For Erin Centa, the sense of guilt was immense. After her son Brandon was stillborn, she said, "I thought it was my fault. How could I, his mother, not protect him when he was in my womb? I failed at the most innate of motherly tasks."

Stillbirth, the loss of a fetus before or during delivery, is a devastating and often avoidable pregnancy outcome. Stillbirths are distinguished from miscarriages by how far along the pregnancy is, miscarriages occurring before 20 weeks' gestation. The World Health Organization (WHO) has previously recommended including stillbirths at 28 weeks' or greater in international stillbirth statistics. The shortcoming of this approach is that it leaves all fetal deaths between 20 and 28 weeks' gestation uncounted.

Our new study, published in The Lancet on November 4 as part of IHME's Global Burden of Disease study, estimates stillbirths down to 20 weeks' gestation—an earlier cutoff point than what previous global assessments have used. It found that approximately 3 million stillbirths occurred globally in 2021 after at least 20 weeks' gestation, averaging about 8,328 per day. This rate means, worldwide, one stillbirth happens every 10 seconds. Further, nearly one-third of these occurred between 20 and 28 weeks' gestation.

Comprehensive efforts to record and count all stillbirths are essential for informing public health interventions aimed at preventing them. We believe that using a lower gestational age cutoff for counting stillbirths is justified by improvements in technology and advancements in neonatal care that support extremely premature babies and increase their chances of survival, even when born as early as 21 weeks and one day.

One of these innovations is cardiotocography, a technique that uses an elastic belt to continuously measure a baby's heartbeat and contractions. Computerized monitoring of a baby's status in the womb has been shown to reduce infant deaths around the time of birth by 80% relative to when this approach is done manually with pen and paper.

Global Trends in Stillbirths

The global community's focus on and efforts toward reducing stillbirths have led to annual decreases since 1990, but the total number of stillbirths affecting pregnant people and families remains high. Reductions in stillbirths have not kept pace with global declines in neonatal and under-5 mortality. Even though the estimated number of stillbirths at 20 weeks' gestation or longer decreased by about 40% over the past three decades, this reduction was notably less than the approximate 45% decline in neonatal (<28 days old) deaths over the same period. Those trends indicate too little prioritization of stillbirth prevention, including resources for and attention toward maternal health care before and during pregnancy.

According to our findings for 2021, South Sudan recorded the highest stillbirth rate (68.3 stillbirths per 1,000 births). There, only about half of pregnant women (57.6%) received at least one antenatal care visit with a skilled provider, and less than a quarter (21.9%) received at least four. The largest deterrents for accessing antenatal care are reportedly long distances for travel and a lack of transportation to health facilities, as well as the inability to pay health-care fees. Conversely, in Slovenia, which had a low rate of 5.1 stillbirths per 1,000 births, almost all women received at least four antenatal care visits. Since 1998, preventative health-care policy in Slovenia has required at least 10 antenatal care visits and three ultrasounds during pregnancy.

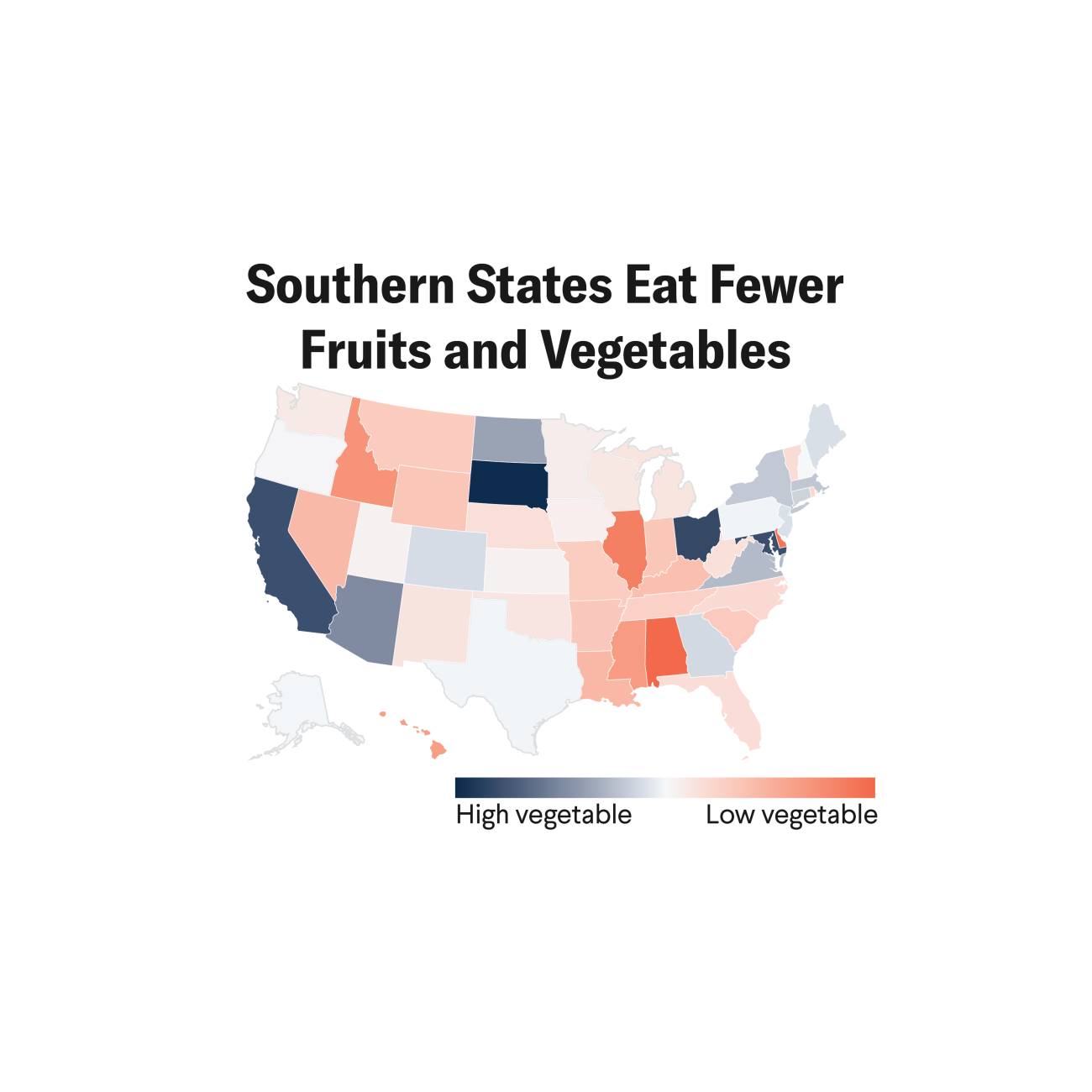

Trends in stillbirths vary across geographic regions, the stillbirth burden being most concentrated in countries with low sociodevelopmental status (defined as having low levels of education and income and high fertility). More than 75% of all stillbirths at 20 weeks' or longer gestation occurred in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa in 2021, increasing from 60% in 1990. Social inequalities in stillbirths are associated with access to and use of medical services, including midwifery care, emergency obstetric care, and family planning services.

The health status of the mother is a key determinant of pregnancy outcomes. In low- or middle-income countries, treatment of infections during pregnancy, especially malaria and syphilis, has been shown to reduce the likelihood of stillbirth. Having the opportunity to schedule and attend check-ups for the duration of the pregnancy is extremely important. In 2021, in 11 countries—including Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea, Somalia, and Yemen—fewer than 80% of mothers received one antenatal care visit during their pregnancy. Further, in 66 countries, fewer than 80% of mothers had four antenatal care visits.

Lack of timely care from a health-care provider and insufficient knowledge and training on the part of the health-care provider are also major risk factors for stillbirths. In India, for example, approximately 10.6% of births in 2021 were not assisted by a skilled birth attendant such as a nurse, doctor, or midwife. Rural populations in low- or middle-income countries could see stillbirth reductions of about 30% when a trained (versus untrained) traditional birth attendant is present for the birth.

In sub-Saharan Africa, fewer births take place in a health facility. Among these countries, five had fewer than 50% of births occur in a health facility in 2021: Chad (29.9%), Ethiopia (49.2%), Niger (38.6%), Somalia (35.7%), and South Sudan (12.9%). Even in health facilities, skilled birth attendants are not always available, and the quality of care can be inadequate. An estimated 25% of countries had more than 10% of births taking place without a skilled birth attendant in 2021.

Improving the quality and availability of prenatal care services and fetal monitoring, particularly in low-resource settings, can go a long way. Idowu, a midwife from Nigeria, described her experience in a country with one of the highest stillbirth rates.

"Seeing a woman beg you to save her child is heart wrenching," she said. "The reduction in the rate of stillbirth is possible if accessible and affordable health-care services become available to all pregnant women."

Every stillbirth is a profound loss and has lasting impacts on women and families. We encourage the global health community to continue focusing their attention on developing and implementing solutions to end preventable stillbirths.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors would like to thank Erin May for fact-checking the post, and Anna Gage and Katherine Leach-Kemon for providing feedback.