As emergency physicians, we're trained to recognize a crisis. Over the past three years, we've watched as the COVID-19 pandemic battered our health-care system. As we limp into the winter, overlapping waves of influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and COVID-19 are putting more pressure on hospitals already buckling under the load. At the same time, burnout, and resignations among health-care providers have left fewer providers to care for the growing number of patients. As ER doctors we can tell you with certainty: this is an emergency. In too many ERs around the country, we don't have enough staff nor enough space to safely manage so many sick patients.

Conditions are akin to "no fall" zones, which in mountaineering describes terrain so dangerous even the smallest misstep can lead to catastrophe

These conditions are akin to "no fall" zones, which in the mountaineering world describes terrain so dangerous that the smallest misstep can lead to irreversible and catastrophic consequences. When roped together with other climbers, one mountaineer's fall can bring the whole group down. Falling is simply not an option.

For our colleagues, this winter feels like the "no fall zone" of emergency medicine in the United States. The mounting expectation to effectively evaluate and manage the highest levels of severe illness is compounded by unacceptably high patient loads for nurses and prolonged patient boarding in the ER—factors known to increase medical errors.

The "trickle down" shortages of staff and space at inpatient facilities have snowballed into an avalanche in the emergency department. Many hospital wards across the country are currently at or near capacity. When there's no more room on inpatient floors, patients stack up in the emergency department. When intensive care units fill and can't accept new admissions, the sickest patients do not miraculously get better and go home. The duty of care is left to emergency physicians. When we run out of gurneys, we find chairs in hallways. When we run out of chairs, we treat patients in the waiting room. When we're short of physicians and nurses, those of us remaining soldier on, shouldering the accumulating burden of risk.

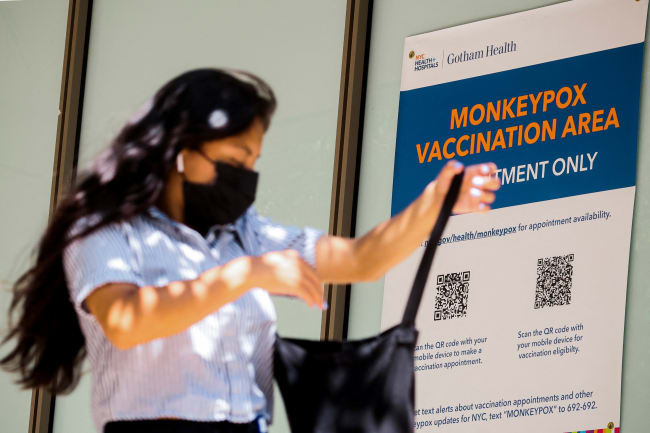

Such circumstances imperil not only patient safety but potentially national biosecurity as well. Emergency departments are the frontline for identifying and isolating emerging outbreaks. Recently, when Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) was spreading in Uganda, emergency departments in the U.S. were advised by local health departments to maintain a "high index of suspicion" for EVD and screen any patient presenting with fever and significant travel history.

In densely populated cities and international travel hubs, how reliably can emergency physicians maintain a high index of suspicion at the height of the influenza and holiday travel seasons, especially if we only have a few minutes with each patient and are forced to treat them in hallways? As the number of patients expands and the number of providers shrinks, the potential for missing a case only increases. One misstep would entail catastrophic consequences.

Similarly, a recent surge in group A Streptococcus (GAS) cases—caused by a potentially severe bacterial infection—has alarming implications. Earlier this month, the World Health Organization warned about the escalating rate of invasive GAS across multiple regions. In the United Kingdom alone, dozens of children have died since September 2022.

A century ago, over a quarter of children in many U.S. cities died before their first birthday. Thankfully, losing a child is something most parents and providers never have to experience anymore. While mortality from GAS remains rare, any preventable death in children is a tragedy.

We never refuse patients. When we run out of gurneys, we find chairs in hallways. When we run out of chairs, we treat patients in the waiting room

In November 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children's Hospital Association requested the White House declare a public health emergency in response to this season's overwhelming wave of pediatric respiratory illnesses. In the same month, the American College of Emergency Physicians issued a letter to President Biden alerting him to the immense strain of patients crowding our emergency departments. Yet the White House Winter Preparedness Plan did not address the staffing and spacing crises facing our frontline health services. The assumption that hospitals can fix the problem on their own is folly. In fact, some health systems have done the opposite, cutting resources to their emergency departments partly due to misaligned economic incentives. A number of COVID-19 after action assessments have explicitly advised against such decisions since they increase vulnerabilities to future pandemics and other public health disasters.

Such oversights cannot be reduced to individual institutional failures. Rather, these are symptoms of systemic deficiencies with only one redress: national and state-level policy interventions with appropriate funding and robust enforcement. Safe staffing metrics need to be established for standard of care in the emergency department. Safe spacing must also be determined, and this should be done in lockstep with our colleagues in industrial hygiene and occupational safety who specialize in the biosecurity of the built environment. Medicine does not always have the ability to act in its best interests if it does not have the appropriate expertise, which in this case, we do not.

These policies should have been enacted well before the arrival of COVID-19. Three years later, our inability to resolve these problems portends an even greater challenge when the next outbreak arrives. Without necessary and prudent investments in our essential frontline health services, there is only more pain in our future. The situation is dire. But it is not too late. We are all tethered together, and when one of us slips we can all fall down. The ascent may seem steep, but it is within our power to strengthen the ties that bind us and pick each other back up again.