Development assistance for health is expected to decline in sub-Saharan Africa, and domestic spending on the issue is not rising quickly enough to close the gap despite forecasted economic growth. The trend is driven by a range of internal and external pressures, including shifting donor priorities and low political will.

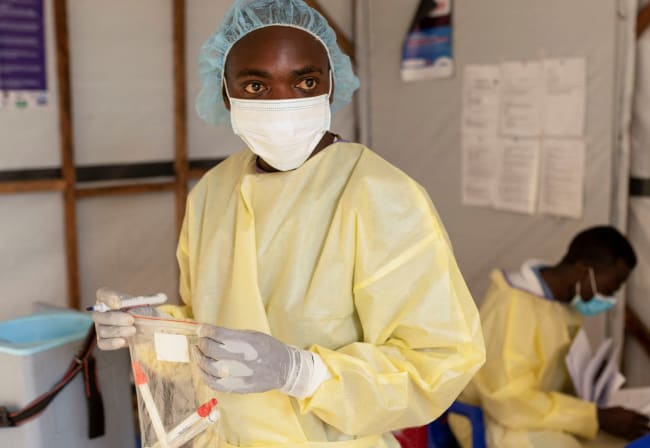

These findings feature in a new study from researchers at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), who analyzed health spending trends in sub-Saharan Africa to project how the future of health financing could look in the region. A drop in health system funding could devastate sub-Saharan Africa, particularly for countries such as Democratic Republic of Congo, now facing a growing outbreak of mpox amid a lack of medicines and armed conflict.

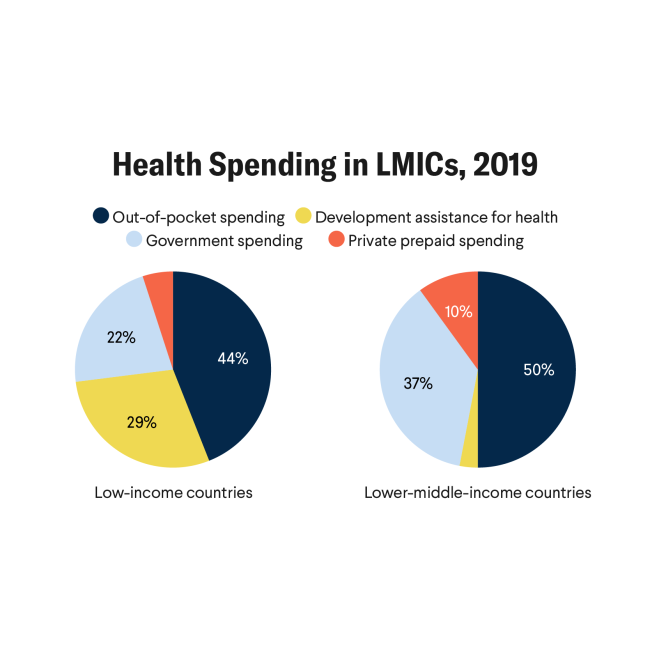

The study found that although gross domestic product (GDP) in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to increase through 2050, the share of GDP spent on health is expected to decrease in three (Central, Eastern, and Western) subregions. In 2021, half of sub-Saharan Africa's countries relied on external financing, such as grants and loans, for more than one-third of their health expenditures.

IHME's projections revealed that growth in development assistance for health will plateau or decrease in 13 countries through 2050. Think Global Health spoke with the study's lead author, Dr. Angela Apeagyei, about what is shaping financing trends and how policymakers can avert reversals of global health gains made in the region.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: Could you please summarize your key findings? What would you like people to take away from your study?

Angela Apeagyei: Two important takeaways: First, development assistance that's historically been high is leveling off and potentially declining. Second, economies are gradually bouncing back from the COVID-19 pandemic and moving toward a path of growth.

At least as it pertains to sub-Saharan African countries, the proportion of the general government spending that goes to health—even though it may be increasing—is not rising at the pace that will make up for the decrease in development assistance.

A potential future with gaps in health and financing is being created: Of two of the main sources of financing, one appears to be declining and another is not rising high enough, which is associated with countries' prioritization of health in their budget, or lack of it.

The more that decision-makers see health as an investment in the economy, the stronger the case for prioritizing it

Think Global Health: Could you expand? Why would countries not prioritize health in their budget, and what is driving that trend?

Apeagyei: Every country has the freedom to determine the priorities of its national revenue. Even on a limited budget, you choose to prioritize certain things and provide for certain things. So, one driver, I would argue, is political will.

There are always competing demands on the budget, especially for sub-Saharan African countries still in the process of developing their economies, meaning demand for roads, water, and many other things. All of these are important.

But the more that decision-makers see health as an investment in the economy, the stronger the case for prioritizing it. Historically, the health sector has been seen as a recipient of government funds, but studies show that better health helps boost the economy. The more that leaders appreciate the role that investment in the health sector can have on a country's broader growth, economic growth in particular, maybe the more priority they will give to the health sector in the government budget.

Other drivers limiting a government's ability to prioritize health can be internal and external. Internally, governance structures and leakages or inefficiencies in the public system can be barriers to investing in health. Externally, government obligations impinge on the fiscal space the government has—the resources available and the flexibility the government has in allocating them.

So, governments have both the internal challenges with procurement, governance, leakages, efficiencies in resource processing systems, and then the external challenge of taking on loans that have to be repaid. All impinges on the total envelope of funds a government can allocate. If the bucket is smaller, they give up some priorities to cover their obligations or access additional funding from international organizations. All of that strains the resources the health sector has available.

Think Global Health: Why is developmental assistance declining? What might that mean for countries in sub-Saharan Africa?

Apeagyei: Development assistance has dropped off from a period of very high growth, such as the 2000s' Millennium Development Goals era and its rates of 11% annual growth, to rates of less than 5%. Financing then hit a plateau, but COVID-19 conditions gave rise to a huge jump in development assistance in 2020 and 2021. In our team's most recent data, however, the support is now on the decline and approaching pre-pandemic levels.

A few things are occurring. First, the COVID-19 pandemic was a true pandemic: It happened all over the world and high-income countries felt the financial pinch. When that happened, donor governments found that they needed to make a better case to their population about why they were spending money on global health as their citizens faced economic challenges. One example is the United Kingdom, which changed the percentage of gross national income that it gives overseas so that it could focus on making things right internally.

Anecdotally—our team does not have data yet to back this up—there is a sense that more donor interest is on issues of climate change and the environment than issues of health.

There is also interest in supporting global public goods—ones that will benefit everybody and global health security. That's important but slightly different from what's needed in countries to build robust health systems. Related to an earlier point, it seems harsh but donor countries seem less bothered about what's happening in the world and want to find solutions to their internal problems.

Think Global Health: Your study makes projections through 2050. What can policymakers do differently to avoid the negative effects of health financing gaps?

Apeagyei: One of the key reasons for working on this paper was trying to look a little further out and predict what's coming. What policymakers can do, to my earlier point, is to use the argument that investing in health is investment in the economy, and that a healthy population will be more productive.

The focus should be on providing not only more hospitals, but also all the different things that the health sector needs to thrive: adequate health workers who have the tools, medications, proper equipment, and protections to treat the populace.

Countries should focus on public health and prevention, a populace that's educated enough to know when to seek care

Countries should focus on public health and prevention, a populace that's educated enough to know when to seek care. The economic angle is not new. But in times of constrained budgets, high debts, contentious election cycles, it's a helpful argument to prioritize the health sector.

For donor governments, the biggest argument for continued support of development assistance is the progress that has already been made on antiretroviral therapy, child mortality rates, HIV, and immunization levels. Given historical support, it would be a shame to pull back and lose some of that progress that countries have made. I agree, to a certain degree, with pulling back at a certain point, because donor countries cannot continue to support other people forever. But such planning should be better and made gradually within the right system so that governments are in a position to take up that additional responsibility.

Think Global Health: Any major factors you foresee affecting this progress?

Apeagyei: A number of African countries are exploring the potential for public health insurance programs to support universal health coverage.

Outside access to services, this involves making sure that when people show up to the facility, it's not a death trap. Patients need to receive care that will improve their health. They need to see appropriate health workers, drugs in the facility, and cleaning agents so they can feel confident that infections are not spread.

The push to improve coverage through the public provision of insurance is one of the positive things that I hope in the next few years countries make progress on, both on the demand side and the supply side: encouraging people to go, but making sure that the services are good quality.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This interview has been edited lightly for clarity.