Few research projects drive health policy across the world like the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

Compiled every few years by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the study has a straightforward but daunting objective: estimate both all the deaths and disabilities occurring worldwide and their causes.

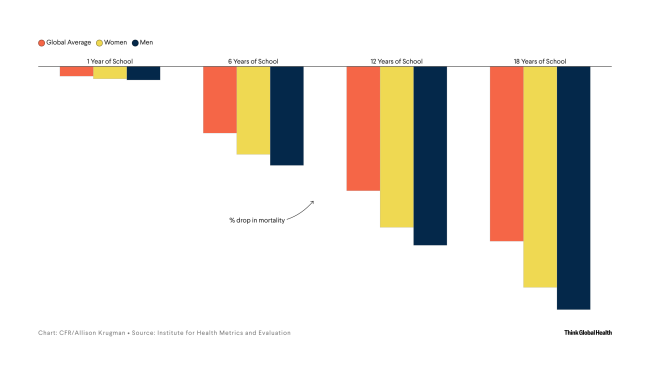

In the early 1990s, the study's first results helped inspire Bill Gates to get involved with global health. World leaders use the findings to gauge how cardiovascular disease, infectious pathogens, mental illness, and every other condition in existence affects everyday citizens. As the GBD susses data on deaths and disability, it also informs trends in topics such as gender and education.

The study's latest iteration—or cycle—began releasing results this spring via the IHME's website and The Lancet—and covers data stretching from 1950 to 2021. This cycle is special because it comes after a years-long hiatus as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thousands of international scientists contribute to the study, so one might assume the lockdowns had a stifling effect on collaboration.

Yet Christopher Murray, the founding director of IHME, says one of the biggest hurdles came from data being released too quickly. In an interview with Think Global Health, he recounts GBD's history and how the pandemic's hurdles were overcome.

Murray also explains how the GBD is adopting artificial intelligence tools, gives his take on major findings from this cycle, including how declining birth rates could influence economies for decades to come, and reveals what IHME does to celebrate once a GBD cycle is complete.

The conversation arrives alongside the capstone papers for this cycle—one offers a forecast for global life expectancy and the other covers global risk factors for poor health.

Fertility Rates Decline Worldwide

By 2100, fertility rates will not be high enough to sustain population growth in most of the world

Think Global Health: The Global Burden of Disease studies have been running for more than 30 years. What do you enjoy about conducting this study? What drives you and your colleagues?

Christopher Murray: What you enjoy and what drives you are often different, so I'll answer in order. What I enjoy is the deep-seated curiosity about what's happening in the world. Many of my colleagues are just endlessly fascinated about how the world surprises us and how our prior beliefs are often pretty wrong.

What drives us is the core belief that what we do gets used and is helpful for decision-makers. We just had a visitor—a Fulbright scholar from Tanzania—who said how pretty much every corner of Tanzania's government counts on the GBD for understanding health and making decisions. Real-world use of application is what drives us because we want to help people make evidence-informed decisions.

Think Global Health: Can you describe the origin of the GBD study? It began when you were working at the World Health Organization (WHO), correct?

Christopher Murray: We started the GBD because the World Bank was deciding to write its first ever policy report on health, which became the World Development Report 1993. They began the analytic work in 1991 and asked two simple questions: What are the most important causes of death in the world and what causes ill health the most?

The WHO couldn't answer in a coherent way because if you added up all the health claims at the time, the result would have meant that the world's population was dying three times over. A high-level comprehensive, internally consistent, comparable view of people's major health problems didn't exist.

Health problems that didn't have advocacy groups were, not surprisingly, the ones that disappeared from that discussion. In 1990, global advocacy for mental health was scant, so nobody paid much attention to mental health. No numbers had been determined, making it easy to ignore.

You manage what you measure—that's the adage from business. If you aren't measuring health, what are you managing? That's why we wanted a consistent, comparable approach that was evenhanded across diseases, enabling calculations of the relative magnitudes of risk factors.

Think Global Health: That World Bank report was pretty influential on Bill Gates in particular?

Christopher Murray: Bill tells the story that the report was really what got him interested in global health. It was the idea that inexpensive approaches to intervening in disease and saving lives, particularly for children, were possible but just weren't happening because people didn't have access to interventions or resources. For an exceedingly small cost, it was possible to make such a difference in people's lives. It got him hooked on global health and that's been consequential in terms of investments and innovation in global health.

Think Global Health: What are the major stages of setting the GBD study? How does the project get off the ground?

Christopher Murray: From 1991 to 1998, the effort was artisanal because the project involved such a small group of people. We tried to do the best we could with the available data.

When Gro Harlem Brundtland became director general of the WHO and decided to bring this approach into the organization, we became more engaged with countries, more ministries of health, and larger numbers of people. That was one critical juncture. When Brundtland decided [in 2002] to not run for a second term, the locus of work transitioned—it became shared between the WHO and other groups. I went back to Harvard, and we had a contingent there.

You manage what you measure…If you aren't measuring health, what are you managing?

The big change came when the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation was established in 2007. We radically overhauled the analytic approach. We adopted computationally intensive and more sophisticated Bayesian statistical methods. We were able to produce estimates with uncertainty, which we hadn't before. That transformation, which unfolded from about 2007 to 2012, was a pretty big change.

We also launched an open call for collaborators. Initially, we ended up with about 500 for GBD 2010. We've now hit the 12,000 mark. We've dedicated more resources to teams focused on math, science, algorithms, which are tailoring statistical and computational methods to do a better job.

Think Global Health: You're working with a variety of countries, which have different resource levels. What types of health surveys and data sources do you typically pull for the GBD study?

Christopher Murray: We have 317,000 data sources that went into GBD 2021. A data source could be a census; it could be a household survey; it could be the food balance sheets from the Food and Agriculture Organization. It could be biostatistics for a country for a year.

The tally now is 317,000 and keeping track of them is complicated. We give each data source a unique identifier—called an NID—that allows us to put every source used and the associated metadata in an external data catalog.

The NID allows us to trace where the data source has been used by different groups. The same survey that tells us about tobacco in Mozambique can also tell us about antenatal care.

The country with the most data sources is the United States—which has about 6,000. But the median number is 1,500 per country. The lowest is Tokelau, a territory in the Pacific—which provided about 350 data sources.

More data than people think is available, but the value is not so much the number. The big dividing line is whether a country or jurisdiction has complete vital statistics. The 100 countries that have complete or near complete vital statistics provide an annual or regular feed of who dies from what, aggregated by age and sex. It's super useful and powerful, and we can see really settled trends.

When countries don't have complete vital statistics, you infer the pattern of mortality from things such as verbal autopsy or disease-specific models. It's a much less robust way to understand health problems.

Think Global Health: How did the number of countries with complete vital statistics change during the pandemic years?

Christopher Murray: Despite investments into and broad recognition of the critical role of CRVS [civil registration and vital statistics], change hasn't been significant.

The two high points have been the progression in China, where more and more deaths are being captured by their routine systems, the ones overseen by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. India has also witnessed an expansion of CRVS, that in some states, such as Goa, are nearly complete.

Other states are steadily increasing their CRVS, but not enough for us to confidently distinguish the trends in the registered deaths from expanded coverage from what's actually happening in the population now. No progress of any real note has been made in sub-Saharan Africa.

Think Global Health: In what ways did COVID interrupt GBD activities, and how did you overcome those hurdles?

Christopher Murray: The pandemic interrupted the GBD in two dominant ways. First, as an organization, we pivoted about 100 people to work on COVID. We did a lot of COVID modeling, [and] a huge amount of COVID data work to make sense of messy data for hospitalization, cases, deaths, and seroprevalence. That was on a timeline with policy engagement with political leaders that took considerable effort.

From an analytic point of view, the GBD was also greatly delayed because we had to figure out who died at what age, everywhere. It's a comprehensive study. We had to also determine which other causes of death and illness were affected by behavioral changes during the pandemic.

Some child causes went down—measles, diphtheria, and some pneumonias. In adults, we saw a complicated pattern: in some countries heart disease and diabetes went up. We're trying to make sense of whether that was a coding error or ascertainment bias or was real.

Now we're planning GBD 2023, at the end of this year, to reflect what we've determined about how to make sense of the data that's coming in—though some COVID mysteries remain.

Think Global Health: What made the validation process so hard?

Christopher Murray: It has to do with the lags in the data. During COVID, many governments, but not all, had much more rapid reporting of data. They would report deaths from the day before or two days earlier. They would report hospitalizations and cases. That was fantastically useful, but also very messy because different standards were applied in different places.

As the pandemic continued, once testing became much more widely available, we started to get some really confusing signals in those quick reporting systems. In some countries, such as the United States, anybody who was hospitalized and COVID positive [as a COVID patient] was reported, not necessarily because they went to hospital because of COVID. This became a really big issue after omicron. Likewise on death certificates, they would assign a COVID death if the person died and had had COVID, as opposed to dying from COVID.

The early part of the pandemic was the reverse. When testing was very short, many people were underdiagnosed and more deaths were reported.

Now, in high-income and middle-income countries, all that eventually gets adjudicated: someone completes a full death certificate and lists all the intermediate and associated causes of death and that gets reviewed. We put in more stock as we look backward at a complete and careful death certificate. This explains why the numbers are different than many countries reported. In some cases, they're higher, in some cases lower.

Eventually, these AI tools can remove some of the drudgery and allow people to concentrate on the content they want to convey

Think Global Health: How do you manage and nurture relationships between thousands of collaborators?

Christopher Murray: The work is definitely labor and resource intensive, and we have a dedicated team to service the collaboration and the collaborators. You need to spend resources on people who can answer the collaborators' questions. We run webinars on various topics.

Then comes the process of management—enrolling people and having them agree to the study protocol, identifying their interests, and providing the material they want. Say they're interested in sickle cell anemia and live in Burkina Faso. [Then] they [will] get the relevant results to comment on. The paper-writing process involves thousands of people commenting on the draft.

Journals require every author, sometimes more than 2,000 for a single paper, to sign an author form. We have to collect those forms and send them to the journal. Every single person must sign and tick the boxes indicating what they contributed.

The logistics are huge. We're trying to use AI to make it easier.

Think Global Health: How are you using AI in that process?

Christopher Murray: We're trying to use LLMs [large language models] in a number of ways. The first is long appendices for the capstone papers—thousands of pages of detail on methods and results.

We feed this information into an LLM and create a platform that enables asking a question in plain language, such as "what were the specific corrections done for a report of height and weight in these countries?" It'll tell you. That's pretty neat because then you don't need to dig through thousands of documents; you'll get an informed text response.

Another application can read all the comments from collaborators that need to go to the lead author—about the methods or discussion sections. The AI program can do that pretty well.

We're just at the beginning. Eventually, these AI tools can remove some of the drudgery and allow people to concentrate on the content they want to convey.

Think Global Health: You mentioned the story about Bill Gates. What are some other examples of how policymakers have used the GBD study to enact change?

Christopher Murray: One I like is that the president of Botswana used the GBD's alcohol attributable burden in Botswana to persuade the legislature to pass alcohol taxes and regulations. There had been an issue about a loophole that meant small quantities of alcohol were not being taxed, and therefore children were buying it.

We find many examples of the findings on risk-attributed burden being used to argue for government-funded interventions, including improved cookstoves in Rwanda to reduce household air pollution.

We saw many countries take their burden of disease results to establish policies on mental health. In some countries, they made institutes for mental health to develop solutions.

Think Global Health: This cycle's life expectancy report had a number of takeaways. One was that child mortality rates declined during the pandemic, continuing long-standing progress with pediatric well-being. Did you did you find that surprising?

Christopher Murray: We didn't find it surprising after the first six months of the pandemic, when the data made it clear that COVID-19 had very little impact on children's physical health.

It's a huge blessing that COVID wasn't really killing many children.

Then we started to see, during that first winter [of 2020–2021], that the behaviors people were adopting—mask wearing, social distancing—were reducing cases of flu, RSV [respiratory syncytial virus], diphtheria, measles in all age groups, but particularly in children. In the Northern Hemisphere's summer of 2020, some were concerned that childhood vaccinations dropped because of less outreach: They expected to see a bump in childhood mortality.

Thankfully, that did not occur.

Think Global Health: GBD 2021 released a paper on fertility that predicts a massive shift in birth rates, namely, from high-income countries to low-income countries. Fertility rates will not be high enough to sustain population growth over time in 97% of the world's countries and territories. How should policymakers plan for this future?

Christopher Murray: People hugely underestimate the power of demography to change things.

In many countries, unless you welcome migrants aggressively, you end up with inverted population pyramids. Instead of the classic population pyramid, in which the largest age group is children and groups get smaller as people age, it's the reverse. The inverted pyramid has more people age 80 than newborns.

That's hard for governments to sustain—think of health insurance and social security. It's hard for economies because 20-year olds, 30-year-olds, 40-year-olds are the ones who buy houses, cars, and material goods.

When populations are not only inverted but also shrinking, then construction becomes a real issue because it is a big driver of many economies. Knock-on effects are numerous.

Then there's the geopolitics. If you're China and your population is going to drop 70% this century, it's hard to imagine that you'll still have the same geopolitical clout. China will also face fiscal and social structural challenges.

People hugely underestimate the power of demography to change things

In contrast, Nigeria is going to keep growing well into this century. It's hard to imagine that it won't become a much larger global player.

In a world in which many countries are desperate for migrants to keep their economies going, the situation will become more desperate over time. Many countries in Africa will be the only places in the world that may have high enough fertility that people can leave if they want to and that doesn't have a big repercussion on their home economies. This situation applies largely to West Africa, but not exclusively.

For a generation, or maybe two, you can manage this low fertility problem by bringing in migrants, but some countries don't want migrants right now or have been resistant. Russia and Japan are examples. Japan is bringing in people for shorter periods but is really struggling.

Think Global Health: Now that the GBD capstone studies about forecasting and risk factors have been released, how do you plan to celebrate?

Christopher Murray: I'm very happy that it's out because it was so challenging to get done because of COVID. We have this funny, weird tradition involving a bell from a big ship. When a GBD cycle finishes, we get everybody together and ring the bell.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.