Malawi has a unique claim to COVID-19 fame: it is the only country in the world to announce a lockdown, and then cancel it before the restrictions came into force. President Arthur Peter Mutharika declared a state of emergency on March 20 before health authorities reported any cases in the land-locked southeast African country. Three weeks later, with sixteen confirmed cases and two deaths recorded, Mutharika announced a twenty-one-day lockdown, starting on April 18. The new rules were to include shuttering central food markets and non-essential businesses, restricting hours for farming, and allowing public transit only for hospital staff and emergencies.

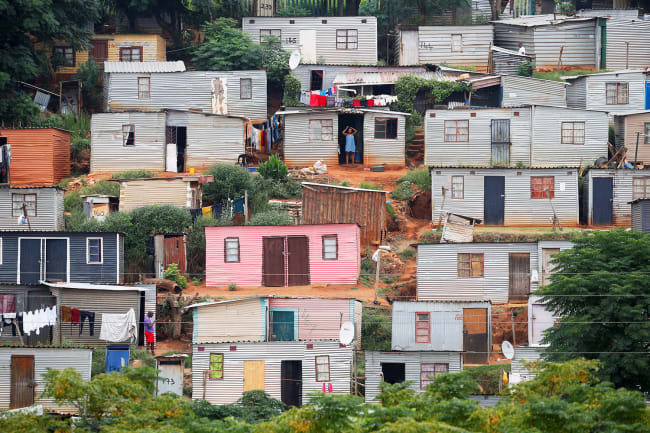

Malawi has a GDP of just $389 per person, the third lowest in the world according to the World Bank

But Mutharika, who has been embroiled in a political crisis since the country's top court nullified last year's election results in February, misjudged the sentiments of many of Malawi's over 18 million inhabitants. Malawi has a GDP of just $389 per person, the third lowest in the world according to the World Bank, and the lockdown announcement sparked a wave of protests. Led by business owners and street vendors, citizens called attention to the fact that further economic sacrifices would be devastating for a nation already battling malnutrition and infectious diseases and recovering from the damaging effects of last year's Cyclone Idai.

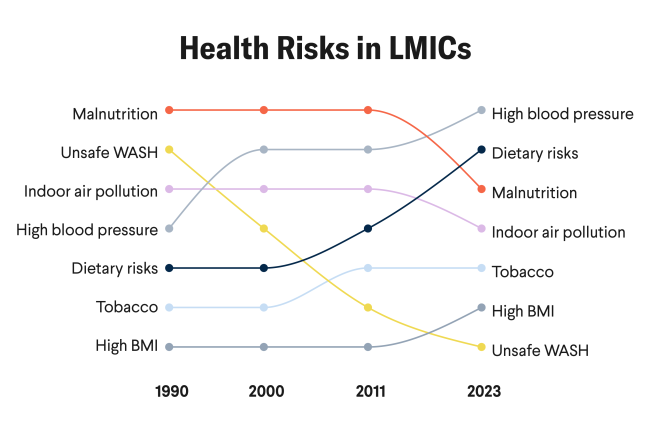

Titus Divala, an infectious disease doctor at the University of Malawi College of Medicine, noted that the main killers in Malawi—HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria—all demand that people present to health facilities. "There is a big danger of losing more lives from a lockdown," he said. "It would be a big gamble."

There is a big danger of losing more lives from a lockdown

Titus Divala, U.Malawi College of Medicine

The day before the lockdown was to take effect, the Malawi High Court granted an injunction overruling the president's decree. The Malawi Human Rights Defenders Coalition, an activist group that launched the case, argued in a petition to the court that the restrictions would drive many Malawians into hunger and put them at risk of other diseases, potentially causing many more deaths than COVID-19. "We are not against a lockdown, but a lockdown without social support for Malawians would be meaningless," said Victor Mhango, director of the Centre for Human Rights, Education, Advice and Assistance in Blantyre. "What Malawians need is a government to support them before a lockdown."

Besides the health and economic risks, the political controversy over the lockdown order fueled public skepticism of Mutharika's motives. Although he was declared the winner of last year's election, the High Court saw evidence of numerous irregularities, such as the use of white-out to alter votes.

Disputed results in last year's annulled presidential election led the High Court to call for a new vote on Jun

Mutharika, who leads the centrist Democratic Progressive Party, became president in 2014, two years after his predecessor, who was his brother, died in office and Vice President Joyce Banda assumed power. The Malawi Electoral Commission declared Mutharika the winner of last year's election, but the result was disputed by his two main opponents, Lazarus Chakwera of the Malawi Congress Party and Saulos Chilima of the United Transformation Movement, who is also the current vice president. The two urged the High Court to order a fresh vote, which it did.

Under the court order, that vote is scheduled for June 23. Chakwera and Chilima have now joined forces to challenge Mutharika. Other critics have accused the president of ordering the lockdown as a ruse to gain political advantage from the pandemic by discouraging voters from registering for the election re-run.

…they were playing with peoples' lives in the heat of a political campaign

Sunduzwayo Madise, dean of the U.Malawi law school

Sunduzwayo Madise, dean of the University of Malawi law school, said that while no one opposes a lockdown for public health purposes, the proposed restrictions could have harmed those without access to adequate financial or other support systems. "With the lockdown, you could say that they were playing with peoples' lives in the heat of a political campaign," Madise said. Instead, "the government must put in place mechanisms to ensure there is a safety net for those people who would otherwise suffer."

Mutharika has responded to the criticism by promising emergency cash payments financed by the World Bank for at least 172,000 households in and around the largest cities. The World Bank has pledged $37 million for COVID-19 relief measures in Malawi, but whether these particular payouts will curb hunger or the spread of COVID-19 is open to question. Over twelve million Malawians already live below the international poverty line, yet just 1.4 percent of them would benefit from the emergency aid.

Over twelve million Malawians live below the poverty line—just 1.4 percent of them would benefit from the emergency aid

Meanwhile, the United Nations has launched an emergency appeal for another $140 million in foreign aid to support the government's National COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plan for the next six months. Half of the funds will be earmarked for food security and social support. As of June 9, Malawi had recorded a total of 455 COVID-19 cases, with just four deaths. But only fourteen testing sites had been set up, and they had conducted fewer than seven thousand tests. According to a model created by the Kuunika Project, a program funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to produce high-quality health data, 85 percent of Malawians could be infected over the next year.

Given such dire forecasts, health care workers fears triggered a two-week sit-in at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, the country's largest medical center, and forced the hospital to turn away patients. Another big hospital, Kamuzu Central Hospital in Lilongwe, the capital, was left with a skeleton staff after nurses and doctors boycotted work in a bid to force the government to increase their risk allowance from 1,800 kwacha ($2.40) a month. The protests paid off when the authorities agreed to a raise of up to a maximum of 60,000 kwacha ($81) a month.

A shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) has also heightened tensions. "Health care workers had to go on strike to literally beg to be protected, to be given masks and aprons and uniforms," said Dorothy Ngoma, past president of the National Organization of Nurses and Midwives. "Even now, not all of them are protected."

Collins Mitambo, president of the Medical Doctors Union, agreed that a shortage of PPE remains a major problem, noting that some doctors have been told to use the same N-95 mask for a week.

According to one model, 483,000 Malawians will require hospital treatment, including 85,000 needing critical care

Like many other impoverished countries, Malawi faces a huge challenge in preparing for a further spread of COVID-19. The Kuunika model projects that 483,000 people will require hospital treatment, including eighty-five thousand needing critical care. Yet, as of early June, the entire country had only seventeen ventilators and twenty-five intensive care beds. Beyond this, a study of 255 hospitals in Malawi showed that just a quarter of them had a reliable electricity supply, just over half had hand soap, and only one-third had oxygen supplies. Raphael Kayambankadzanja, a critical care nurse at the College of Medicine who led the study, noted that even where there was equipment, there were still problems.

"We found very little equipment in terms of basic critical care," he said. "Some hospitals say they have the equipment, but it is not functional, which means you can't use it properly."

Besides equipment, Kayambankadzanja worries about a shortage of hospital staff trained in intensive care. "It's not just putting a patient on a ventilator. The ventilator is the last of your worries. Patients require a lot of sedation, and a lot of support," he said.

The population is following some of the advice that is given out, which may be very good for COVID-19, but very bad for many other diseases

Titus Divala, U.Malawi College of Medicine

Malawi also faces the risk of a spike in deaths from other diseases as ill patients stay at home rather than risk being infected by COVID-19 at a clinic or hospital. The Kuunika analysis points to a 50 percent jump in deaths from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and maternal and child deaths. That translates to twenty-seven thousand more deaths from these causes over the next year as a spillover effect of COVID-19. "What if they have tuberculosis and they're coughing?" asked Divala, the infectious disease doctor at the University of Malawi College of Medicine. "We have already noticed that the number of tuberculosis cases we are detecting now is much lower than at this time last year. The population is following some of the advice that is given out, which may be very good for COVID-19, but very bad for many other diseases which kill more people than COVID-19."

A setback in the fight against HIV/AIDS, the other present-day pandemic, would be especially damaging. Since the country's first case was identified thirty-five years ago, Malawi has emerged as a global leader in the treatment and prevention of HIV. It is close to achieving the United Nations' 90-90-90 targets: 90 percent of people with HIV/AIDS knowing their status, 90 percent accessing antiretroviral drugs, and 90 percent on those on antiretrovirals achieving viral suppression, meaning that the drugs are effective in managing HIV.

Malawi has emerged as a global leader in the treatment and prevention of HIV

"With the initial fight when HIV hit Malawi, there was a lot of strong political will," Mitambo, the doctor's union president said. "Some of the politicians would do testing in public to show that they are committed. There was a role that politicians played, advocating for better health for Malawians." Now, in the battle against COVID-19, politicians are again playing a big role, though a less constructive one. With the election around the corner, political rallies are amplifying the risk of infection, yet few people wear masks in the boisterous crowds. The threat of COVID-19 is in plain sight in an already vulnerable setting, but Malawians are aware that the outcome of an election can also dictate the health of their country.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Both authors are involved in unrelated research at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital and the University of Malawi College of Medicine, institutions which are mentioned in this article.