I remember playing hide-and-seek when I was a young child, crouching under the suits and on top of my father’s shoes in the corner of a musty closet. I was delighted in not being found, but crouching in the confined space got old fast. What a relief to hear the yell of the seeker’s surrender, indicating it was safe to come out.

For many people around the country and around the world, the apartments or homes where we are sheltering have begun to feel like that cramped closet. We begin to imagine a call of all-clear, when we can uncurl ourselves and stretch out into the comfortable world we left behind.

But until we develop a vaccine against COVID-19, we won’t be able to return to the way things used to be. As long as most people lack immunity, resuming our normal activities will bring infections roaring back. When we do finally step back outside, it will have to be a gradual return guided by a concrete plan based on solid science. We need to act right now to put those plans in place and make sure that when that day comes, it arrives as soon and as safely as possible.

The measures we’ve taken so far won’t protect us from the virus; they only buy time

With remarkable speed, people have come to understand how physical distancing can “flatten the curve,” curbing the explosive spread of the virus and preventing our health systems from becoming overwhelmed. But the second part of the equation has been lost on many. The measures we’ve taken so far won’t protect us from the virus; they only buy time—time to prepare for the next phase of our response. It is crucially important we use this time well.

Three Actions We Need to Take Now

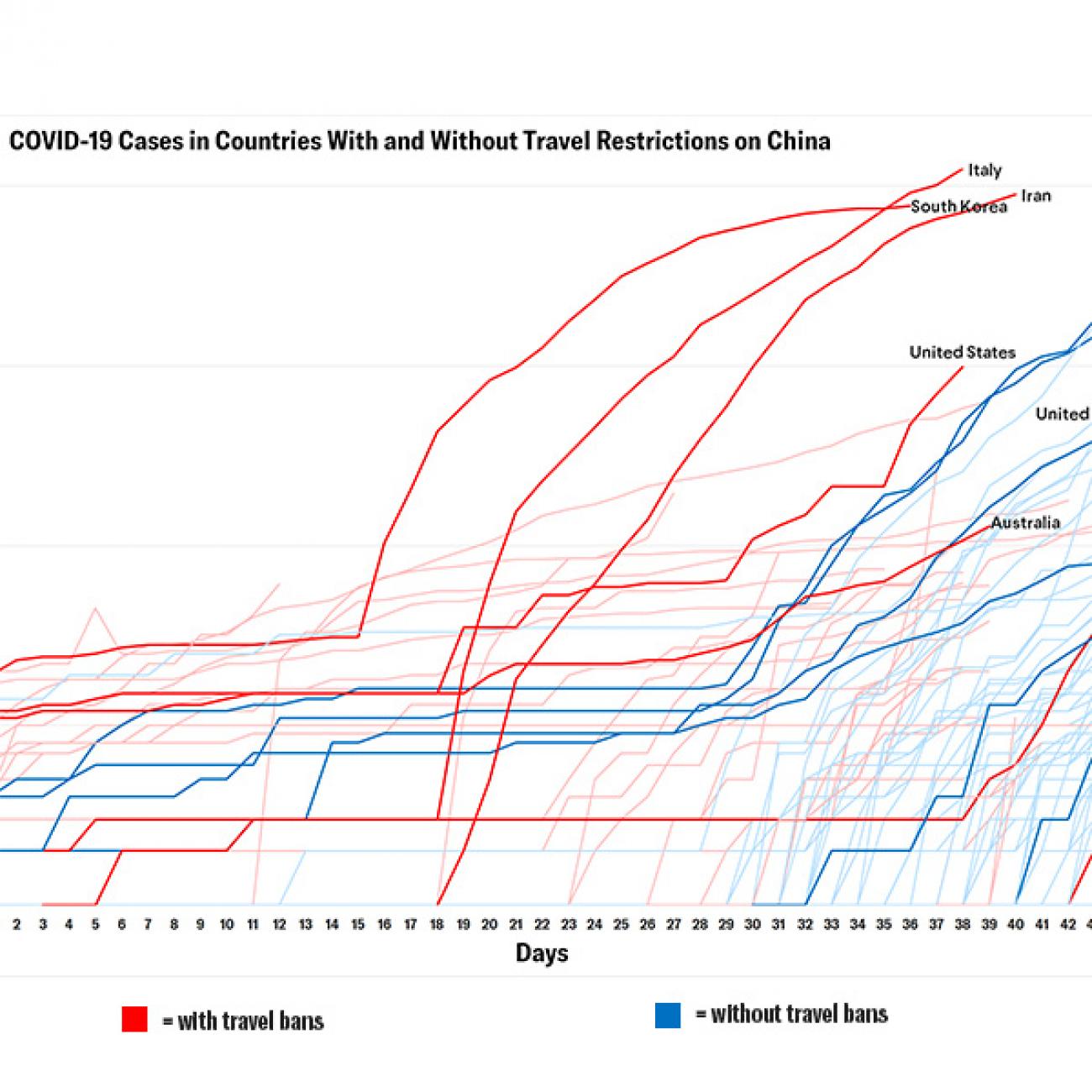

The first phase in a pandemic response is containment. In that phase, testing and contact-tracing can find people with infections and stop them from spreading the virus, with the goal of preventing a large increase in cases.

When we begin to emerge from our shelters, there will be fewer cases, but we’ll need to respond to them rapidly

For areas with widespread transmission, the pandemic response shifts to a phase of mitigation—where we are now in much of the United States. In this phase, we undertake physical distancing measures to limit the number of people infected and reduce the strain on the health care system. There are early signs that the measures we’ve taken are working, slowing spread of the virus. But a second, crucially important and now well understood reason for sheltering in place is to have time to prepare for the next phase of pandemic response, which we call suppression. When we begin to emerge from our shelters, there will be fewer cases, but we’ll need to respond to them rapidly. The smarter and swifter we prepare for suppressing COVID-19, the sooner we can go out again and the safer we will be when we do.

There are three actions we need to take right now, and we need to meet specific measurable benchmarks in each before we resume normal activity.

First, we need strategic intelligence—sophisticated systems to track the virus and our response to it. We have to be confident that the number of new cases is shrinking, health care workers are safer, and cases still occurring are increasingly tracked back to their source. Communities will need resources and consistent protocols to track symptoms, cases, and deaths in an accurate, timely, and comprehensive manner, which we are far from achieving.

Second, we must fortify our hospitals and the entire health care system. Our hospitals need to be physically redesigned to safely screen large numbers of patients and staffed to provide critical care to at least double the number of people for whom they currently have capacity. We also have to ensure they have sufficient personal protective equipment and implement policies to minimize risk for our doctors, nurses, and all health staff. Singapore shows this is possible: it has had more than a thousand cases but, at least so far, not a single health care worker infection.

Singapore has had more than a thousand COVID-19 cases—but so far not a single health care worker infection

Third, we must revolutionize our public health system. To suppress any clusters of cases, we’ll need to promptly identify every new case and trace nearly all their contacts, isolate the ill and quarantine people who have been exposed. South Korea is exemplary of this, pioneering drive-through testing facilities, among other innovations, which have allowed them to test a higher share of their population more quickly than nearly any other country. South Korea recorded their first case on the same day as the U.S., and then faced an explosive outbreak in a religious community. As of today, their per capita death rate is one seventh that of the United States.

I am a tuberculosis specialist by training, and we do a lot of contact tracing, which is the bread and butter of public health. But for COVID-19, we’ll need an army of people to do it. By the time Wuhan got their epidemic under control, that one city had 1,800 teams, each with 5 people, tracing tens of thousands of contacts per day. The equivalent would be 300,000 people in the United States, well trained, equipped, supervised and with a wide array of social supports to offer cases and contacts and stop chains of transmission.

How well and how quickly we achieve all these goals will determine how soon and how safely we can come out

We will also need to establish new, voluntary facilities for patients who aren’t sick enough to require a hospital but who can’t be safely cared for at home. And our public health leaders must demonstrate that when they recommend changes in physical distancing, people respond by actually changing their behavior. How well and how quickly we achieve all these goals will determine how soon and how safely we can come out. And we must pursue them with discipline, meeting specific criteria such as those my colleagues and I at Resolve to Save Lives have summarized here. Only when all of the above pieces are in place can we begin to relax physical distancing.

And whenever that is, we need to loosen the faucet gradually rather than throw open the floodgates all at once and risk an explosion of new cases. Gatherings should be capped at 10 people at first, and restaurants will need to adopt physical distancing measures to welcome patrons. Schools and businesses may need to stagger their reopening, with new safeguards such as temperature checks and hand sanitizer at every entrance. Informed by data on spread, people traveling from high-prevalence areas will have to quarantine. Medically vulnerable people will need to be shielded even longer.

As months go by with no significant increase in cases, we can loosen certain measures further. We’ll monitor for new cases vigilantly, ready to tighten the faucet by returning to physical distancing if they spike. Policymakers should establish clear guidance for communities to follow during this progression, improving on the one we have suggested, so their residents will understand and embrace a process that will take months.

It’s tempting to wonder when things will return to normal, but the fact is that they won’t — not the old normal anyway. But we can achieve a new kind of normalcy, even if this brave new world differs in fundamental ways.

We may adopt new ways of meeting with colleagues and mingling with friends. Travel will require more forethought.

We will need to wash our hands more often, cover our coughs more carefully, greet and interact with one another differently. We may adopt new ways of meeting with colleagues and mingling with friends. Travel will require more forethought. Instead of the famous quarantina — the forty days that Venetian traders kept ships at anchor before allowing them to dock — we may grow accustomed to either carrying proof of immunity or spending fourteen days in isolation before entering a new country.

Governments that show they can adopt these measures will curb outbreaks without ordering their people back to shelter. Places that can’t will see their economies grind to a halt and find themselves isolated from the rest of the world.

There are silver linings. As we refashion our hospitals to address COVID-19, we will make them safer for patients with other afflictions as well. Health care associated infections are currently one of the leading causes of death in the United States, and new policies and better designs can reduce those numbers. Investments that rejuvenate our public health system will protect us from many infectious and other threats to our health.

Until every country has the capacity to curb this epidemic, none of us will be safe

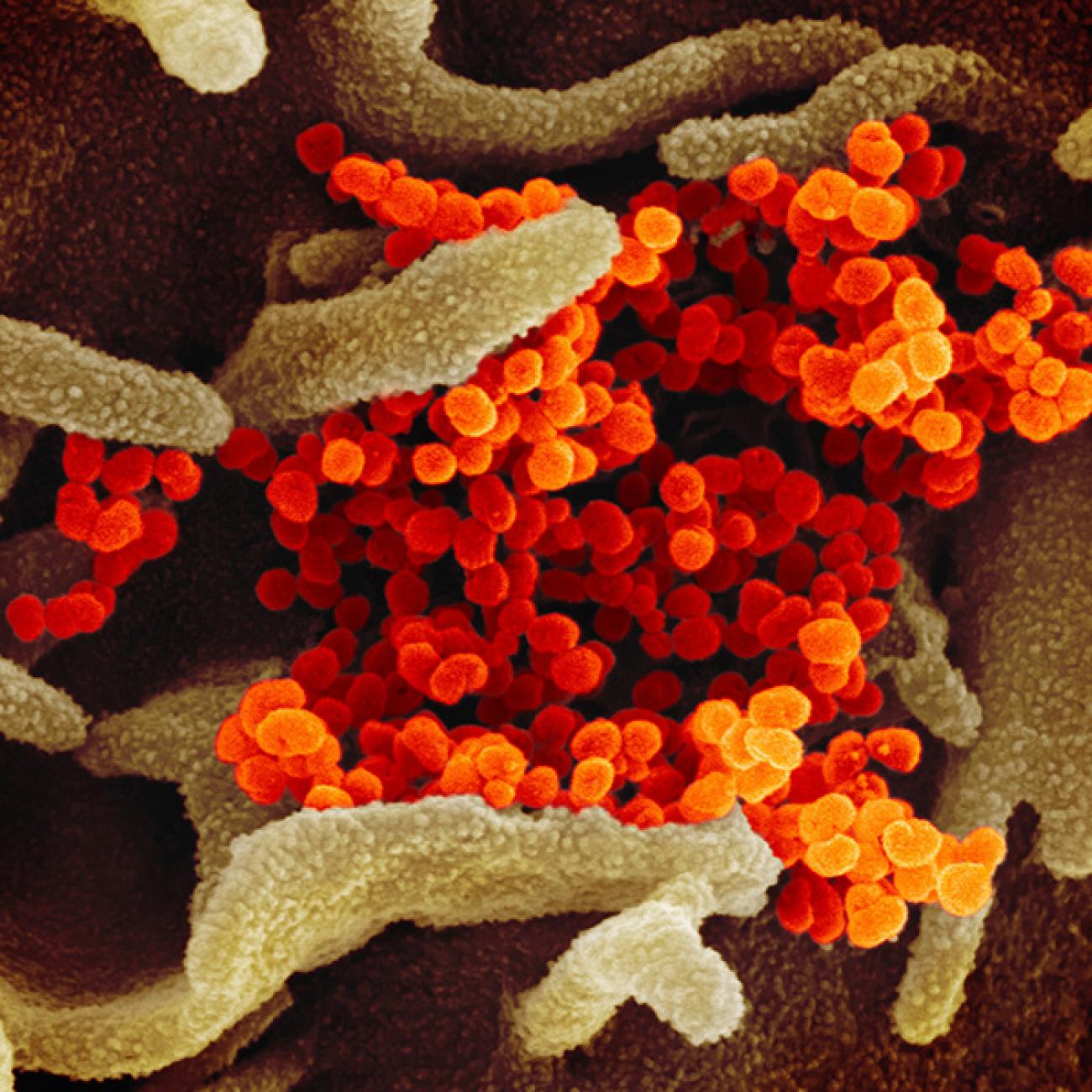

And by necessity, we’ll come to see more clearly that we’re all in the same boat. When it comes to infectious disease, the global community is only as strong as our weakest link: until every country has the capacity to curb this epidemic, none of us will be safe. We have to unite to fight this as a world war that it is, not states against one another but as people against microbes. In this fight, there will be no truce and no time-outs.

But with the right strategy and strong execution, we will be able to come out again to a safer, more united world, even if we’re not as free of infection risk as we were before.