Last month, I had an interesting conversation with my mother Ujwala Rajgopal, who is a practicing general surgeon in San Diego, about the pandemic. After our normal greetings and catch up, we went down a rabbit hole of wondering how, in this day and age, COVID-19 had spread this far. Don't we as a society have the data and technology available to better track and control epidemics? Data and technology basically rule our lives, so why aren't they being used more effectively in the health care field?

Why don't we have a single global surveillance system that documents existing and emerging diseases in every country?

As globalization continues to increase, epidemics in the 21st century are spreading faster and farther than ever. The COVID-19 outbreak has shown that we can no longer afford to focus solely on domestic health care issues when it comes to the spread of infectious diseases. However, the potential for revolutionary health technology has also spread fast and far over the past two decades, as internet and mobile phone usage have nearly doubled worldwide from 2014–2019. So why don't we have a single global surveillance system that not only documents the occurrence of existing and emerging diseases in every country around the world, but also analyzes data (read: new data) to provide more accurate, sophisticated models on the specific timing and geographic distribution of disease outbreaks and epidemics?

One answer: it's too complicated. My answer: let's start somewhere.

What Exists Today?

From a bird's eye view, infectious disease surveillance around the world originates at the local level. For example, in the United States, health care workers use clinical records and lab reports to conduct surveillance on disease outbreaks and collect data on confirmed cases. However, this requires local facilities and workers to have a uniform clinical definition of a reportable disease (simple for an existing disease like measles and difficult for an emerging disease like COVID – 19) and the available laboratory resources to make such diagnoses. Local health care professionals report diseases to the county or state, and administrators at that level make decisions regarding assessment, response and notification to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other national or international bodies.

Internet and mobile phone usage have nearly doubled worldwide from 2014–2019

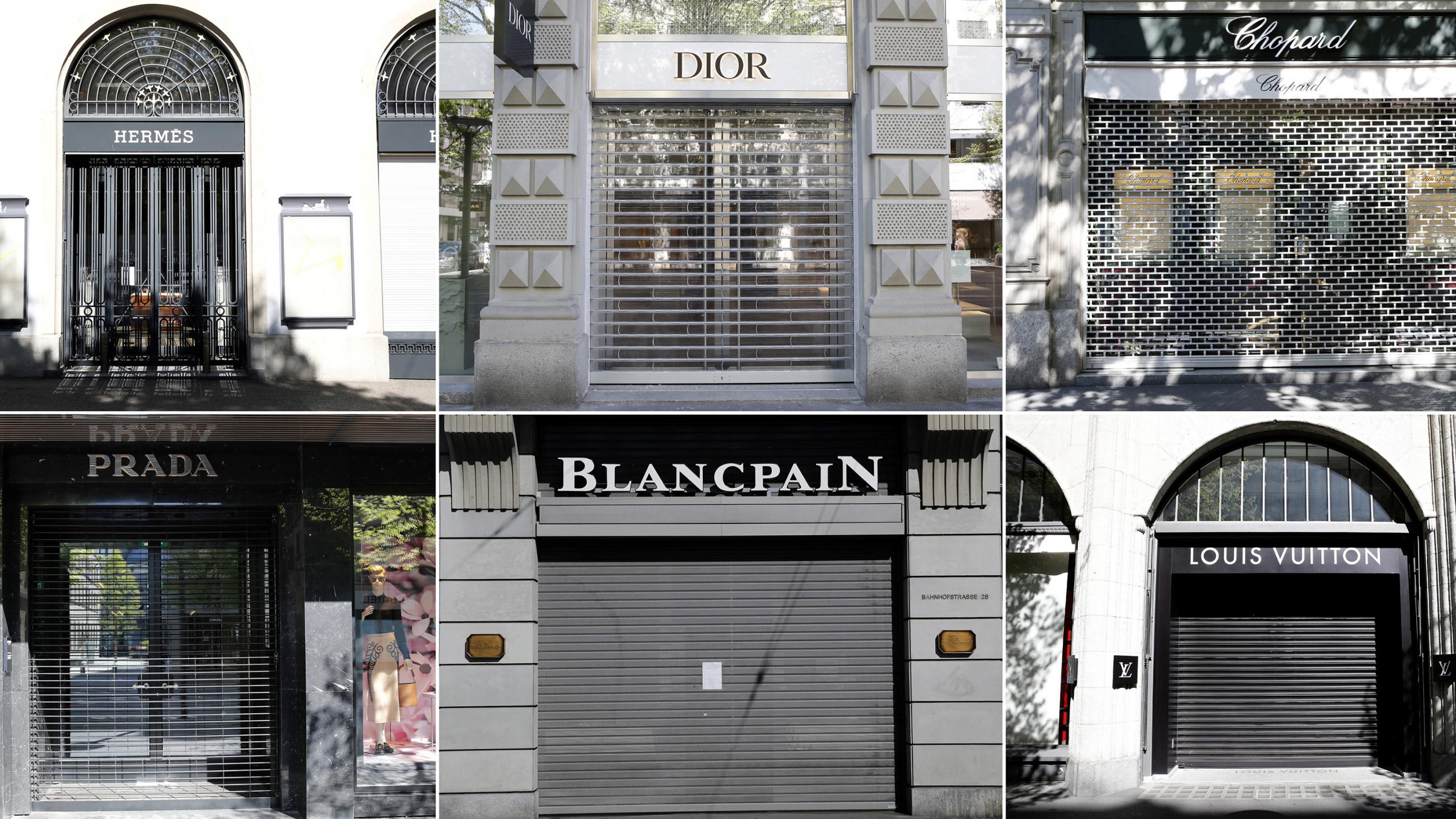

That's where it gets complicated. Even if clinical definitions and reporting requirements remain unchanged from state to state, disease burdens, surveillance infrastructure, and funding varies. Between countries, the differences may be even more stark. With the varied quality of national internal reporting, lack of financial resources to strengthen health systems, and inconsistent surveillance methods from country to country, it's no surprise that there is slow progress with these methods. The sometimes secretive nature of governments delaying disease reporting to the World Health Organization (WHO) due to the fear of economic repercussions and political embarrassment only adds fuel to the fire and risks further promulgating emerging infections and subsequent financial market chaos.

Again, let's start somewhere. Consumer behavior and demand is relentlessly tracked nowadays, so why not do the same for health? It's almost as if Instagram knows what TV show I need to watch next or what skin care product I must buy before I know what I want.

Consumer behavior and demand is relentlessly tracked nowadays, so why not do the same for health?

Remember when Target knew women were pregnant before their family members knew they were? Could this model play a larger role in our public health surveillance infrastructure? What if new data sources that better model traditional patient behavior were integrated into existing surveillance infrastructure, to extrapolate details on the specific timing and geographic distribution of an emerging disease? For example, if I am not feeling well, I might surf the internet, looking up my symptoms. I might then go to the drugstore and buy some over-the-counter medicine. By scouring through internet search queries and social media for terms like "flu" or specific symptoms, researchers have been able to model estimates and predict epidemic alert levels that are highly correlated with actual disease incidence.

But what if your behavior, online and in stores, fed disease models? By identifying things like surges in the demand of over-the-counter medical supplies that then triggers an alert within the local public health department for immediate further investigation, we could take more proactive steps to early disease identification and response.

What if your behavior, online and in stores, fed disease models [and helped] early disease identification and response?

A recent article published by the Washington Post is a perfect example of how a system like this could have at least alerted local officials to take immediate further action. Michael Bowen's medical supply company Prestige Ameritech based in Texas experienced a nearly 35,000 percent surge in online orders for medical masks in mid-January, right before COVID-19 took a strong hold in the United States. Had this surge triggered an alert within a responsible public health body, perhaps the United States would have been better prepared to fight this disease. However, Mr. Bowen did exactly that. He alerted top administrators within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, allegedly only to have his pleas fall on deaf ears—a claim that is part of a new whistleblower complaint by the former director of the U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority agency.

Unfortunately, how government leaders react and respond to public health threats is out of the control of an ordinary citizen. What we as a society do have control over is better utilizing technology and health informatics to provide another data set for public health experts to use in their models to make risk assessments and guide their response.

Implementing such a system would require several things.

- Developing a list of applicable medical supplies and corresponding location-specific metrics.

- Taking inventory of the supply and demand of these supplies on a timely basis.

- Creating appropriate risk assessment plans and coordinated responses.

What we as a society do have control over is better utilizing technology and health informatics to provide another data set for public health experts

By mirroring something like the NPLEx tracking system (designed to track cold medicines containing pseudoephedrine precursors to curtail the illegal dual use of these medicines to create recreational drugs), one could automate tracking sales, increasing the efficiency of data sharing in a consistent format. There are, of course, some thorny issues that would have to be navigated. Data would have to be completely de-identified to protect health privacy, as mandated by law in the United States and other places. Large retailers like Target, Tesco, or 7-Eleven would have to be included, but systems would also have to be engineered to protect their proprietary sales data—from that of their competitors. Online retailers pose an interesting predicament related to the desired geographic specificities, but given their market size, they must also somehow be included in this approach. Managing, storing, and analyzing the data would also be a challenge.

But with data from multiple sources capturing anything an individual could purchase anywhere, local public health departments could have an additional tool to fight an emerging epidemic.

As a graduate student studying public health and business in a digital age, I am stunned that we have not done this already. Obviously, the world has come a long way since John Snow's first epidemiological investigation in the mid-1800s, but the world of digital syndromic surveillance is far from being complete. Let's start somewhere.