The fast-growing Hughes Fire is the latest in a string of blazes that have ravaged Southern California this month. Fueled by dry conditions and strong winds, the new fire erupted as the Palisades and Eaton fires—which have killed 28 people and destroyed 14,000 buildings since January 7, 2025—continue to burn.

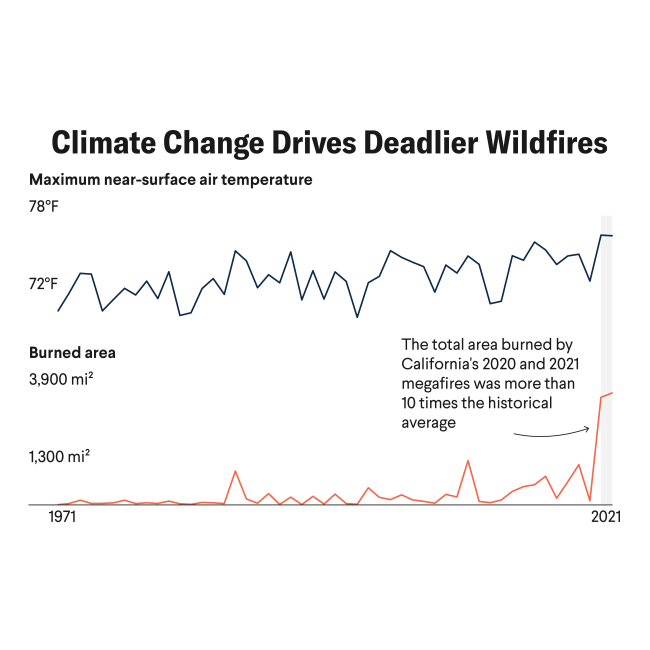

The devastation in California has once again drawn attention to the increasing frequency and intensity of wildfires throughout a fire season that continues to lengthen, especially in western North America. Those trends are expected to worsen over time in response to climate change.

Lasting Damage to Health

Research has demonstrated that, in addition to massive devastation and direct loss of life, smoke from wildfires presents a risk to population health far beyond the immediate area of fire impact. As many as 1.59 million deaths per year globally have been attributed to smoke from landscape fires and its impacts on respiratory disease, heart attacks and stroke, exacerbation of type 2 diabetes, and dementia.

Although public health agencies and communities have made great progress in developing communication, guidance, and prevention strategies to reduce the health risk that wildfire smoke poses, those strategies should be continuously updated to account for new information about both health and environmental risks.

In particular, within the past decade, a new and troubling additional health risk has emerged, when fires burn entire communities, incinerating homes, commercial buildings, cars, and numerous manufactured products and materials. These large structural fires not only present new health risks but also require postfire environmental sampling as well as complex cleanup, disposal, and restoration efforts, all of which increase costs and extend the period of community disruption.

The devastation in California has once again drawn attention to the increasing frequency and intensity of wildfires

In the case of the Southern California fires, smoke produced during the acute phases of a fire event is less of a health concern because populations in the immediate proximity to the fires evacuate and high winds disperse smoke toward the ocean. However, high levels of some heavy metals, including lead, have been measured downwind of fires, including the Camp Fire in Paradise, California in 2018.

Early results show a similar pattern in the Los Angeles fires, with airborne lead concentrations rising well above normal levels. As large structural fires become more common, new hazards have emerged, including deposits of persistent pollutants such as heavy metals in soil and groundwater; exposure to flame retardants; inhalation of asbestos and other contaminants during cleanup, demolition, and reentry; and the presence of hydrocarbons and metals in drinking water.

The Los Angeles fires are the most recent example, but others also come to mind, including recent ones in California, Colorado, Hawaii, and Canada. As these events become more common, the need increases to better understand the potential health risks and to develop guidance for first responders, the public, and those involved in cleanup and rebuilding.

Lessons from Other Wildfire Cleanups

For first responders and those exposed to persistent smoke, the masks or air cleaners that typically protect from the particulate matter (PM2.5)—the most hazardous component of burning vegetation—do not protect against highly irritating gases produced when plastics common in most modern homes burn. First responders and outdoor workers are particularly vulnerable, but residents or contractors reentering fire-damaged areas or people living close to destroyed structures should also be aware of potential risks, especially deposits of ash on surfaces and the soil. Just this week, the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department warned its personnel to wear masks and decontaminate their uniforms before returning to their homes given concerns regarding asbestos and lead exposure from smoke and debris.

At present, specific regulations regarding fire safety, environmental preservation, and public health are atypical and responsibilities often unclear. More public health agencies are issuing guidelines for those returning to contaminated areas, and extensive cleanup and disposal activities along with drinking water restrictions are becoming the norm.

The risks associated with each fire vary depending on the intensity of the fire; the number, ages, and types of structures and materials burned; and the characteristics of the soil and water sources. Following the Fort McMurray fire in Alberta, Canada, for example, elevated levels of dioxins and furans, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, mercury, arsenic, and other metals were measured in ash samples, most of the arsenic originating from treated wood.

The contaminant levels in ash initially precluded residents from returning to homes in several neighborhoods. To permit them to do so, several inches of topsoil were removed from areas with burned structures and taken to a landfill. Fourteen months after the fire, contaminant levels in house dust were lower than those in control area homes.

Following the Camp Fire, state agencies and contractors undertook an extensive and lengthy cleanup operation, including removal of large amounts of debris and soil as contaminated waste.

The Camp Fire also led to long-lasting elevated levels of contaminants in drinking water. During the fire, water system pressure dropped because of firefighting and broken pipes. Intense heat likely led to degradation of plastic water pipes and contaminants pulled into water lines with the loss of pressure. Water samples collected after the fire had elevated levels of volatile organic compounds that exceeded regulatory levels in some cases, and water advisories remained in place for almost two years.

Studies of health impacts following these fires are rare, but will likely become more common

Following the Lahaina fires in Maui, Hawaii, in 2023, an extensive water quality testing and water distribution system repair and replacement program was put in place. All drinking water advisories were lifted roughly a year later.

Depending on local circumstances, contaminants could also enter groundwater or water used for agriculture, contaminating food supplies. Fire retardants dropped from the air are increasingly used in heavily populated areas. Ammonium phosphate fertilizer, the main ingredient in these retardants, irritates the skin and mucous membranes when in direct contact, but is otherwise not known to have long-term human health impacts. Recent research, however, has identified a number of metals—including arsenic, chromium, and lead—in approved flame retardants that could contribute to elevated metal levels found in soil and on surfaces postfire.

Studies of health impacts following these fires are rare, but will likely become more common. A study in Canada measured increased risks of lung and brain cancers in people living in proximity to wildfires, but did not differentiate between exposure to burning of vegetation and manufactured materials. Another study of residents in homes not destroyed but adjacent to the Marshall fire in Colorado in 2022 reported increases in itchy or watery eyes, headaches, cough, sneezing, and sore throats one year postfire. Reports of symptoms were more common for those whose homes were damaged by smoke or ash.

Given that events such as the Los Angeles fires will occur with increasing frequency, the need for effective regulations and continued development of evidence-based guidelines for cleanup and prevention is more relevant than ever to protect environmental and human health.