In September, the World Health Organization (WHO) hosted the eleventh round of talks by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB), which the World Health Assembly created nearly three years ago to negotiate a WHO pandemic agreement. The draft text produced during INB11 was sobering for advocates of a robust treaty to address problems encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially inequitable access to vaccines and other health products.

The draft text reflects that WHO member states still have not reached consensus on many provisions of the Pandemic Agreement, including on the definitions of important terms and concepts. Most of the commitments on which negotiators have reached common ground are not transformative. On issues many countries have considered critical, such as pathogen access and benefit sharing, member states reached a stalemate again and proposed having the parties to the treaty negotiate solutions at a later date.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus captured the disappointment of many in global health by arguing that INB11 did not make enough progress. The latest negotiating round, however, could dictate what progress means going forward. The INB11's outcome portends the adoption of a watered-down pandemic agreement and future negotiations on contentious issues the results of which only a limited number of countries might accept.

The Road to INB11

The global COVID-19 disaster prompted proposals for creating a treaty to transform how governments deal with pandemics. In 2021, the World Health Assembly established the INB to negotiate a "WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response" and submit the outcome for the assembly's consideration in May 2024. Nine negotiating rounds did not produce consensus by that deadline, so the assembly extended the INB's mandate for one year. In July, INB10 focused on the modalities for the extended negotiations.

Even with a clarified agenda and more diplomatic space, INB11 struggled to advance the negotiations

Treaties often take considerable time to negotiate. Established after a once-in-a-century pandemic, the INB faced serious challenges. The negotiators had to sort through proposals from WHO member states about what a pandemic agreement should include. The INB also had to operate alongside negotiations on amending the International Health Regulations (IHR). As Suerie Moon argued, the "parallel talks created headaches both for developing countries, which typically have smaller diplomatic missions, and for nations with larger delegations, given the complexity of coordinating across government departments."

By INB11, the negotiations had whittled down the issues for a pandemic agreement and no longer faced competing pressure because the World Health Assembly adopted amendments to the IHR in June. Even with a clarified agenda and more diplomatic space, however, INB11 struggled to advance the negotiations, especially concerning issues on which WHO member states have disagreed since the INB began.

Difficulties With Solidarity and Equity

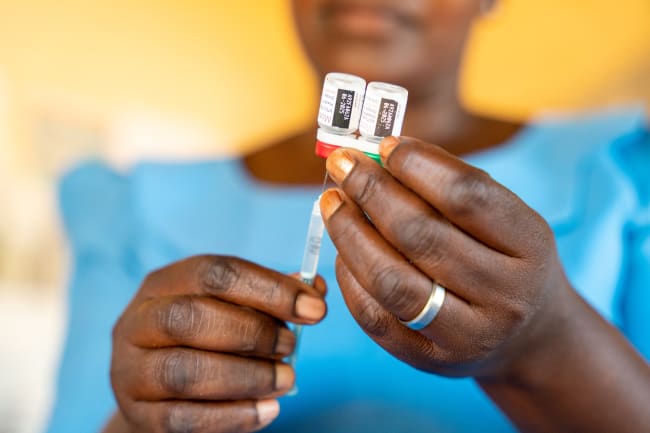

The experience of inequitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and other pandemic-related health products prompted many low- or middle-income countries (LMICs) and global health leaders to insist that the Pandemic Agreement should strengthen global solidarity through more equitable collective action against pandemics. The INB took up that call to action by, among other things, negotiating provisions on geographically diversified production and distribution of pandemic-related health products, the transfer of technology and know-how to support such production, and a pathogen access and benefit-sharing mechanism.

The draft text produced by INB11 indicates that WHO member states have reached initial agreement on the provision concerning geographically diversified production and distribution of pandemic-related health products. That provision, however, creates weak obligations to support, facilitate, and encourage certain goals that are subject to a party's determination about whether the specified actions are appropriate and compatible with its domestic law.

The draft text also indicates no agreement on definitions for pandemic-related products, transfer of technology, or know-how. The part on the transfer of technology and know-how is a patchwork of provisions that reflect initial agreement, initial convergence, or no consensus. The obligations in this part are undemanding (for example, promote and facilitate specific objectives), many of which are subject to applicable domestic and international law on intellectual property rights.

The draft text also suggests that WHO member states have reached no consensus about mechanisms to strengthen implementation of, and compliance with, the Pandemic Agreement's obligations. The text reflects initial agreement on approaches that have proved ineffective in global health agreements, such as periodic reports by parties and a standard dispute settlement mechanism. Unlike the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the draft text of the Pandemic Agreement permits reservations to provisions that a party does not accept.

Since the INB's first round, controversies have hovered over what many LMICs and global health advocates have viewed as the most important element of a pandemic treaty—a pathogen access and benefit-sharing system. INB11 did not resolve those controversies.

Instead, WHO member states reached initial convergence that a WHO Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing System (PABS System) should be established for pathogens of pandemic potential. They agreed, however, that the parties to the Pandemic Agreement should negotiate how the PABS System functions in a separate instrument (PABS Instrument). In short, WHO member states concluded that they could not produce a consensus pandemic agreement during the INB's extended mandate because of disagreements over the PABS System.

That decision breaks the Pandemic Agreement into two parts—what some commentators have called a "pandemic agreement lite" and the PABS Instrument. Based on the draft text, that instrument would only be binding on those parties to the Pandemic Agreement that specifically accept it. That approach could mean fewer WHO member states accept the PABS Instrument than join the Pandemic Agreement—an outcome seen elsewhere, including with the FCTC (183 parties) and its protocol on illicit tobacco trade (69 parties).

Problems with Pandemic Prevention, Surveillance, and One Health

Many advocates for a pandemic treaty emphasized the importance of improving pandemic prevention and surveillance through a One Health approach. The draft text from INB11 indicates that WHO member states reached initial convergence on obligations on disease prevention, surveillance, and One Health.

Those obligations, however, are weak or subject to a government's available resources, domestic laws, and applicable international law. The draft text reflects no consensus on proposed provisions that would strengthen the prevention, surveillance, and One Health obligations through the development of a separate instrument, which contrasts with the support that strategy received concerning the PABS Instrument.

One concern that LMICs have about obligations under the Pandemic Agreement, including those on One Health, is the need for funding to support implementation. The INB11's draft text does not mandate that high-income countries provide financing. WHO member states reached initial agreement on aspirational provisions that require parties to maintain or increase domestic spending, mobilize resources to support developing countries, promote innovative financing, and encourage inclusive, efficient governance of existing financing bodies—all subject to a party's determination of feasibility, available resources, and domestic law.

The INB11's draft contains a roadmap for concluding the Pandemic Agreement when the World Health Assembly meets in May 2025

The draft text reflects initial agreement among WHO member states to create a coordinating financial mechanism. The mechanism will not provide funding but instead work to increase the transparency, coordination, and accessibility of existing sources of financing, especially for developing-country parties. Improving the financing process is a worthy goal, but it does not address the underlying and long-standing inadequacy of financing for improving pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response.

It Ain't Over 'Til It's Over

Concerns about the INB11's outcome are important, but bargaining resumes at the twelfth round of INB negotiations in early November. What emerges from INB12 might undo agreements achieved earlier, strengthen obligations that have support, turn convergence into agreement, or overcome disagreements to produce consensus on important provisions.

Whether INB12 can produce a consensus pandemic agreement in time for a special session of the World Health Assembly to adopt in December seems unlikely given how much the INB11's draft text had not achieved initial agreement. The INB11's draft, however, contains a roadmap for concluding the Pandemic Agreement when the World Health Assembly meets in May 2025—agree to weak obligations, avoid strong implementation and compliance mechanisms, and defer disagreements over the PABS System to future negotiations on a separate instrument.

The Shadow of the U.S. Elections

Some commentary has identified the U.S. elections in November as a reason to conclude the Pandemic Agreement before a new presidential administration takes office in January 2025. The concern is that a second Donald Trump administration could damage the agreement's prospects. Sustained opposition by Republicans at the state and federal levels foreshadows the agreement's fate under a second Trump administration. It would be better, the thinking goes, to finish the agreement under President Joe Biden, who might sign it.

A Trump victory, however, would mean that any action by the Biden administration on the Pandemic Agreement in its last weeks would have no sustained effect. As he did with the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, Trump, as president, could withdraw the United States from the Pandemic Agreement and signal that, during his time in office, the U.S. government would not support it.

A Kamala Harris win would not ensure smooth sailing for the Pandemic Agreement in U.S. politics. Republicans have argued that the agreement should be subject to Senate deliberation and approval. A Harris administration would not get the constitutionally required two-thirds majority of Senators to approve the agreement because Republicans, who could regain control of the Senate after the elections, would oppose ratification.

A Harris administration could avoid Senate involvement by arguing that the president's constitutional authorities allow Harris to commit the United States to the Pandemic Agreement. President Barack Obama took that approach with the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Such a decision could create problems for the administration concerning the Senate's powers over budgets, legislation, and the appointment of ambassadors. Whether Harris would pick a fight with a Republican-controlled Senate over the Pandemic Agreement is not clear.

Avian Influenza and All That

Diplomacy and politics focused on the Pandemic Agreement have been churning as post-COVID outbreaks—including avian influenza, Marburg, and mpox—remind countries of the dangers that pathogens pose and the ongoing inadequacy of collective action within and among countries about such dangers.

The Pandemic Agreement draft text that emerged from INB11, however, raises questions about whether WHO member states are willing or able to transform global cooperation on pandemic threats as multilateralism falters, outbreaks continue, and climate change surges.