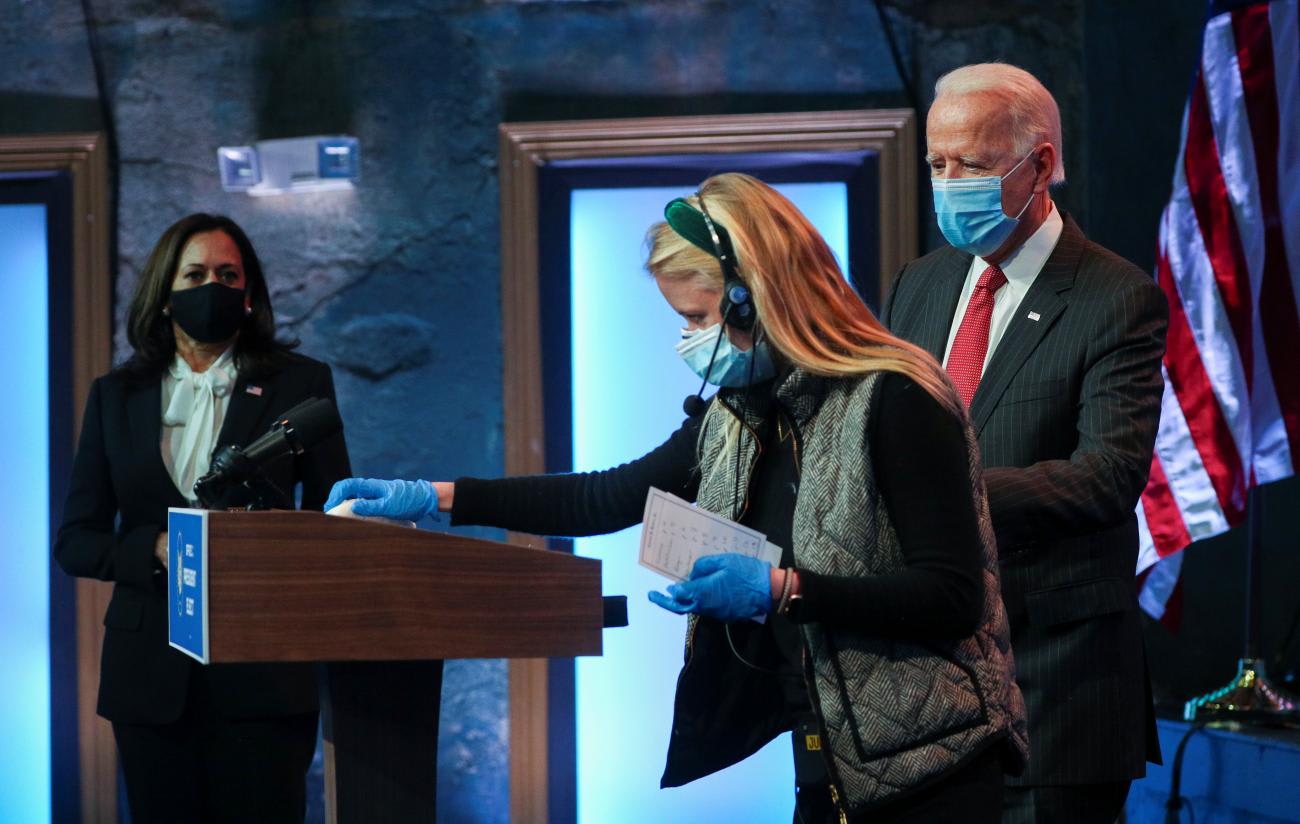

Just days after Election Day in the U.S. President-Elect Joseph R. Biden and Vice-President-Elect Kamala Harris announced the formation of a new, COVID-19 task force. Many have proposed "to-do" lists for the new task force–ensuring that safe and effective vaccines are produced, distributed and efficiently administered; that effective treatments for COVID-19 patients are available; and that affordable mass testing is widely accessible. But even as the task force tackles a long to-do list, it has the challenging task of undoing much of what has been done by the current administration. By blatantly ignoring public health experts and ricocheting "from one overhyped cure-all to another," we are now beset with competing messages about risks, social norms and even beliefs about the existence of this new deadly pathogen. Unwinding these messages and promoting the unlearning of these behaviors is a crucial task for the new administration.

By blatantly ignoring public health experts, we are now beset with competing messages about risks, social norms and the existence of the virus

When COVID-19 arrived in the United States in early 2020, public health experts advised the general public to increase their frequency of hand-washing and adopt new behaviors like physical distancing and, eventually, mask-wearing—and to drop others like shaking hands and attending large indoor social gatherings. Experts understood that slowing the transmission of COVID-19, in the absence of any natural immunity to or vaccine for a novel pathogen, would ultimately require people to change how they think and act. This was no small task in and of itself, but was further complicated when the White House modeled behavior that accelerated the spread of the virus rather than reducing it.

Behavioral scientists have helped foster changes necessary for challenges as diverse as reducing smoking, fighting Ebola, and fostering healthier diets and breastfeeding. That experience yields five insights that can help create large-scale behavior change—including unlearning and undoing what got us here—to prevent further transmission of COVID-19 and accelerate vaccine adoption.

1. Information is necessary, but insufficient. Arming people with information about the risks of COVID-19 and the value of masks and social distancing is crucial, but will likely not be enough. Early public health campaigns that discouraged smoking or promoting consumption of fruits and vegetables often assumed that people weren't making healthy choices because they did not know the risks and benefits of their behaviors. But experience has taught us that informing people doesn't, by itself, change behavior. This is especially true when people are trying to change deeply entrenched habits (e.g., shaking hands, touching their faces, social get-togethers). In these cases, people need constant visual reminders or they will simply default to their old habits, like getting too close to someone, even though they know they should respect a six-foot distance.

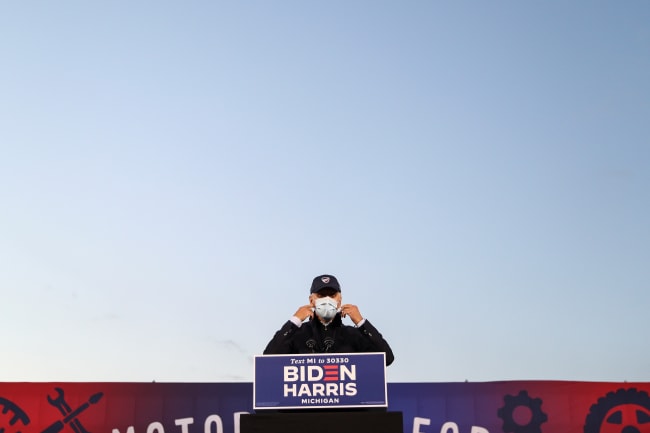

2. Social norms matter. They matter a lot. Humans are social animals, heavily influenced by the perception of what others in their communities are doing or are not doing and what actions they find worthy of approval. Understanding existing social norms and modifying them to create new social norms is crucial. We need to understand what is being transmitted as the norm with a variety of social groups and work with and through influential role models and marketing campaigns to influence and ultimately change social norms. We need to identify the critical norm breakers and setters in given social groups. It could be argued that President Trump was a powerful norm breaker (or a poor norm setter) who actively discouraged people from protecting themselves and each other, whether they were attending meetings in the White House or congregating at an election rally. In contrast, the next administration has already become a powerful norm setter by wearing masks, standing six feet apart, and not gathering in large groups. And when vaccines are available, prominent members of the White House can potentially increase the uptake if they are vaccinated and demonstrate that these are safe vaccines for all Americans.

The next administration is norm-setting by wearing masks, standing six feet apart, and not gathering in large groups

3. Seemingly irrational "nudges" can be more powerful than coercion. Research in psychology and behavioral economics has shown that people can be gently guided, or "nudged," toward taking a desired action by seeing their own choices differently. For example, changing defaults on organ donation programs from "opt-in" to "opt-out" dramatically increases enrollment. In the case of hand-washing in schools, painting colorful steps on the ground leading from the toilet to the hand-washing station significantly increased washing behavior among children. These examples show how slight nudges can influence behavior by modifying the context in which people make a decision. In the case of COVID-19, we need to nudge people toward enrolling in contact tracing, more frequent testing, and taking a vaccine when it is available. This can be done by creating the right choice architecture, so that people feel that they're making the best choice for themselves.

4. Make change easy. When we ask people to change an existing habit, we have to make healthier behavior as easyas possible – ideally, even easier than not doing it. For example, smoking bans have worked around the world to make the existing behavior (smoking) difficult and the desired alternatives (not smoking, or vaping) much easier by comparison, thereby promoting adoption of the new behavior (smoking cessation). Similarly, pill packs that automatically sort a person's unique daily medications into a combined pre-packaged dose significantly increase patients' adherence to their medication regimen. New task force member Dr. Celine Gounder emphasized this point and acknowledged that making these new behaviors—such as mask wearing, social distancing and routine testing for COVID-19—much easier is essential. For example, making masks and sanitizer easily available and accessible in work places, stores and schools helps promote behavior change.

5. Rewards are complex to get right, but effective if used properly. If utilized properly, rewards can be powerful motivators because people tend to repeat behaviors that produce positive consequences and reduce those that yield negative consequences. That said, health campaigns that use incentives like money or other extrinsic rewards to perform a desired health behavior (such as offering people cash to lose weight) typically fail. Rewards should generally have a component that is immediate, like making mask wearing fun for children, in addition to a longer term albeit more nebulous component that makes people feel good because they believe their personal actions have contributed to the safety of their community.

Health campaigns that use incentives like money to perform a desired health behavior typically fail

For example, at the end of each school week, a principal can announce that because all the students and teachers practiced COVID-19 mitigation strategies consistently and correctly, the school was able to function yet another week without any new cases. This recognition acts as a reward to students and teachers who feel like they are doing their bit to keep the community safe.

These are just a few insights from behavioral science that the next administration can deploy to begin undoing the damage of the last ten months and regaining global public health credibility at home and abroad. This will not only require a strong, coordinated national strategy and collaborative implementation, but also a strong focus on science and on changing the way people think and act so that the United States can lead "not by the example of power, but by the power of our example."