The response to COVID-19 has revealed the fundamental shortcomings of health systems in every country—big and small, rich and poor. Among the lessons that will someday be written is that it has been difficult for weak health systems to react through public health measures, including epidemiological surveillance, analysis, and control, especially in countries with limited political stability and therefore little continuity in policy. It is possible that the common essential flaw in some of the hardest-hit middle-income countries lies in the lack of political commitment to public health, health promotion and prevention, and primary health care. In countries without universal health coverage, such as Ecuador, this becomes even more evident when coupled with a lack of scientific input. On the contrary, countries such as Costa Rica in Central America, with a more robust public system that provides medical attention through universal social security, uncertainty was also reduced by a science-based political will to contain the spread of COVID-19.

Ecuador is suffering from the impact of COVID-19, with a case fatality rate of 4.8 percent

Chile, with national health services dating back as early as 1952 that evolved into a solid national public health system, saw massive protests against its persistent inequalities and barriers to medical attention in October of last year. Still, this South American country's COVID-19 figures signal the pandemic is under control, with a low case fatality rate of 1.09 percent (82 deaths out of Chile's 7,525 confirmed cases as of April 13), and a high number of gold-standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests (85,035, or 44.48 per 10,000 people) by April 13. Similarly, Costa Rica has 612 cases and only 3 dead, or a 0.5 percent case fatality rate on the same date, although they only have results from 6,868 PCR tests (13.48 per 10,000). In contrast, Ecuador is suffering from the impact of COVID-19, with a case fatality rate of 4.8 percent (355 deaths out of 7,529 confirmed cases), from a total of 24,553 PCR tests (only 13.92 per 10,000) by April 13.

COVID-19 in Chile, Costa Rica, and Ecuador

Chile and Costa Rica both have a low case fatality rates while Ecuador's is much higher

Basic Health Setbacks

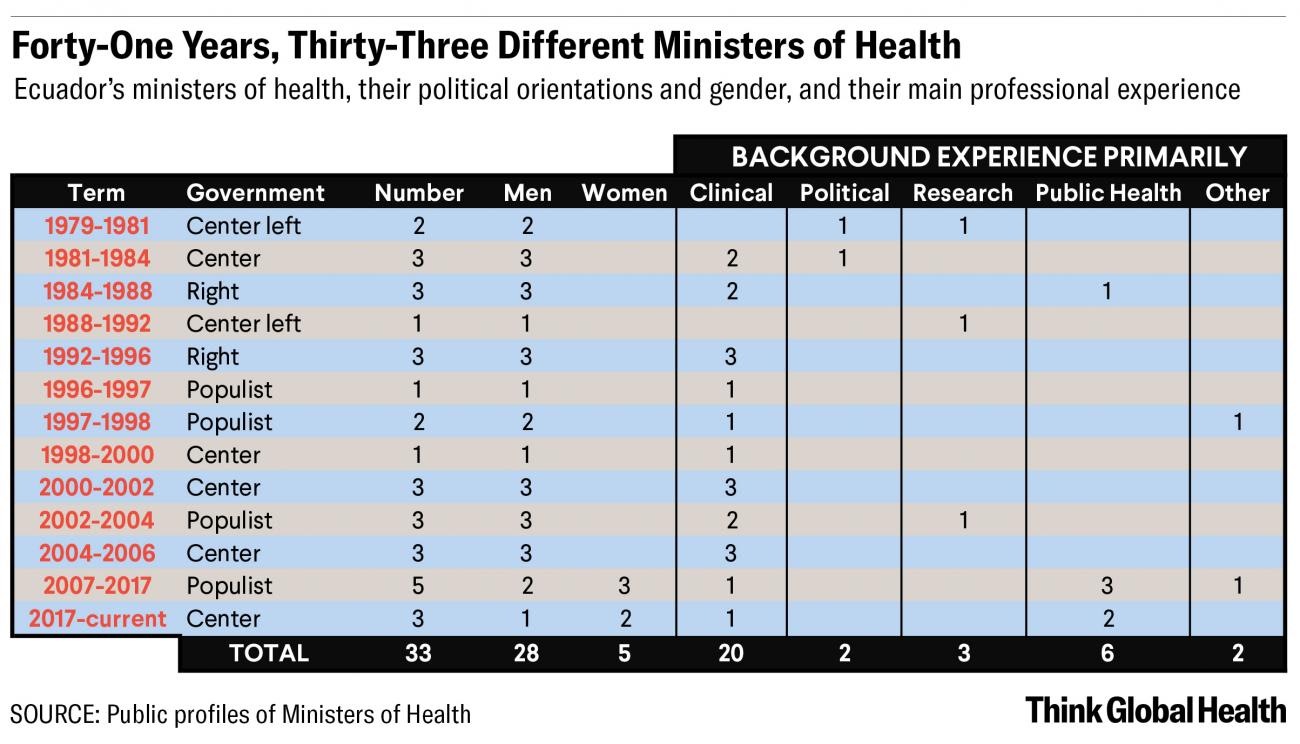

In Ecuador, an upper middle-income country, instability has defined the country's Ministry of Public Health for years. It was late to the region, created only in 1967, later than other Latin American and Caribbean countries. Since then, the ministry has undergone frequent transitions of presidents and ministers of health, who have had a variety of backgrounds whose one common thread is their general limited experience in public health. This revolving door of leadership has contributed to discontinuity in policy and has had an impact on public health of people in the country. More than forty years since the World Health Organization (WHO) made the first call [PDF] for political commitment to primary health care as a means to universal health coverage, decision-makers in Ecuador still fail to prioritize [PDF] primary care.

This revolving door of leadership has contributed to discontinuity in policy and has had an impact on public health of people in the country

Basic health coverage has even experienced setbacks in achievements from recent years, and almost 50 percent of total health spending remains private. As a result, compared to the regional average in the Americas, Ecuador is behind in immunizing against polio and measles-mumps-rubella (84 percent and 81 percent, respectively), reducing teen pregnancy rates (78.8 per 1,000 in Ecuadorean women aged 15–19); eliminating stunting in children under 5 (23.9 percent); and providing people with access to safe sanitation (42 percent). In good measure, these problems originate in the absence of any solid state policy that prioritizes public health issues and primary health care—coupled with corruption in a country characterized by a tolerance for it [PDF]. Similar to other low- and middle-income countries, Ecuador also has limited knowledge integration in policymaking, including community-based informed and collaborative processes.

Although through the years Ecuador erected certain pillars among its health programs—effective social participation in favor of maternal health, for instance, and the establishment of local health councils—these initiatives did not survive administrative changes and were abandoned. It is possible that a lack of structured and sustained scientific and technical analysis may have limited the power of civil society to demand clear and strong political commitment to primary health care. In addition, because voting is mandatory in Ecuador, if public debate cannot place this conversation at the forefront, elected politicians may not view universal health coverage, primary health care, and public health issues as a significant concern.

Ecuador's political pendulum has swayed between the far right and center left in different major intervals

Having a four-year presidential system, Ecuador's political pendulum has swayed between the far right and center left in different major intervals. The first was a period of political orientation ping pong from the end of the last military dictatorship in 1979 until 1996. The second was a time of heightened social unrest coupled with the rapid overturning of governments and seven different presidents until 2007. The third period was a decade characterized by presidential stability until 2017—though even then, the populist government oversaw five different ministers of health. And finally, we are in a new period under the current administration, which originally maintained the previous minister of health but eventually replaced her.

High Instability in Health Leadership

In a period of forty-one years, Ecuador has had thirteen presidents (all men, except for a woman serving as acting president for four days) and a total of thirty-three ministerial tenures (only five women have held the post), with only one minister remaining for an entire presidential term of office, and only one serving in two non-continuous terms of office. Such high instability in political leadership, including in the health sector, within an equally uncertain legislative context, has made it difficult to find ways to position primary care "on the road to universal health coverage." In addition, most ministers of health (a total of twenty) have had a background mainly in hospitals and clinical practice, with fewer than half having more experience or specialized knowledge in public health (a total of nine). Of course, the latter is not a guarantee for scientifically guided decisions; ministers with research or policymaking experience can very well have this capacity.

During the longest presidential term, 2007–2017, health budget increases were steered toward hospitals in big cities

Concurrently, continuity itself cannot ensure an adequate approach. The only full term of office with a single minister of health was between 1988 and 1992, and it gave an impulse to primary health care, creating more than 500 primary level units and hiring 1,500 health workers. Correcting the errors of the past, however, and setting a solid path forward required more time than politics allowed. During the longest presidential term, from 2007 to 2017, increases in the health budget were favorably steered toward hospitals in big cities, giving them an advantage compared to the primary level of care and contributing to the expansion of a lucrative private sector at the public expense. To illustrate this, a single hospital in Quito increased its income from $15 million in 2010 to $45 million in 2012, and another in Guayaquil increased its income from $1 million in 2009 to $31 million in 2012.

To reduce the possible effects of frequent presidential and ministerial transitions on Ecuador's capacity to strengthen public health and achieve universal health coverage, a mechanism for consistently supporting research as a crucial operational lever is needed. An independent commission dedicated to knowledge translation, for politicians and their social and civil counterparts to develop the capacity and will to make informed decisions, could aid in reducing uncertainty and discontinuity by ensuring that all stakeholders are able to contribute more coherent, transparent and accountable policy—scaffolded by academic, scientific and technical debate.

A mechanism for consistently supporting research as a crucial operational lever is needed

In the strictly political arena, a long-term multi-party commission complying with minimum academic, technical, and scientific requirements could help reduce sectarian decisions and compel politicians to work more closely with researchers, communities, social organizations, and movements, which are currently contributing in a dispersed manner. One example of this is the civil society commission in Colombia, which has the responsibility of overseeing health reform. Another is the scientific parliamentarian offices in Great Britain and Spain, which work to inform decision-makers. A similar commission could assist novel and experienced politicians and activists in Ecuador in learning about the international commitments and frameworks by which the country abides, and the existing or needed scientific evidence for reforming the health system.

In the COVID-19 response, for instance, among other scientifically based potential courses of action, a commission like this could help Ecuador develop a coherent national strategy of locally based community epidemiological surveillance, so that each local government can adapt it to its reality and make relevant decisions. Data could be collected and analyzed locally, according to the political divisions of the country, and aggregated progressively to the national level. This would become the basis of a strategy to progressively exit the current lockdown, with the view of strengthening a sustainable public health answer beyond endemic and external threats. In particular, it could help to build a pedagogical approach that empowers local populations instead of relying on the figure of a controlling and punishing government.

… to help to build a pedagogical approach that empowers local populations instead of relying on the figure of a controlling and punishing government

This commission, which would have to define its goals and structure, possibly emphasizing long-term stakeholder relationships, could assist in making decisions and becoming more transparent by enabling both monitoring and accountability—thereby also guaranteeing democratic and empowered participation in the process. In addition, it could move the debate away from the central health authority to include local governments; professional, scientific, and public health associations; civil and social organizations including the indigenous movement; communities; as well as opinion leaders and private sector representatives such as the Ecuadorian Business Commitee (Comité Empresarial Ecuatoriano), which may challenge the cause for public health and primary health care.

It is possible that a built-in academic and scientific mechanism achieving political choice for primary health care relevance in executive and legislative decisions can be as successful as independent efforts have been in the past when working in favor of, for instance, the UN 2018 General Comprehensive Law to Prevent and Eradicate Violence Against Women, the reform to give treatment coverage to orphan and catastrophic diseases, and the (unsuccessful) vote to legalize elective abortion in cases of rape. The commission would need to focus on the implementation of universal health coverage rooted in primary health care, while striving to include an interdisciplinary approach to address wider social and economic factors.

Thinking toward the future, the country needs to build a more coherent, transparent, and accountable health system

A broad, multidisciplinary, independent commission such as the one proposed here could have helped to ensure that different stakeholders contribute to a more robust response to COVID-19. Thinking toward the future, the country needs to build a more coherent, transparent, and accountable health system leveraged by wide political support from national decision-makers beyond circumstantial and partisan conditions. This commission would help to address local needs—as well as wider social, political, and economic health determinants—and assist in monitoring and evaluating the results of programs in the country, making Ecuador's health system better prepared to confront new or persistent local and global threats.