For more than thirty years I have been working as a global health consultant. In 2018, together with a few colleagues, I attempted to organize a session at an international health conference that would critically examine the funding of health programs in "developing" countries by partners in "developed countries." This is often called "development aid," and there are lessons people working in this field can learn from movements like Black Lives Matter. Exploring those lessons and examining our past and present approaches could help make changes that will lead better local and global health systems.

The importance of decentralizing power, listening to, and taking seriously the expertise and needs of those most affected by a problem

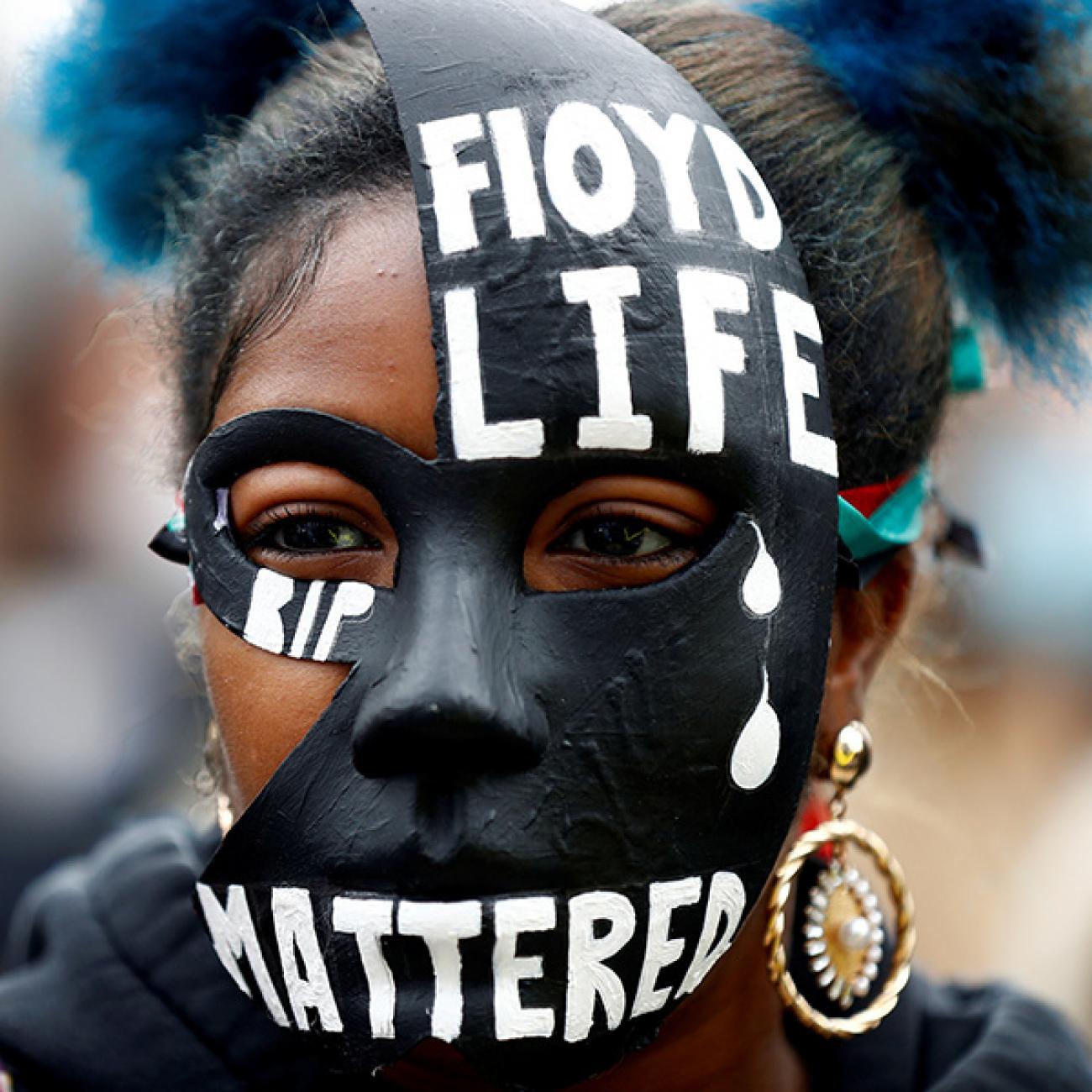

The Black Lives Matter movement has been an important awakening to the pervasive problem of police and other forms of violence against the Black community. But the movement's success also shows us the importance of decentralizing power, listening to, and taking seriously the expertise and needs of those most affected by a problem—rather than imposing top-down solutions by those considered "experts." Global Health has much to learn from this. My colleagues and I have been fed up with the unequal power structures in place, whereby many organizations responsible for funding global health projects do so in short two- to three-year contracts. These projects, for instance, focus on new ways to improve health facility quality, different mechanisms for financing essential health services, or capacity building for monitoring and evaluating health services.

All these are essential health system activities, but the short-term, offshore nature of their funding blunts their effectiveness. A successful contract winner on a typical global health project usually requires at least a year out of the three-year contract just to launch. The contract winner often needs to establish a relationship with local policymakers, health professionals or other stakeholders, inform them on how the project will work, and establish an office in the country or region.

Yet another new model of quality improvement—or financing, training, or whatever the partner from the developed world decided was necessary

The whole process puts stress on existing health systems, especially the often already overstretched people in the recipient country's ministry of health, regional health authorities, and health facility staff. Often the total number of running development health projects are more than the number of staff in the health agencies responsible for overseeing local cooperation with the projects. Ministries of health and others affected by the projects have to come to terms with yet another new model of quality improvement—or financing, training, or whatever the partner from the developed world decided was necessary. By the time they do, a new contract has been agreed with a new consultancy company with new ideas, and the three-year cycle starts again.

The conference session we proposed two years ago sought to address this by focusing on how this type of three-year funding weakens health systems. But despite positive feedback from several colleagues, our proposed session was not accepted that round, nor was it accepted in the two years since. In the end we were allowed to present our findings in a poster session.

Positive, quantitative progress fails to tell the whole story

This reluctance to self-reflect has been typical of global development aid. Reflection, when it happens, typically focuses only on the successes and ignores the difficulties in getting there. Don't get me wrong—there are plenty of outstanding positive outcomes tied to development aid: maternal mortality has decreased in most countries, there has been some improvement in vaccination coverage, and malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS have decreased in incidence. But positive, quantitative progress fails to tell the whole story. Are short-term contracts really the most efficient use of money, time, and human resources?

My issue is not on how much global partners should give—we all know that global partners are not meeting their commitments. In 1970, as proposed by the United Nations Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OEDC) through their Development Assistance Committee (DAC), the world's highest-income countries agreed to give 0.7 percent of their gross national income as official international development aid annually. But only six countries (Luxembourg, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) have met this target.

The result are short-term, disjointed and unsustainable initiatives

My issue is rather on how these billions of dollars are spent—and especially that these decisions are made by a global elite in isolation from each other and often with little input from those who will be most affected by the projects (the supposed beneficiaries). The results are short-term, disjointed, and unsustainable initiatives. For instance, during my work in a South Asian country, I was involved in a regional project on improving health-care standards. I approached another health-care quality improvement project, funded by a different international donor, to align our efforts as much as possible. I met with the leader of this project and his team, and before our offer was rejected, he queried whether our project could even have any success as we were working closely with the local government—a government he considered to be "riddled with corruption." He felt his project's result would be much stronger without their influence. Today that local government is still there, but his project result is hardly visible.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for strong public health systems and existing health system gaps, including in the wealthier countries. In addition the novel coronavirus has also exposed social inequalities, forcing us to examine the social and health injustices in our countries.

Voices not heard by powerful elite who make critical decisions on global health

Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, has written about some revolutionary movements in the global health field, including an article in September 2018 about our false notions about the history of global health. Horton points out that it was Frantz Fanon, a Black doctor from Martinique, who strongly influenced the first manifestos for global health. Fanon's message, and other historically ignored voices who have challenged our current systems for promoting global health, have not been heard by the powerful elite who make critical decisions on global health. This elite continues to tinker with health systems but seem incapable of making significant changes.

Maybe they will listen if more of us challenge the status quo. This month the Guardian published an article titled, "The aid sector must do more to tackle its white supremacy problem" with the subtitle, "Racism is embedded in structures and power dynamics, so we should logically conclude that we are not immune"—meaning we, the development aid sector.

It was an excellent article, but the fact that the name of the author is "Anonymous" is telling. Challenging the status quo could be professionally harmful, especially pointing out the lack of self-reflection in the aid sector and the engrained power dynamics. They support my points above that one of the major problems is failure to make progress towards localization—that is, increasing the role of national responders and placing greater value on local expertise and knowledge, including the use of local languages.

The concept of empowering local actions is engrained in several international agreements, especially the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness.

Most successful proposals still seem to be written by international consultants who may even manage the resulting projects

Its five fundamental principles of ownership, alignment, harmonization, measuring results and mutual accountability for aid results hold donors and recipients accountable for their commitments on development aid. The declaration bases development activities within local strategies, local systems and simple procedures, with sharing of information and aid results between donors to avoid duplication. In global health some meager attempts have been made to empower local actions, such as to contract with local consultancy companies, to engage local consultants and other non-government organizations, and to enable writing of development proposals by local committees. However, with short timeframes and a dearth of proposal-writing experience among local actors, most successful proposals still seem to be written by international consultants who may even manage the resulting projects.

Recently I had an experience in a sub-Saharan African country that illustrates many of the issues inherent in global development aid. Working in a project to train local government managers we turned to the national guidelines to ensure that we build on local practice and not reinvent the wheel.

Many policies and guidelines distributed through the health ministry in this country are in English, with no translation to the local languages

But we found the national guidelines, weighing in at more than one hundred pages, uses sophisticated, technical language—besides the fact that they are written in English and not available in the local language. The result was that most of the managers we were training had little knowledge of the national guidelines, compounded by the lack of monitoring of the guideline's implementation. One might assume that since English is the second language of this country, all regional and district managers would be fluent enough to read the guidelines, but that is not the case. Many policies and guidelines distributed through the health ministry in this country are in English, with no translation to the local languages. Yes, these documents are understood by those in the ministry but not necessarily by health workers in the local districts—and definitely not in the facilities where health professionals struggle to provide care and have little time to polish their English-language skills.

The anonymous author also addresses this issue in her/his article, writing, "We're told the local capacity doesn't exist, or that we are victims of an overly professionalized sector, requiring perfectly written English-language reports to headquarters and donors." The international organizations and donors act as an elite, requiring the locals to fit into their world of reports written in polished English. How many of these perfectly written reports end up on the shelf and are not read or understood, especially by the local actors responsible for enacting the recommendations/decisions included in these reports?

It is time we learn these lessons

Global health as a concept has been crucial in bringing health care and vaccines to many in the developing world, but unless it works towards actually being guided by local experts and is sensitive to local context, it will continue to perpetuate global systems of injustice. Black Lives Matter and other movements show how power can shift to those historically not given power, and it is time we in global health listen and learn these lessons.