For nearly a decade the Chinese government has pursued a strategy of global infrastructure development, known as the Belt and Road Initiative, to build its influence. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, China resurrected semi-dormant plans for a Health Silk Road that would extend Beijing's vision of global health governance. Since then, China has consistently invoked the Health Silk Road as it subsidizes or donates medical supplies to COVID-19 stricken countries as a form of "mask diplomacy." More recently, China has begun a program of "vaccine diplomacy," strategically donating vaccines supplies to at least forty-nine countries—all but one of which are participants in the Belt and Road Initiative—and inking commercial agreements with twenty-eight others. By March 2021, one-third of nations classified by the World Bank as "low-income" were using at least one Chinese vaccine. As the Council on Foreign Relations' Yanzhong Huang has argued, through the production and distribution of its vaccines, Beijing can be expected to achieve an increase in its soft power in the form of "prestige, goodwill, perhaps a degree of indebtedness, even awe."

Following the delivery Chinese vaccines, at least 25 countries, including U.S. partners, have expressed support for China's core interests

China's vaccine diplomacy is already starting to pay political dividends. When president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, requested access to Chinese vaccines, he reiterated that the Philippines would not confront Beijing over its claims in the South China Sea. Following the delivery of Chinese vaccines, at least twenty-five countries, including U.S. partners like Ethiopia and Pakistan, have expressed support for China's "core interests," a common euphemism for the Chinese government's policies towards Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Xinjiang province. China has also sold or donated vaccines to countries to regions and countries where China has sought to expand its influence, such as Eastern Europe and Egypt. Policymakers in Paraguay, a longtime ally of Taiwan, are even toying with the possibility of reworking their East Asia policy to secure Chinese vaccines.

The Health Silk Road has also helped Chinese businesses cement ties in critical markets. Sinovac, one of China's vaccine manufacturers, has signed contracts with Mexico, Indonesia, Ecuador, and Chile. By proffering vaccines to Brazil, China may have helped open up the country's 5G marketplace for the Chinese firm Huawei after it had been previously locked out. China has also used the Health Silk Road to market its AI-powered diagnostic technology and 5G-based remote health care networks. Going forward, China will surely continue to use the relationships created by its Health Silk Road to deepen commercial ties and advance its strategic interests.

Despite the impressive appearance of China's efforts, its vaccine rollout has had some fundamental weaknesses. China has struggled to overcome public skepticism regarding the quality and efficacy of its vaccines. Polling from around the world shows that the public is most distrustful of Chinese vaccines. The public's hesitancy may be well-founded—earlier this month, the head of China's Center for Disease Control and Prevention conceded that the efficacy of Chinese vaccines is currently "not high." China may also strain to fulfill foreign commitments as it also carries out an ambitious domestic vaccination effort. As a result of capacity constraints, many Chinese donations have been of limited size, and sometimes amount to little more than a public relations event. These shortcomings offer the United States a window of opportunity to reassert its leadership in global health.

Before COVID-19, the United States was the undisputed leader on global health issues, the country that others around the world looked to for advice, cutting-edge research, access to medicines and medical devices, technical assistance and financial support, both from its government and from leading non-profits such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. But due to cutbacks in funding, a short-lived withdrawal from the World Health Organization, and a "me-first" approach to the pandemic—particularly in regards to the manufacture and distribution of vaccines—China's Health Silk Road initiative has begun to chip away at U.S. preeminence. As our new CFR-sponsored Independent Task Force report on China's Belt and Road Initiative argues, successfully countering Chinese efforts will require the United States to take a more active role in global relief efforts, put aside "vaccine nationalism," and make domestic investments to ensure it retains its position as the leading developer and provider of pharmaceuticals and medical devices.

Successfully countering Chinese efforts will require the United States to take a more active role in global relief efforts

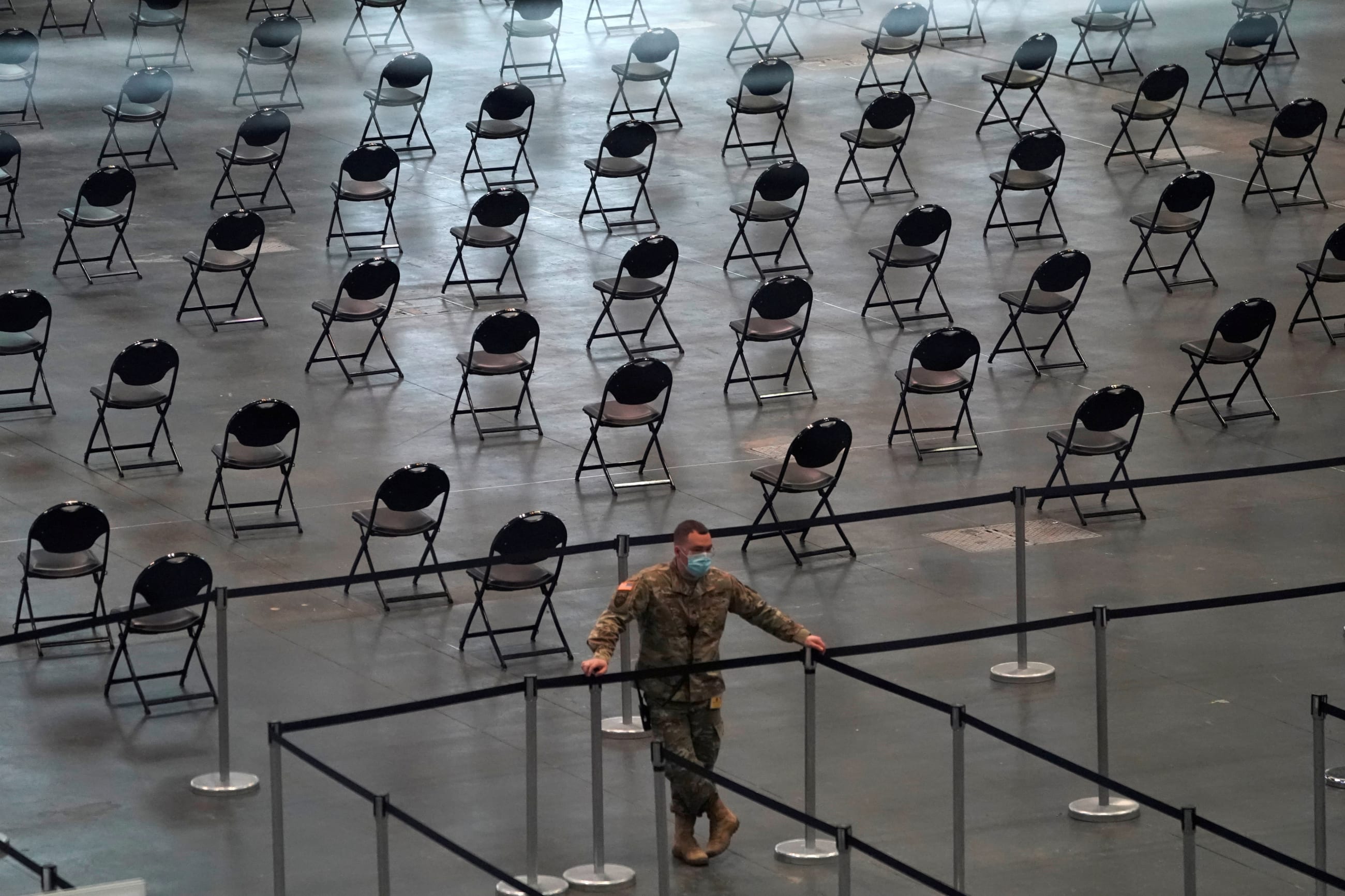

The Biden administration has made a good start with the creation of the Quad Vaccine Partnership, which pools the talents and resources of the United States, Japan, India and Australia to provide one billion vaccine doses to Southeast Asian nations. With the United States and Japan providing financing to India's highly developed vaccine manufacturers and Australia pitching in its expertise and distribution networks in the region, the plan hopes to provide a high-quality alternative to Chinese vaccines for people in the Indo-Pacific region. The Biden administration has also recommitted the United States to the World Health Organization (WHO) and pledged to contribute four billion dollars to COVAX, the group seeking to distribute vaccines among developing nations.

These actions are laudable, but they fall short of what is required. COVAX's efforts, for instance, have primarily been constrained by a lack of vaccine supply rather than a dearth of funding. Wealthy countries, including the United States, have secured most vaccine supplies, leaving little for the rest of the globe. As WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus put it, "If there are no vaccines to buy, money is irrelevant." The United States is estimated to have purchased four-hundred fifty-three million in excess doses, but, even with the global vaccine shortage, the Biden administration has failed to share many U.S.-made vaccines globally. Moreover, against the advice of advocacy groups and developing nations, the U.S. delegation to the World Trade Organization (WTO) joined representatives from other high-income nations in scuttling a proposal to loosen intellectual property rights around the COVID-19 vaccines that might have hastened increases in global production. Even United States' efforts to use its financing capability to expand global vaccine distribution may end up disrupted by the restrictions it has placed on the export of medical materials.

If the United States wants to offer a genuine alternative to the Chinese Health Silk Road, it will require both short-term and long-term investments. Over the coming weeks and months, the United States should ship more of its vaccines abroad, potentially by distributing a larger portion of the thirty million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccines currently stockpiled domestically and awaiting the completion of local clinical trials. While the Biden administration has sent shipments to Canada and Mexico, the United States should send more of these doses to a wider variety of countries. The United States should also ease export restrictions on medical supplies to avoid curbing global vaccine production. At the same time, the Biden administration should coordinate an immediate effort to scale-up global vaccine manufacturing and deployment, taking notes from its experience with Operation Warp Speed and building on the Quad Vaccine Partnership.

Over the long-term, to maintain a competitive edge vis-à-vis China in the global health arena and prepare for the next pandemic, the U.S. should substantially increase domestic investments in basic research and development, particularly in the technologies that increasingly make up advanced health-care diagnostics systems, health monitoring tools, medical devices, and bio-tech. It should also invest more in computer modeling and artificial intelligence to speed drug and vaccine development, along with enhanced support for new diagnostic tools and antiviral drugs and redouble teaching efforts in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) at all educational levels.

While no single government can address the threats to global health alone, the United States must act now to ensure that it is prepared to do its part

Moreover, the United States will need to provide sustained leadership in the international institutions and partnerships devoted to global health, particularly those that can help with surveillance and early warning systems for the next pandemic. No one is safe until everyone is safe; it remains in the United States' interest to mount a robust global response to the threats posed COVID-19, to provide an effective alternative to China's Health Silk Road and to prepare itself and the world for future pandemics and health emergencies. While no single government can address the threats to global health alone, the United States must act now to ensure that it is prepared to do its part while also responding to the risks raised by the expansion of China's Belt and Road into the global health arena.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Jennifer Hillman and David Sacks are co-directors of the CFR-sponsored Independent Task Force on a U.S. Response to China's Belt and Road Initiative, which is co-chaired by Jacob J. Lew and Gary Roughead.