Chipo Moyo (not her real name) was ready to give birth. Over the past eight months she had followed all the advice of her midwife and was booked to deliver in a Harare clinic. But when she arrived, already in labor, the clinic doors were locked. Passersby explained that the nurses were on strike. As her contractions came more quickly, Chipo and her husband took public transport to a hospital where she finally delivered.

Similar chaos confronted women across the city. Naked women lay on the bare floor in one makeshift delivery room. Women moved from one health care center to another looking for someplace to deliver. Some women went to private hospitals where they had to pay very high prices for delivery.

Although governments may sign lofty declarations, they too often fail to put in place the practical strategies needed to follow through.

As that crisis grew late last year, I was attending a global summit called ICPD+25 in Nairobi. The summit’s goal was to galvanize support for universal access to the full range of sexual and reproductive health information, education and services—and to complete the unfinished business of the first International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), held 25 years earlier. I was there on behalf of the Women’s Action Group, an organization fighting for the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women in Zimbabwe. But as I listened to government leaders solemnly pledge their support to the ICPD Program of Action, text messages from home alerted me to the situation on the ground and highlighted one simple fact: words alone don’t save lives.

Although governments may sign lofty declarations, they too often fail to put in place the practical strategies needed to follow through. This is unacceptable.

To be sure, there has been significant progress in the past 25 years, and the summit catalogued the gains. For example, global maternal mortality rates have fallen by 38 percent and the number of skilled birth attendants increased by 80 percent. But, as also noted by experts attending the summit, this progress has been tragically uneven.

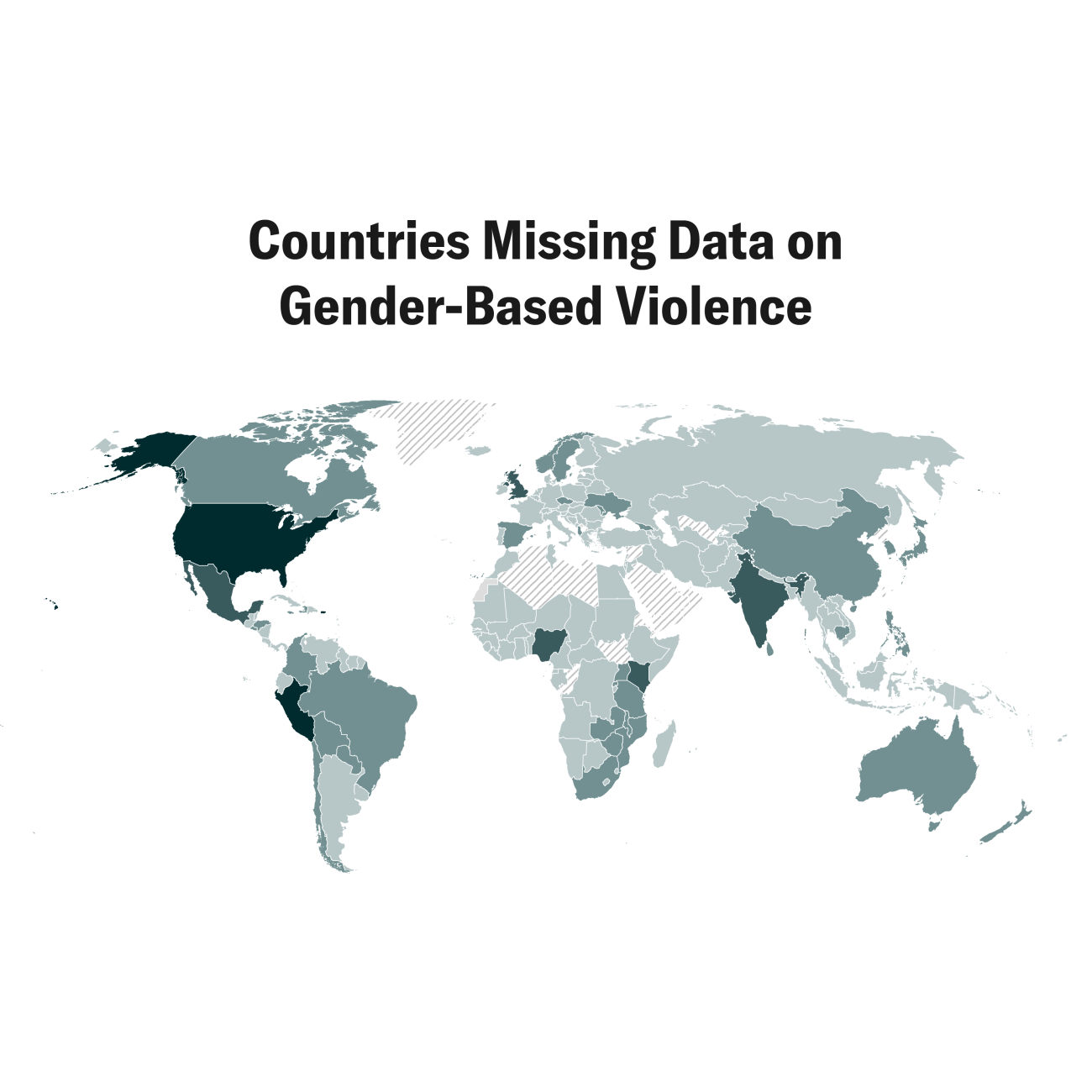

Consider the goal of zero preventable maternal deaths.. According to a UNICEF report, from 2000–2017, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia accounted for 86 per cent of maternal deaths worldwide. Sub-Saharan Africans suffer from the highest maternal mortality ratio, 533 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births—or 200,000 maternal deaths a year—more than double the global average.

Greater risk of a woman in a low-income country dying from a maternal-related cause than women in high-income countries

More needs to be done in Africa. The maternal mortality ratio is unacceptable, especially considering that almost all maternal deaths are preventable by having skilled, supervised health personnel—doctors, nurses, or midwives—attend births and by having the proper equipment and supplies available. The percentage of births attended by skilled health personnel varies greatly by global region. From 2012–2017, only 59 per cent of the births in sub-Saharan Africa were attended by skilled health personnel. In other world regions, coverage ranged from 68–99 percent. In Zimbabwe, the government’s persistent failure to prioritize the training, pay and retention of skilled health personnel is largely to blame for the nurses’ two-month strike that left pregnant women to deliver at the hands of untrained traditional birth attendants.

Maternal mortality rates are also sensitive indicators of wealth inequality. The risk of a woman in a low-income country dying from a maternal-related cause is about 120 times greater than a woman living in a high-income country. And, most of the world’s lowest-income countries are in Africa, including Niger, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Sierra Leone.

The majority of the world’s countries, including my country Zimbabwe, left the ICPD+25 having committed to mobilize the required financing to finish the ICPD Program of Action. They committed to national budget allocations; gender budgeting and auditing; and exploring new, participatory and innovative financing instruments to ensure full, effective and accelerated implementation of the ICPD program.

Looking ahead to March 2020, governments will again gather, this time for the Commission on the Status of Women in New York. There, they will review the Beijing Platform for Action that was put in place 25 years ago to promote gender equity in health and 12 other crucial areas.

African countries must look closely at what it will take to save the lives of women and girls.

While such conferences can affirm global intention toward achieving gender equality, governments must realize that making a commitment and not following through is worse than not making a commitment at all—for such inaction fuels cynicism, distrust, and despair. African countries must look closely at what it will take to save the lives of women and girls. Rather than set priorities at the expense of women’s health, they must recognize that women’s health is central to a vibrant society and growing economy. But if history is any indication, governments won’t do it on their own. Civil society organizations must hold their governments accountable.

Africa needs trained personnel to attend to pregnant women. It’s that simple. Governments should start by allocating 15 percent of their national budgets to health—as they have also committed to do.