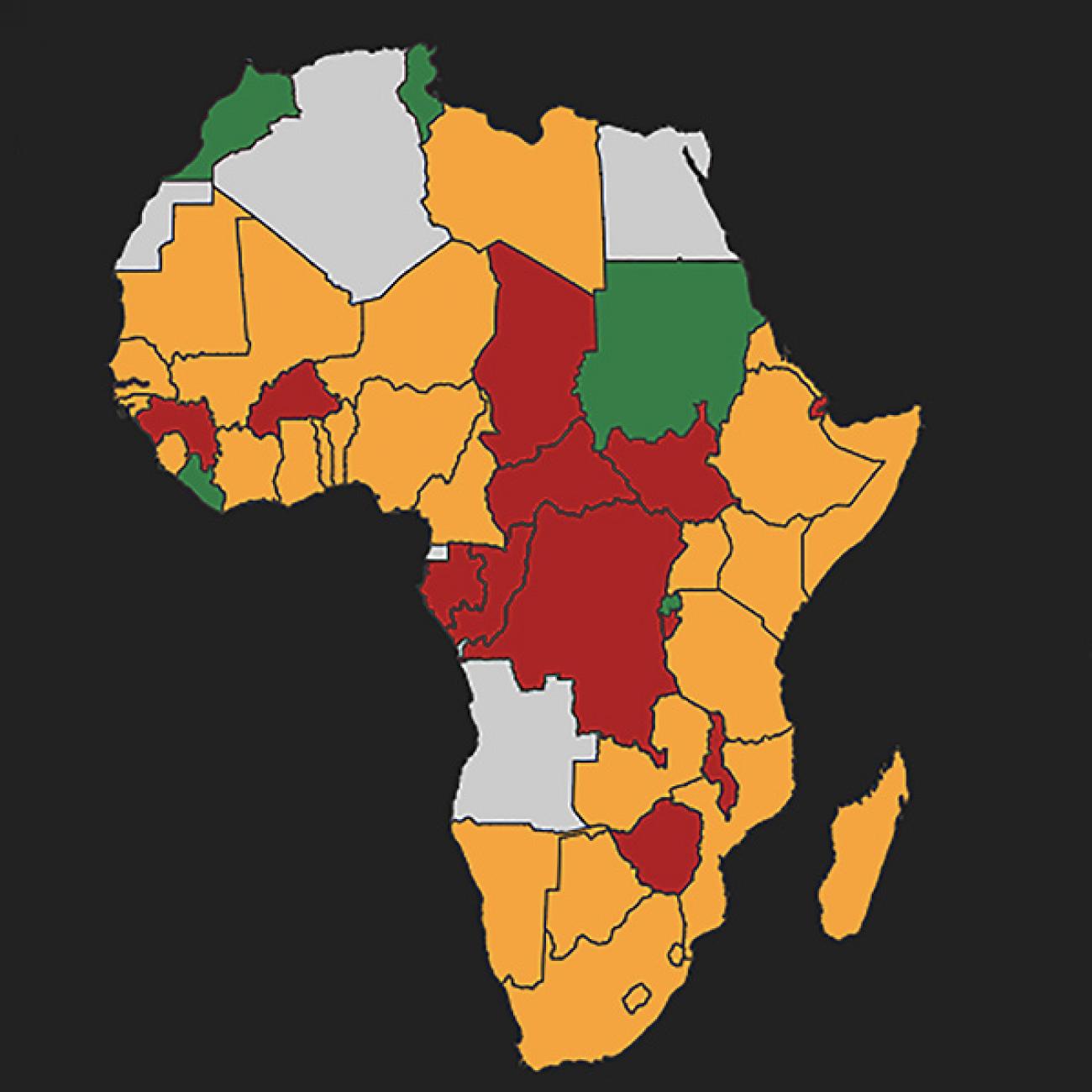

How deep does COVID-19 cut? The novel coronavirus disease has divided the world mostly along hard borders—and to a certain extent along the lines of race or tribe. That much is known. What is completely uncertain at the moment is how far these divisions will go in rolling back the gains made in regional integration and globalization in places like East Africa. Here, as in the rest of the world, responses have been almost completely uncoordinated, with every nation largely fending for its own survival. The United Nations Security Council has toyed with the idea of declaring this a global threat to peace and security. This is COVID-19 unlike health emergencies in the past, including the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, when then U.S. President Barack Obama rallied the security council to collectively help contain the epidemic, has largely polarized global actors.

What's completely uncertain is how far these divisions will go rolling back gains in regional integration and globalization in places like East Africa

For the coronavirus, many countries took time to take a cue from China to restrict movement as a measure of slowing transmission, while others like the United Kingdom considered but later dropped the idea of developing herd immunity. The result has been the unforgiving spread of the virus, with global cases topping 3,087,102 and resulting in more than 212,691 deaths as of April 28. U.S. cases and deaths have spiked, a situation that could have be avoided had lessons from China and history been heeded. The pandemic has also given rise to expressions of xenophobia. U.S. President Donald J. Trump called it a Chinese virus, evoking anti-China sentiments. In the East African region, false allegations were spread on social media of Rwanda sending a sick person in the throes of COVID-19 to enter Uganda and spread the disease.

The lockdowns are effective measures, but they go against the vision of regional blocs of cooperating states—including the East African Community—free movement of everything from people to goods and resources. Instead, borders have been unilaterally closed, and the rapid retreat from regional cooperation has been the first refuge of the pandemic. While the health emergency indeed calls for lockdowns, border closures should have been part of regionally agreed strategies. But member states across the blocks called for cancelation of regional meetings and closure of boarders almost without any regional-level consultations. Indeed, most recently, Uganda has returned confirmed cases of truck drivers from Kenya and Tanzania to their countries after initially not including them in the national count of positive cases. Wouldn’t finding treatment where one tests positive signal greater regional integration?

If there is one lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic for Africa, it's the need to develop modern health care systems for all within national boundaries

The virus has also spurred politicians and government strategists to start thinking about more self-sufficiency, albeit in almost everything, from medical care to capacity to manufacture masks, hand sanitizers. When the storm passes, that thinking could extend to other fields, going against the economic sense of countries concentrating on comparative advantages while leveraging regional cooperation and supply chains for other needs. Indeed, if there is one lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic for Africa, it's the need to develop modern health care systems for all within national boundaries. The pace of transmission and the death toll of the virus has chilled the world and led to reckonings across Africa, as border closures and flight suspensions have meant that powerful and wealthy citizens have suddenly not been able to fly out for medical procedures at high-end hospitals outside their country.

The only thing that has preserved a certain level of regional importance are the multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank. These have largely stepped up to assist their members. It is an infrastructure that the East African Community as well as the other African regional blocs should not lose vision for because of failures at regional response to the COVID-19 health emergency.

Additionally, the coronavirus pandemic has been a rude awakening of the region’s and indeed world’s social inequalities. The disease is infecting everyone from mighty politicians to Hollywood celebrities and from the jet-setting rich to ordinary people from the poorest countries. Whether an eight-month old baby in Uganda or a senior royal in-line for the British throne, anyone can be infected. The indiscriminate infections should be a reassuring reminder that all humans are equal on some level, but instead they often only reveal the cruel, glaring social inequality that looms in the world.

There is little faith in how effective social distancing measures will be in slowing transmission for African cities from Lagos, Nigeria to Kampala, Uganda to Soweto Township in Johannesburg, South Africa—all of which have crowded informal settlements. The lockdowns are challenging given that a big part of the population in sub-Saharan Africa has no savings and lives hand-to-mouth daily.

Indiscriminate infections should be a reminder that all humans are equal, but they often only reveal the cruel, glaring social inequality in the world

The UN has called for emergency help for poor countries, and while that’s desired, it still carries a north-to-south dependency tone and could add to disentanglement sentiments in the COVID-19 pandemic's aftermath. That notwithstanding, African countries have taken the social distancing message to heart, they can’t afford to gamble with experiments like the U.K.’s herd immunity. Uganda, for example, shut down schools and places of worship even before confirming a single COVID-19 case. Is it time for us to reflect on what matters for humanity—perhaps taking lessons from princess Sofia who has temporarily set aside her tiara to work as a medical assistant in support of the fight against COVID-19 in Sweden?

How should we use available resources to bridge the inequality gap? These are the questions we should be asking. Yes, COVID-19 has divided us and it will challenge unions, but the baby shouldn’t be thrown out with the bath water.