International travelers spread COVID-19 rapidly around the world. For some, the takeaway was intuitive and clear: a more mobile, globalized world increases everyone's exposure to pandemics. Headlines like "Coronavirus Finds Fuel in a World of Migrants" reinforced this narrative.

If the intuition is correct, it has major implications for optimal travel and migration policies. Since any traveler at any time could be carrying the pathogen that will start the next pandemic, permanent restrictions on global mobility would save lives. Accepting this premise, leading researchers and journalists wonder whether COVID-19 represents "the end of an age" of global mobility.

In a recent working paper, we evaluated this claim directly, by assessing whether countries with more incoming international travel and migration at the onset of various pandemics—before anyone knew a serious disease was spreading—suffered more deaths by the time the disease had run its course.

Pre-pandemic global mobility did not exacerbate these pandemics

Analyzing four pandemics between 1889 and 2009, we find no evidence to support this intuitive model. The diseases crossed borders too quickly, and then spread overwhelmingly through domestic networks, for reductions in pre-pandemic international arrivals to make a meaningful difference in final mortality. Pre-pandemic global mobility did not exacerbate these pandemics, and preemptive policies would have significant economic costs and little benefit.

Our research should not be construed as testing the effectiveness of temporary travel restrictions during an ongoing pandemic. Such restrictions may be part of an effective mitigation strategy, like New Zealand employed effectively in the early months of COVID-19, although experts are skeptical about their effectiveness in most places. (As noted in an April article in Think Global Health, travel restrictions have not stopped the spread of COVID-19). Nevertheless, as of January 1, 2021, 96 countries banned travel from at least some countries.

Our study instead addresses whether rolling back international mobility after the COVID-19 pandemic would slow or stop the next disease with pandemic potential. Countries have a long, ugly history of inflaming fears that immigrants spread disease, with little or no basis in fact. Yet by our estimate, migration accounts for only 0.8 percent of international trips, undermining the logic of singling out immigrants as vectors of disease. Anticipating similar efforts after the COVID-19 pandemic, we evaluate the stated justification on its merits.

Reducing pre-pandemic mobility could affect final mortality in multiple ways. With fewer travelers to carry the disease, it might be slower in arriving, buying countries time to prepare. If this time is used to develop and adopt effective containment or treatment strategies, the delay could save lives. Additionally, countries with fewer travelers arriving before a pandemic begins could find it easier to temporarily shut off travel once the pandemic is indentified. But reducing travel would also reduce the flow of ideas, goods, and personnel that could directly bolster pandemic preparation and response when it is needed most.

Mortality from COVID-19 is ongoing, but we can turn to the influenza pandemics in 1889, 1918, 1957, and 2009 to evaluate these consequences in practice. These epidemics affected a broad number of countries, spread quickly, and killed varying shares of their populations, as documented in country-specific estimates.

First, we assess whether countries with more travelers experienced an earlier introduction of disease. For the 2009 Swine Flu outbreak, where pre-pandemic travel data are available, we can test this directly, and intuition proves to be a good guide: countries with more daily arrivals recorded their first cases earlier, on average.

Countries have a long, ugly history of inflaming fears that immigrants spread disease, with little or no basis in fact

But the magnitude proves insignificant. We estimate that if before the pandemic the average country had permanently cut its arrivals in half, including not only foreigners but also citizens returning from abroad, the disease would have arrived roughly one to two weeks later. Even these severe reductions buy countries relatively little time, because the exponential growth of a pandemic disease quickly overshadows the impact of the restrictions.

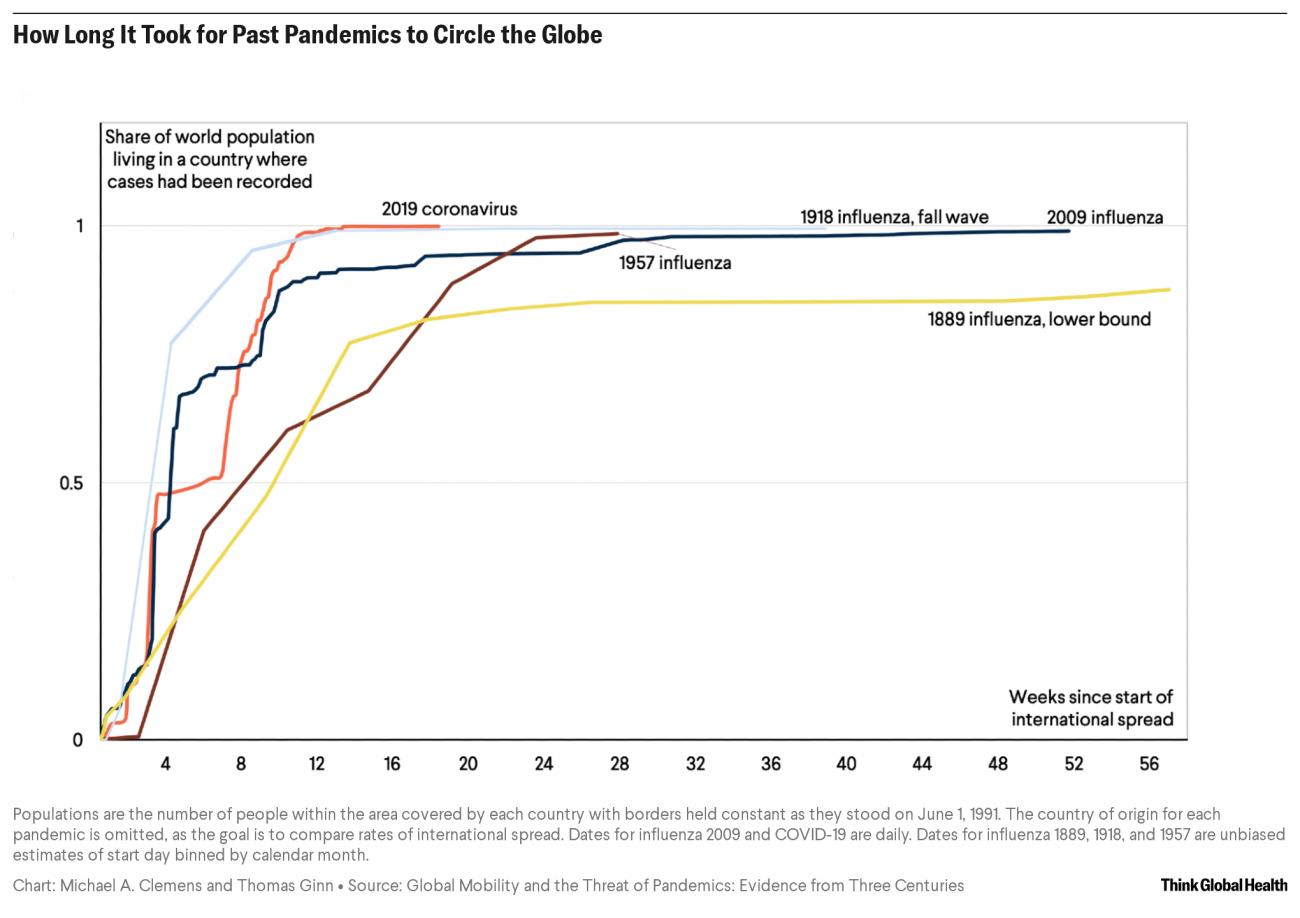

We also illustrate this relationship by observing how disease dynamics change across the four pandemics, as levels of mobility have significantly expanded. If mobility significantly affected disease transmission, recent pandemics should spread faster than earlier ones with similarly infectious pathogens. In Figure 1 below, we plot the time from the onset of international transmission to when the diseases reached different parts of the world. Where each curve hits the horizontal line through the middle of the graph, at 50 percent, shows the moment that each pandemic had reached countries containing the majority of the world's population. The timing of that moment across these pandemics, even as global mobility dramatically expanded over 131 years, only varied by about six weeks.

Although a reduced number of arrivals has minimal impact on onset date, it could still save lives if that additional preparation time enabled an improved domestic response. But in each of the four pandemics we find no correlation between onset date and final mortality. An early, robust response may be critical, but its effectiveness is determined by much more than a few additional days' notice.

Lastly, for the Swine Flu pandemic in 2009 we test the direct relationship between pre-pandemic international arrivals and mortality. Figure 2 shows the number of incoming trips per capita in 2008 on the horizontal axis and the respiratory mortality rate on the vertical axis. In this case, the mortality rate was actually lower in countries that were more exposed to international migrants and travelers before the pandemic. Even when we control for various measures of health system strength, economic activity, and population density, there is no sign of a positive association between exposure to visitors and the overall extent of sickness and death.

Swine Flu Mortality and Exposure to International Travel

During the 2009 Swine Flu Outbreak, Countries With Fewer Visitors Experienced Higher Mortality

We conclude that permanent travel restrictions would not have a meaningful impact on health outcomes — but it would have a severe economic and social cost. Millions of people are employed in international commerce and tourism, with large positive spillover effects on entire economies. Migration raises productivity and facilitates the exchange of ideas. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, migrants contributed roughly $6.7 trillion, or 9.4 percent, to global GDP in 2015—economic gains that can be invested into pandemic preparedness and health research. There is no better example of the positive effects of international mobility than the fact that children of immigrants to Germany developed one of the leading coronavirus vaccines.

When the world moves beyond COVID-19, we should seek to implement domestic and international regulations to save lives from future pandemics. Those include masking, social distancing, quarantining, contact tracing, remote working and shopping, public education, and pharmaceutical development. But restricting global mobility—and foregoing its many benefits—is not one of them.