The United States recorded an additional 100,000 COVID-19 deaths in the last three months, bringing the country's grim toll to 200,000 American lives lost to coronavirus. Despite recommendations, our new analysis shows that the country has made little progress in improving data reporting systems that would provide health officials with the most basic information and meaningful analytics they need to understand the dynamics of the pandemic's hold in the United States and make critical public health decisions, including ways to protect certain populations and communities of people who are at increased risk of contracting coronavirus and dying from it.

The grim toll of U.S. COVID-19 deaths this week reached 200,000 American lives lost

We know that Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian Americans become infected with and die from COVID-19 at higher rates than white Americans, and we are seeing that the contributing factors that drive these disparities are different for each population group. Recent research looking at Massachusetts cities and towns showed that crowded housing, employment in the food-service industry, and being a recent immigrant are COVID-19 are all risk factors for Latinx communities. Black communities are at risk because of abundant in multi-unit building housing, higher rates of public transportation usage, and more people residing in polluted environments. Those risk factors are surely playing out in actual case numbers and are relevant to understanding why Black and Latinx people across the United States are being infected and dying at higher rates—yet, our new analyses shows that social and community-level information like this is not being reported. In fact, there's no place to even record this information on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case report form, which the CDC developed to standardize the reporting of information on COVID-19 cases across the country with the objective of informing public health response to prevent further spread of coronavirus.

In May, we began tracking how COVID-19 data is reported and analyzed across the United States by examining seventy-two COVID-19 data sources from the CDC and health departments across all fifty states and the District of Columbia, ten major U.S. cities, and ten other hot spots, including: Madison, Texas; Chicot, Arkansas; Chattahoochee, Georgia; Jefferson, Florida; Cibola, New Mexico; and Tallahatchie, Mississippi.

Woefully inadequate and inconsistent data collection and reporting efforts

We found that the country's data collection and reporting efforts are woefully inadequate and inconsistent. For three months, we continued tracking what data was captured (completeness) and what factors were analyzed when looking at COVID-19 testing and the four key outcomes: cases, hospitalizations, recoveries, and deaths. We assessed how this data was disaggregated by key indicators, including age, race/ethnicity, sex/gender, geography, and underlying health conditions. Our methodology, datasets, and in-depth analyses are available through Dataverse.

What the Analyses Found—Completeness and Disaggregation of Data

In August, fifty states and Washington, DC, scored an average of 16.3 out of the 30 points for overall completeness of data—a two-point increase since May. Thirty-four states and Washington DC reported data on testing, cases, hospitalizations, recoveries, and deaths—a small increase from our initial analysis on May 31. The number of data sources reporting on testing increased from forty-nine to fifty and on recoveries from thirty-two to thirty-eight. We determined completeness of data by whether each data source reported on five outcomes, including testing, and if those were disaggregated by five demographic indicators. Each source received a point for an outcome and an additional point for each demographic indicator it included for each outcome, equating to a total of thirty points per data source.

Less than 40 percent of all data sources incorporate race/ethnicity into their intersectional analysis for any outcomes

While we saw improvements in the disaggregation of COVID-19 testing and outcomes by key demographic indicators, this remains fundamentally insufficient. Across the fifty states and Washington DC, thirteen states improved in their disaggregation of demographic indicators for testing, eleven for cases, sixteen for hospitalizations, ten for recoveries, and seventeen for deaths compared to May. A majority of states reported cases and deaths by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geography. However, this information is far less available for testing, hospitalizations, and recoveries.

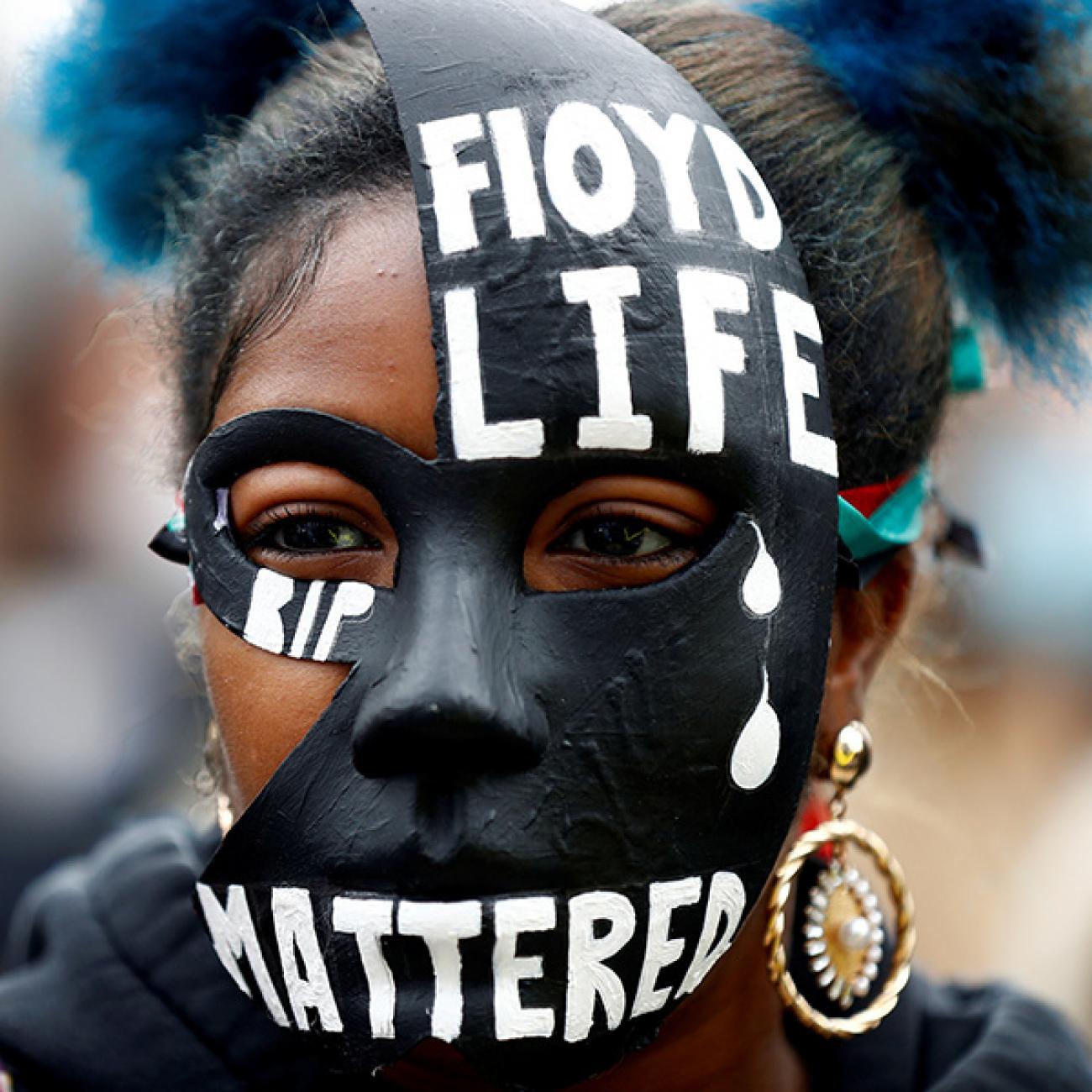

We also examined whether states and cities conducted intersectional analysis by investigating how multiple social and demographic indicators interact to affect COVID-19 outcomes. Of the seventy-two data sources, only thirty-eight (compared to twenty-two in May), conducted intersectional analysis. Even given the heightened awareness of racial inequity brought on by COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement, less than 40 percent of all the data sources incorporate race/ethnicity into their intersectional analysis for any outcomes.

Gender, Race, and Poverty Data. Gender data is limited to male or female. While six states and cities (Pennsylvania, California, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Nevada, and New York City) claimed to have started collecting data on gender identity and sexual orientation, no sources have actually reported this data. In addition, data on race and ethnicity are inconsistently reported, and New York City and Los Angeles are still the only two data sources that report on poverty-level data.

Community level information, such as the location of infection and how certain population groups are exposed to the virus, is crucial for testing, contact tracing, and isolation strategies. Yet data on factors such as "place of stay during illness onset" and exposure information is generally unavailable—and where it does exist, it varies drastically between states. For example, most data sources only include long-term care facilities as information on "place of stay." Without data on other places of stay, it is impossible to identify residency trends, including how the coronavirus is affecting people in prisons and other correctional facilities, homeless camps, group homes, or low-income housing—all places that oftentimes have disproportionately high percentages of marginalized populations.

Disproportionately high percentages of marginalized populations

Further, health-care workers are at high risk of contracting coronavirus and the majority of U.S. health workers who have died of COVID-19 so far are people of color and nurses. We found that states and cities reported information on health-care workers in varying ways. Only seventeen data sources reported on health-care workers at all, and they varied in the outcomes (most reported on cases but others reported on deaths and recoveries) and the types of health-care workers (e.g., some sources but not others include long-term care facility staff).

Without adequate data on social, demographic, and community-level factors associated with COVID-19, city and state governments and health officials are severely hamstrung in formulating effective policies that could control the spread of coronavirus while protecting at-risk communities.

Officials are severely hamstrung in formulating effective policies

While our analysis showed that nineteen states and cities have already activated response teams on health equity to address the needs of minorities and marginalized populations during the pandemic, five did not even mention the importance of data. As states continue to reopen with schools and universities resuming daily activities, the country should prioritize data reporting of COVID-19 testing and outcomes and key demographic and exposure indicators based on the CDC case report form. Failure to do this and to broaden reporting and analysis of social and community level factors that may drive disparities will only widen the gap in health inequities.

A standardized COVID-19 data collection system can no longer wait if we want to suppress COVID-19 and understand how to tackle health inequity during the pandemic and beyond.

American lives depend on it.