Contact tracing has long been a pillar of public health here and around the world. With confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States now topping five million, the best hope to recover and reopen is to quickly follow up with individuals who have tested positive, identify their contacts, and guide them on how to safely quarantine to prevent further spread. Testing turnaround time poses a significant challenge to contact tracing because the more time it takes to track and trace the contacts of those who are positive, the greater the chance the virus will spread.

But it's not just speed that matters.

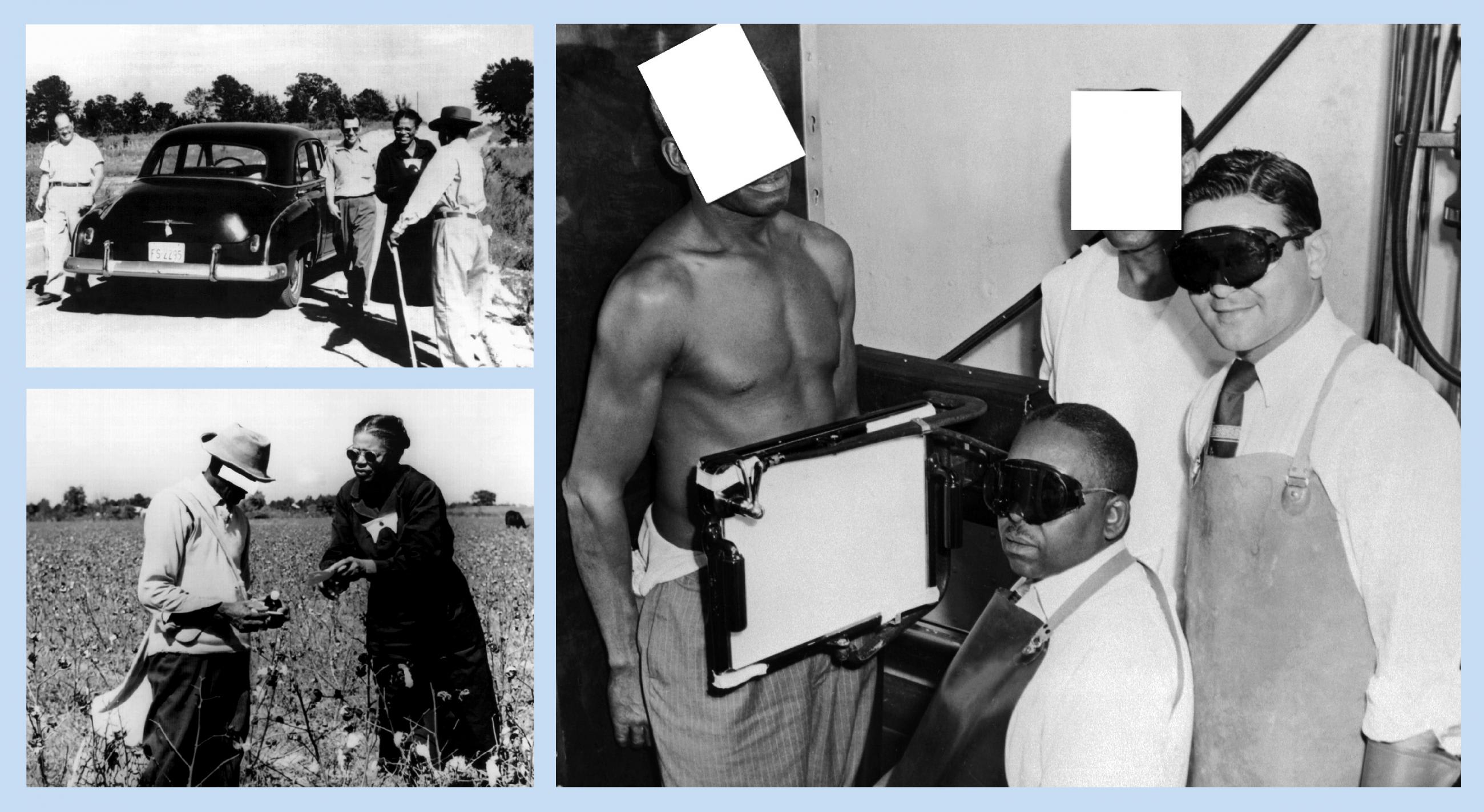

Mindful of the legacy of the egregious Tuskegee experiment and the disparities in health care and health that have persisted for centuries

Black and Latinx communities have been hardest hit by the pandemic and are historically wary of government and health-care institutions. Black people are mindful of the legacy of the egregious Tuskegee experiment and the disparities in health care and health that have persisted for centuries. Their deep and understandable lack of trust in government must be taken into account as states and cities shape their approach to contact tracing. In addition, with national leaders delivering mixed messages and a partisan divide that is widening over issues like mask-wearing, trust in government, especially at the national level, is rapidly declining. An Axios poll in mid-June found that only 38 percent of Americans think the federal government is looking out for their best interests—while just 18 percent of Black Americans feel that way.

If we want contact tracing to be successful, what will it take for the communities most affected to buy in?

Twelve focus group discussions were conducted with a total of eighty-eight participants

To answer this fundamental question, we spoke to a number of focus group participants made up of Black Americans, other people of African descent, and Latinx people in New York and Philadelphia to determine which media messages and messengers would promote participation in contact tracing. Organized by Zebra Strategies, twelve focus group discussions were conducted with a total of eighty-eight participants. They involved recorded sessions led by a psychologist, with each session lasting about two hours and involving six to ten people. The groups included a mix of survey questions and discussion prompts to elicit how people were personally coping with the pandemic as well as their views on how authorities were addressing it. To get at the role communication might play in persuading them to get tested and participate in contact tracing, the groups were shown three different campaign messages to see which one resonated the most and would encourage them to take action.

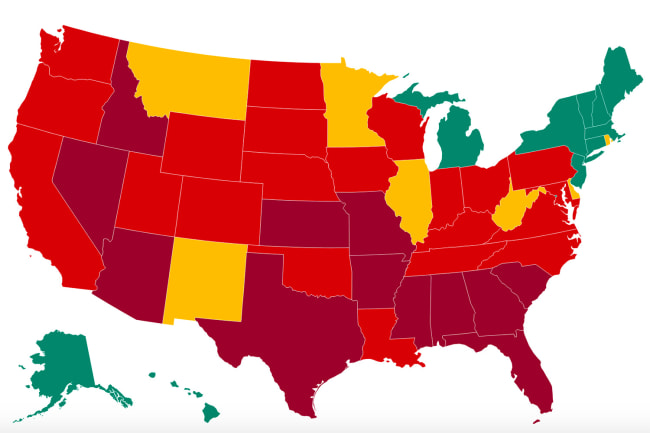

Here's what we learned: One of the most common themes we heard was a sense of a "toppling" of trusted institutions, a disappointment that we are not better prepared as a country, and a shared feeling that those who are in charge are causing or encouraging chaos. The unequal impact of the pandemic—Black and Latinx communities are much harder hit, with higher rates of infection, and Black and Latinx people are more than twice as likely to die from the virus as white people—and the discrimination faced by Black people in so many facets of life all contribute to this distrust.

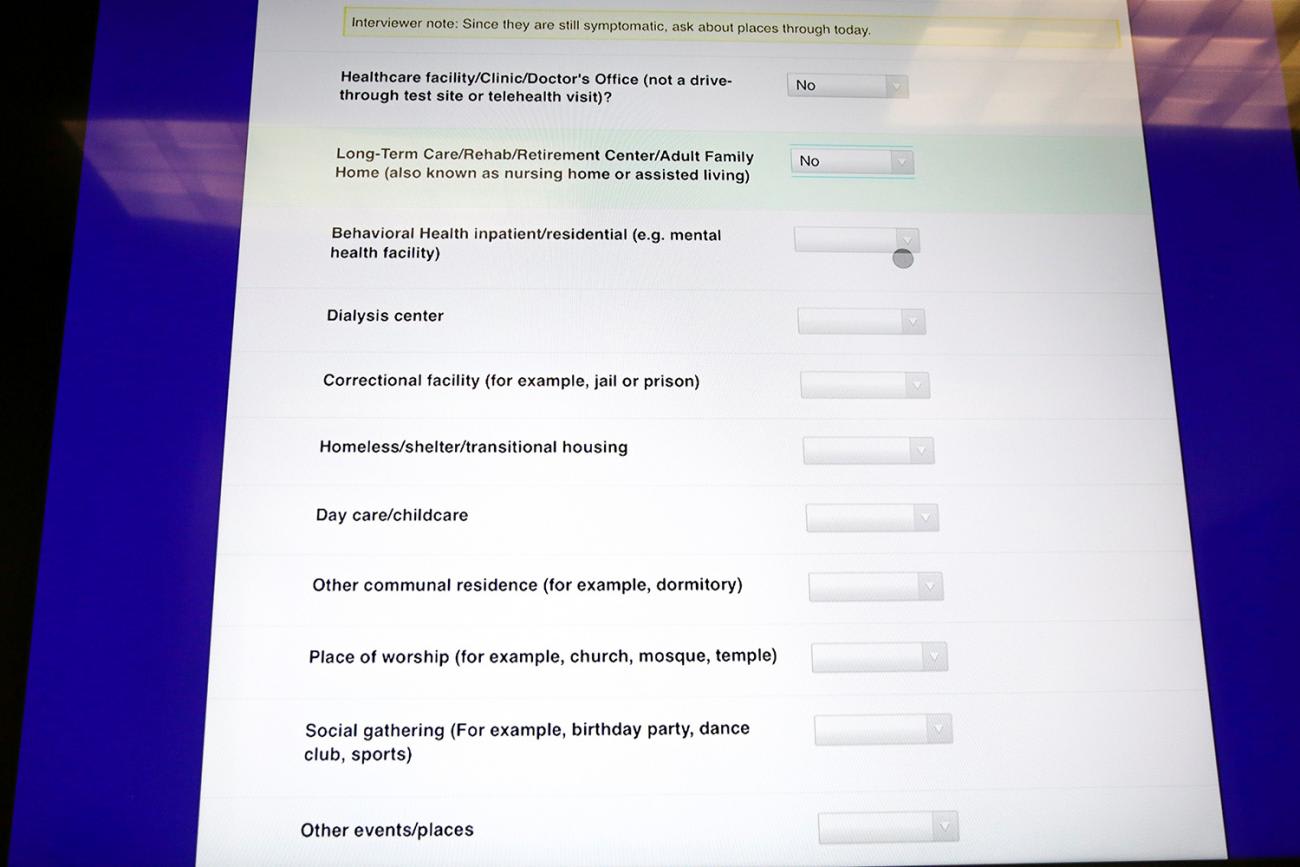

Concerns over possible surveillance, coercion, and privacy infringement

People were also concerned about possible surveillance, coercion, and privacy infringement—with many wondering where the information collected by a contact tracer would go, with whom it would be shared, and how it would be used. There were also fears that the information gathered by contact tracers could be used to deny insurance or unemployment benefits or to take away civil liberties. Similarly, people expressed difficulties talking to strangers (especially when sensitive medical information is being shared), and therefore might not answer a call if they don't recognize the caller ID.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Contact Tracing

Snapshots of a dozen focus groups show surveillance and privacy concerns in COVID-19 contact tracing

Furthermore, there was a shared concern that contact tracing is about "snitching," and that participation could stigmatize those who have COVID-19 and possibly expose them to social ostracization from friends and acquaintances.

A way to look out for "me and my family"

Yet despite these concerns, participants said they are motivated to play their part to help stop the spread of COVID-19 within their communities. Driven by a strong sense of self-reliance and also a desire to contribute to the solution, contact tracing was seen as a way to look out for "me and my family," as one focus group participant put it. As states gear up their contact tracing efforts, here's how they should approach building trust in communities.

Contact tracers should be local. People told us they would be more likely to trust calls from local area codes and from local government officials, including their local health department, than from the federal government.

Local organizations can engender community buy-in. Participants are more likely to answer a call from someone they don't recognize and engage with the contact tracer on the phone if the effort has been promoted, endorsed and reinforced by local organizations that have demonstrated previous care and concern for the community—including churches, mosques, neighborhood groups, outreach programs, health centers, and schools. This suggests the importance of a significant community engagement effort.

Contact tracing needs to be better explained. Few have first-hand experience or an understanding about what contact tracing is, how it works, and who it will help. We must do a better job explaining contact tracing, emphasizing the human connection, underline the fact that it saves lives, and carefully craft messages to debunk myths and model success stories. Participants told us they prefer hearing from those who had contracted and recovered from COVID-19 since they bring a level of authenticity and experience.

Reassure people about confidentiality. The media focus on contact tracing apps may have negatively influenced how audiences understand the effort. People need to be reassured that any identifying information (including their name and address) will be kept secure and will not be shared with their contacts or neighbors, or with housing authorities, immigration authorities, law enforcement, or insurance providers.

Be culturally competent and be empathic. Several respondents said the most suitable contact tracers would be health workers of color and people "who understand them and look like them," because they can engender a much higher level of empathy and trust. All encounters should consider individual circumstances—e.g., financial, social, familial—and be respectful.

Public health authorities are building up the capacity to do contact tracing at the scale that is needed, but it will only succeed if people participate. Just as trust in public health messaging helped "flatten the curve" in some states and countries around the world, we must build trust in contact tracing for communities to have a chance to keep economies open while preventing the future spread and unnecessary deaths of COVID-19.