label for a type of diagnosis within the autism spectrum. He claimed that it was rare, occurring in "only 1 in 10,000 people." "My son is not a freak," my dad bit back.

Little was known at the time about the autism spectrum, and for years I had thought my father was reacting out of ignorance. Decades later, I realized what he meant: I was not a "freak"—I was his son. To hear someone describe the core characteristics of someone you love as part of a disorder or syndrome would have been terrible. Being who I was, however, meant that I would grow to face substantial challenges that other children around me would never face.

The Evolving Awareness of the Autism Spectrum

My experience, nonetheless, was more common than I realized. As part of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 Study, a team of researchers and I estimated that 1 in 127 people were on the autism spectrum in 2021, substantially higher than what doctors had told parents, including my own, in the 1990s. Since then, awareness and availability of supportive services has progressed substantially for people on the autism spectrum in parts of the world. Much more information is available now about the diversity within the autism community, hence the development of the term autism spectrum. We now better understand the variation in the conditions' characteristics and support needs, and the prospect of positive outcomes.

Awareness and availability of supportive services has progressed substantially for people on the autism spectrum in parts of the world

After my diagnosis, my mum made it her mission to prove the pediatrician wrong. She began researching what little was known about autism at the time and developed her own resources, such as illustrated story books and task sheets, to help teach me social skills and coach independence.

She advocated for me in school, insisting that I have a teaching aide to facilitate my classes. I was soon enrolled in an autistic therapy school where I, alongside other autistic peers, learned about social skills and emotions. Instructors taught us to read people's faces, to pick up on their nonverbal cues, and to understand the overall context of the interaction to adjust our response and behavior accordingly in conversation. We would role play everyday interactions such as purchasing something from a shop. I attended that therapy school part time alongside mainstream school until I was 10 years old.

An early diagnosis and early support meant that I was able to learn these skills during a critical development period—an opportunity many autistic people do not have globally. Despite progress in awareness and improvements in referral pathways and supportive services, the GBD 2021 Study still estimated the autism spectrum to be within the top 10 leading causes of nonfatal health burden for children and adolescents under 20. The autism spectrum also ranked twenty-first in nonfatal health burden across the lifespan.

One caveat to these burden estimates is that they represent the within-the-skin disability. Many people in the autism community argue that their autism is not a disability, that their autistic characteristics are simply core parts of who they are. They say that their negative experiences from being autistic only result from the way others treat them, a form of social disability. This belief has been a dilemma for me as I lead the work to quantify the global health burden of autism. I experienced firsthand how my autism resulted in considerable challenges growing up; however, most of those challenges were in the way people would react to me.

Ultimately, we live in a world that can be very challenging for autistic people. Many on the autism spectrum need support, such as programs addressing social communication difficulties, social skills training, and life skills and employment training. They need early detection to receive this support. They need to learn the tools to get by, but should do so with a careful balance to not change who they are, and with the space and respect maintained for them to not lose their individuality. In a world where policy decisions are driven by data, particularly from the GBD study's estimates, the absence of a number representing the needs of people on the autism spectrum could mean they are overlooked by governments and resource allocators with the means to provide them support.

The Hidden Burden of Being Autistic

What was not captured by the GBD study is the health burden resulting from the social disability. For many people on the autism spectrum, much of the disability experienced comes from comorbid mental disorders. People on the spectrum tend to have greater difficulty in social communication and detecting and understanding nonverbal cues, making it challenging to form relationships with peers.

Coupled with a hyperfocus on special interests, alongside repetitive and unique motor mannerisms, many autistic people often find themselves victim to risk factors for depressive disorders including bullying, social ostracism, stigma, and discrimination. In primary school, I was the child everyone avoided. I grew up thinking everyone hated me and that I could never say or do the right thing. In adulthood, autistic people can face employment and financial difficulties as well as crippling loneliness.

It was unsurprising when, in a separate study, our team found a significantly elevated risk for suicide mortality among all autistic people—almost three times the risk in the general population. The risk was even larger for autistic people without intellectual disability, who were more than five times more likely to die by suicide than the general population.

These findings highlight the important need to not only provide the autistic people the support they need, but also address this social disability

That study, published last year in Psychiatry Research, was especially important to me. My goal growing up was to one day be accepted as a "normal person." I supposed that perhaps then I would be happy. I would watch other children interact and learn the scripts they used. I would replay conversations in my head again and again. I would force myself through sensory overstimulation.

During high school, I had become so good at masking my traits that others had difficulty identifying that I was autistic. This was a particularly difficult and unhappy time in my life. I was hospitalized in my senior year for suicidal ideation. Although I had felt alone, the Psychiatry Research paper showed that my experience was not unique. I was lucky to have a supportive family and supportive school: Many autistic people go through this experience without these privileges, however. We estimated that 13,400 deaths from self-harm in 2021 were due to this elevated risk that autistic people face, equivalent to 1.8% of all self-harm deaths globally.

In terms of fatal burden, that is, dying prematurely as measured by years of life lost (YLLs), these premature deaths by self-harm robbed autistic people of 621,000 YLLs globally. They caused more fatal burden globally to the autistic population than cocaine use disorders, rabies, or testicular cancer among the total global population. The rate of death by self-harm was similar between autistic males (22.3 per 100,000) and autistic females (20.4 per 100,000), unlike the general population, where males are substantially more likely to die by self-harm than females (13.1 per 100,000 versus 5.8 per 100,000). If this fatal burden were combined with the nonfatal burden estimated by the GBD 2021 Study, suicide mortality would explain 5.2% of the health burden experienced by the autistic population globally in 2021. These findings highlight the important need to not only provide the autistic people the support they need, but also address this social disability.

Thirty years have passed since my pediatrician said I would never get a job, never get married, and never move out of my parent's home. In my adolescence, I was unsure whether I would make it out of high school. Today, I have achieved these milestones. I appreciate that not everyone shares these ambitions and that every autistic person is unique—but these were my goals. I thrived thanks to the early diagnosis, opportunities, and support from my family, teachers, psychologists, and support workers. It was the social disability that almost stopped me. My hope is that my work will lead to real change, supporting others on the autism spectrum who face the same challenges I encountered. By providing key stakeholders the numbers they need for action, we can strive to meet the unique needs of all autistic people, providing them the opportunity to achieve their goals and lead fulfilling and healthy lives.