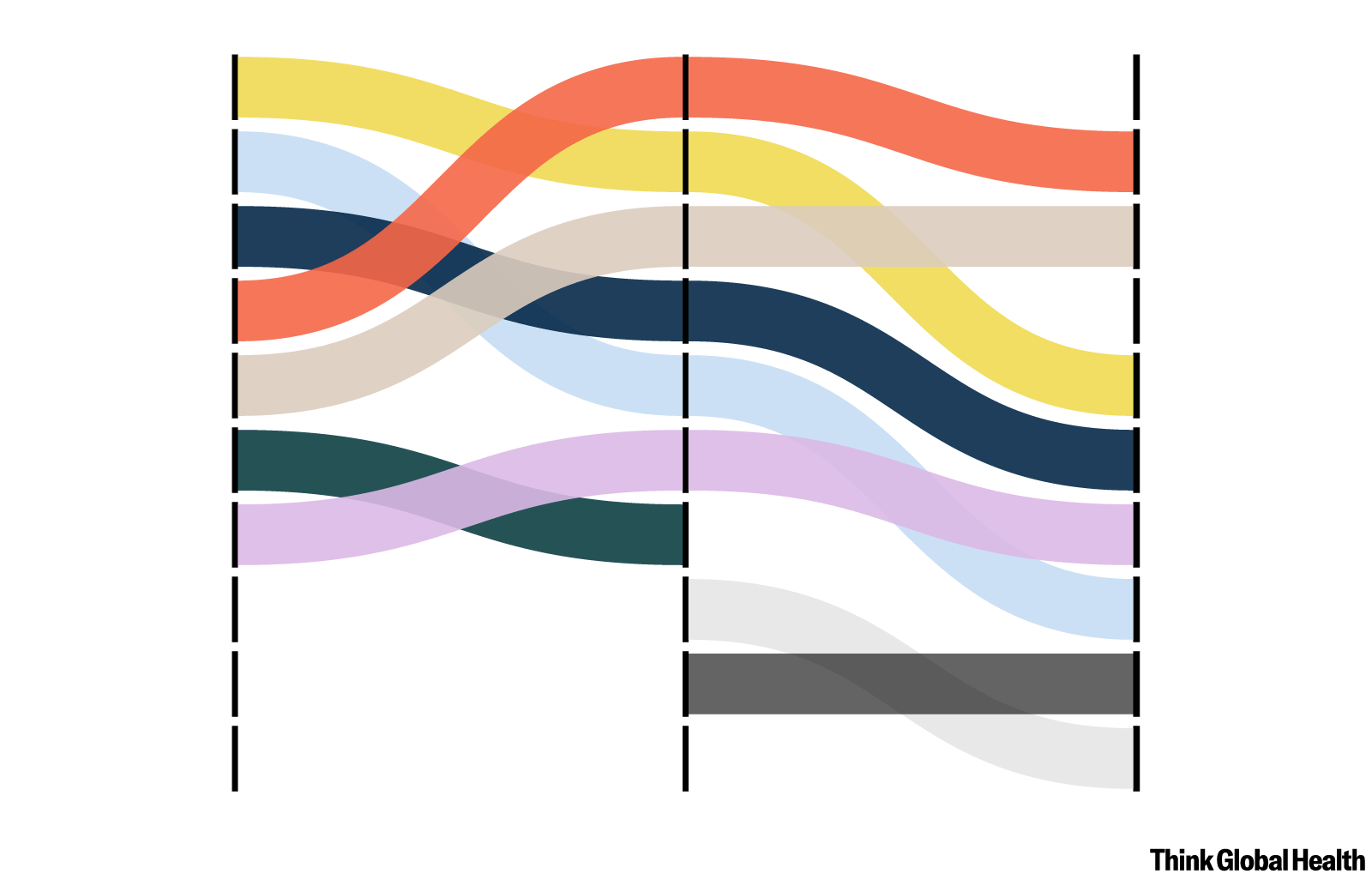

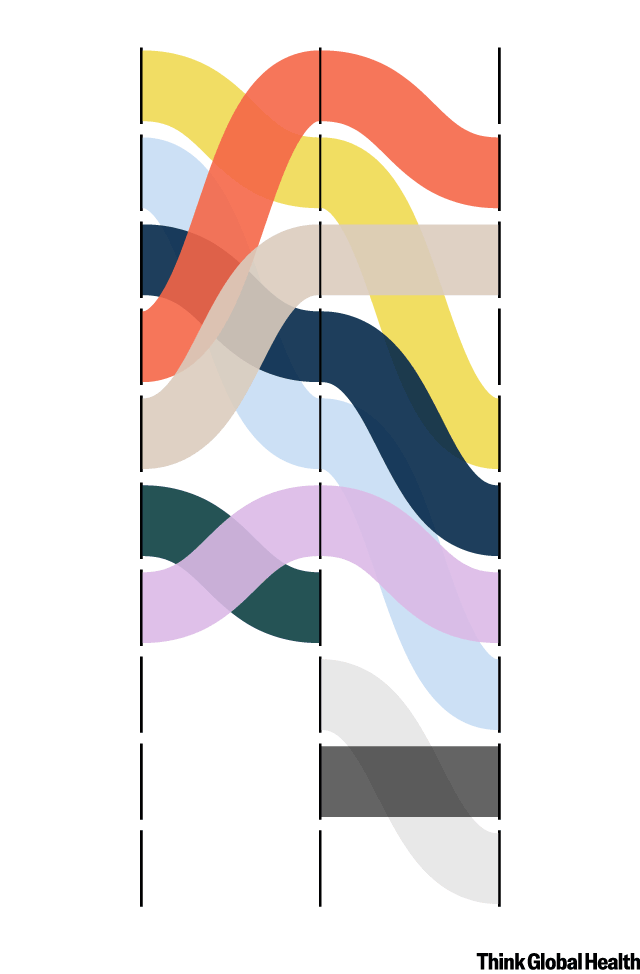

Around the world, countries are experiencing an epidemiological transition. Defined as the shift from infectious diseases—such as HIV and TB—to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs)—such as cancer and stroke—as the leading causes of death in a country, this broad evolution is driven by the availability of new treatments, economic development, and demographic changes over time.

When it was introduced in 1971, the theory of epidemiological transition was presented as a linear process, but experts now agree that social determinants of health—such as income, housing, and education—play a major role in shaping causes of death among and within countries. As a result, according to the latest iteration of the Global Burden of Disease Study, infectious diseases persist in poorer regions and heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) dominate the overall causes of death list.

Heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease dominate the overall causes of death list

"Something I always reflect on is how stable those conditions are in that ranking," says Liane Ong, lead research scientist at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and coauthor on the study. "And how unfortunate it is that many of these conditions don't need to be as high as they are."

As South Asia's largest country, India is the greatest contributor to the NCD burden in the region. Increasing gross domestic product (GDP), lifestyle changes, and an aging population have led to a rise in NCDs as the country's leading causes of death over once-pervasive infectious killers such as tuberculosis and diarrhea. In 2018, NCDs accounted for 63% of all deaths in India.

Worldwide, ischemic heart disease, stroke, and COPD have dominated IHME’s causes of death ranking for the past 30 years. Despite decades of high NCD prevalence and a greater share of the world's population is dying from NCDs, funding for prevention and management of these diseases is relatively low. According to the civil society organization NCD Alliance, just 1 to 2% of development assistance for health has been allocated to NCDs over the last two decades. Lack of action deepens existing inequities.

Compared with wealthier nations, low- and middle-income countries have mortality and morbidity due to NCDs, in part due to health systems that are ill equipped to address them. The World Economic Forum estimates that NCDs could cost India $3.55 trillion between 2012 and 2030 due to increased health-care spending and loss of economic output.

The COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted the need to strengthen India's health system. After a brutal surge in mortality in May 2021, COVID-19 topped the country's causes of death ranking, and those pandemic fatalities are likely much higher than reported. Researchers found that the country's high NCD burden was linked to the death spike, with people living with obesity and diabetes particularly more vulnerable to COVID-19.

"[COVID] was a big test for the whole world," says Mohsen Naghavi, the IHME study's lead author and director of Subnational Burden of Disease Estimation at IHME. "Some health systems completely failed."

Researchers argue that—in addition to greater investment in health-care access, prevention and treatment—more can be done at the individual level to stem the rise of NCDs.

"COVID taught us [the importance of] buy-in from the public,” says Ong. "Education is important not just for COVID, but for noncommunicable diseases as well—whether it is seeking medical care early or educating yourself about risk factors.”

Education is important not just for COVID, but for noncommunicable diseases as well

Liane Ong

Even though India introduced a National Programme for Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases in 2010 to address its large NCD burden through health promotion, prevention, and treatment, implementing the program across the country's states remains a challenge as health departments continue to deprioritize NCDs. A recent study conducted in urban informal settlements of Mumbai reveals a lack of streamlined care, affordability challenges, and little education on NCD prevention, screening, and adherence to treatment. The study recommends local support groups for patients to motivate patients to seek and maintain care.

"How can we decrease deaths and increase life expectancy?" asks Naghavi. "We should work more on NCDs."