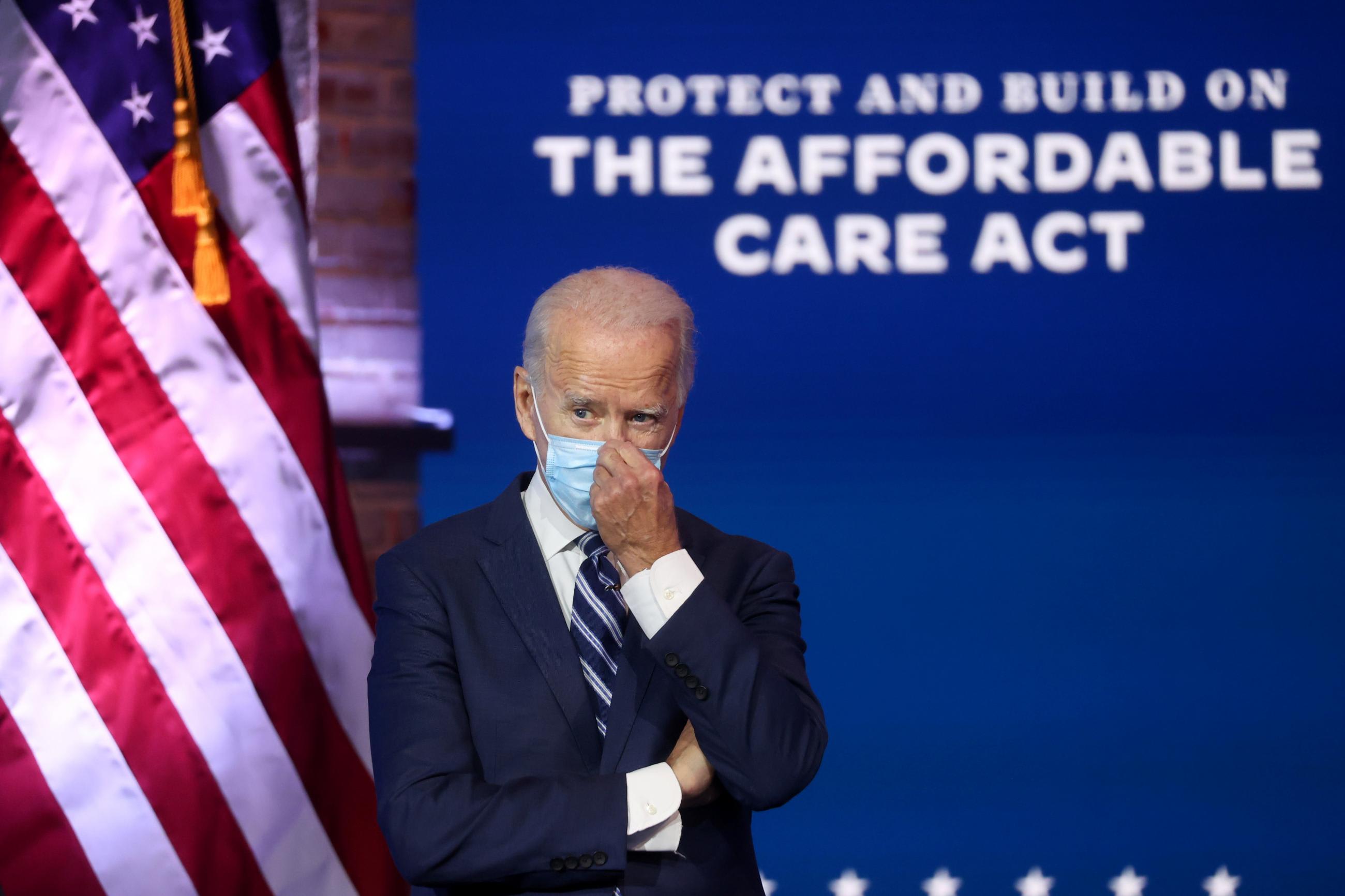

Elected but not yet in office, Joseph R. Biden is already strategizing how to best fulfill his campaign promises, one of the most prominent being health-care reform. During the campaign he pledged to expand health coverage, building on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that extended health-care coverage to over thirty million Americans and was thus a significant step towards universal health coverage.

President-Elect Biden's strategy to achieving universal health coverage, or "health care as a right," is to offer government-funded health insurance for anyone who does not qualify for Medicare and Medicaid, commonly referred to as "the public option." While this would not achieve truly universal health coverage, due to the lack of a mandate, it is another significant step towards it, and consistent with how many countries attained universal health coverage through slow and incremental policy reforms

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended health-care coverage to over 30 million Americans

Biden must also confront how he will enact such change. Whereas President Obama benefited from a unified government in 2010 when he passed the ACA, President-Elect Biden may not: the balance of the U.S. Senate will not be decided until runoffs in Georgia in January. So the Biden administration should prepare for the possibility of working with a divided government, with implications for his legislative agenda.

Nevertheless, the diversity of overseas approaches to universal health coverage offers important lessons to Democratic policy makers looking to dramatically expand U.S. health coverage. Globally, universal health coverage has taken many forms, with varied public roles, including:

- Socialized medicine, where the government owns and operates all hospitals, providing free care (as in the United Kingdom's National Health Service);

- Single-payer systems, where the government is the only insurer but hospitals may be owned privately (as in Canada). In such cases, there may be two tiers, where citizens have the choice of parallel private insurers; and

- Insurance mandates, where citizens may be legally obligated to purchase either private or public healthcare (as in Switzerland).

The United States is currently the only developed country without some type of universal health coverage. If it were to join its peers in realizing this feat, it would be the first country to make the switch in the last twenty-five years. The last country to achieve universal health care was Israel, passing a national health insurance law in 1995. The United States is more than a little late to this game, but three democracies' experiences with transitioning to and implementing universal health coverage may prove useful for the incoming Biden administration as it considers health-care reform.

Countries that implemented policies for UHC

Number of countries, by decade

Countries that implemented policies for UHC

By decade of implementation

Switzerland (1994)

In the nineteenth century, Swiss public health policy was almost exclusively managed at the canton or municipal level, with the federal government playing little role in citizens' health care. This changed in 1890, around a hundred years before the current policy was enacted, when the federal government was formally given a mandate to legislate on sickness and accident insurance. In 1899, it attempted to introduce a system of national health insurance. Its proposal, passed in 1911, established a regulatory framework for non-profit health insurance and supported health insurance funds with federal subsidies. These funds were precursors of institutionalized insurance—they were financial institutions that extended a package of benefits to members who bought into them. Cantons then declared whether buying into a fund was mandatory or voluntary.

In the nineteenth century, Swiss public health policy was almost exclusively managed at the canton or municipal level

Almost immediately, the funds grappled with low demand and disfunction. They were also criticized for charging individuals with preexisting conditions higher premiums; as a group, women paid higher rates, defined as having the preexisting condition of living longer. As health expenditures continued to rise, several efforts were made at reform, but all failed to pass referendum. Swiss leadership at the federal level proposed reforms, including compulsory insurance and standardized premiums, several times from 1964 through 1987. Proposals faced strong opposition and failure in the legislature. It was only in 1994, a century after the federal government was given authority to legislate on health insurance, that reforms related to compulsory insurance passed referendum.

The Swiss reforms were neither groundbreaking nor revolutionary. They entailed limited federal government involvement, unlike a single-payer or national health system. Insurance companies remained privately owned. Yet the reforms were a long and arduous process.

Israel (1995)

Much as in Switzerland, Israel's health coverage system originated as non-profit health insurance funds established between 1920 and 1940. Originally, enrollment was voluntary. However, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, the resources of the health-care system became strained, especially as the population aged.

Seven years later in 1995, in accordance with the recommendations of this report, the National Health Insurance law came into force, mandating UHC

To resolve their health-care issues, the Israelis looked to the executive. As the gap between the demand for health care and the system's resources widened, the Cabinet of Israel established a State Commission of Inquiry in 1988 with the purpose of examining the functioning and efficiency of the public health system.

Seven years later in 1995, in accordance with the recommendations of this report, the National Health Insurance law came into force, mandating universal insurance coverage. The insurers are competitive, non-profit-making health plans, operated through public funding, that function much as managed care organization does in the United States. Individuals are free to choose any of the four plans.

In the case of Israel, decisive action by the executive cut short the long process taken by the legislature in Switzerland. An insurance mandate was quickly and effectively implemented.

Canada (1966)

Until the early twentieth century, health-care legislation was primarily within the domain of the Canadian provinces. Canadians first discussed universal health care in 1919. However, it was not until 1945 that the federal government attempted to legislate on health insurance, prompted by the Great Depression and World Wars.

Canadian provinces rejected federal legislation on universal health coverage in the '40s as an incursion into provincial jurisdiction. In 1947, the first Canadian province, Saskatchewan, implemented nearly universal health care, followed by British Columbia and Alberta. These provinces pushed the federal government to fund this coverage. Despite strong opposition to public funded care from doctors, the Canadian Medical Association, insurance companies, and big businesses, a fully universal hospital insurance program was founded in 1958. In 1962, Saskatchewan brought doctors' services under its coverage, a move that was followed by all provinces within six years. In 1966, the federal government passed an act partially funding hospitals and medical insurance for all provinces.

As with Switzerland, Canada took many decades to make federal universal health coverage a reality. Where Israel was pushed by its executive, Canada was pushed by its provinces as well as by an exogenous shock to the health system—an economic depression and wars—which laid bare the capacity and cost issues of the prevailing situation.

Under the United States' current system, 29.8 million individuals are uninsured

Though each of these three countries pursued different means of achieving universal health coverage, two things are certain across all of them. First, the transition to universal health coverage takes time—a lot of time—from the first conversations to full implementation. Second, there is no single path to achieving universal health coverage.

Both of these truths offer hope for a Biden-administration that may face significant legislative roadblocks. The United States has already started questioning the limitations of its current system, under which 29.8 million individuals are left uninsured, a number that exceeds the population of Australia. These countries' experiences also show that shocks to the health system such as world catastrophes and global recessions—not unlike those caused by the COVID-19 pandemic—may speed up the process.

President-Elect Joe Biden is intent on ensuring every American has access to affordable health care insurance. Judging by the trajectories of countries that have made this transition, the time is ripe for the United States to begin the transition.