A variety of sources have reported that the Chinese Government masked the severity and nature of the COVID-19 outbreak in the first weeks after it was detected. The World Health Organization (WHO) was publicly castigated, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was criticized from within the federal government, for not being able to either obtain independent information or to coerce the Chinese officials into sharing the information. This seems very political and related to the high stakes of this pandemic, but this problem of technical public health agencies unable to step-up and act aggressively when a partner fails to perform is as old as the institutions themselves.

Brilliant, driven health professionals from across the globe had left their usual jobs to deal with this terrifying outbreak

I had the distinct pleasure of working for the WHO in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak in 2014–2015. I say this not so much because I think the WHO is efficient or a model agency—but because brilliant, driven health professionals from across the globe had left their usual jobs to deal with this terrifying outbreak. In spite of those amazing colleagues, the WHO did not formally acknowledge that Ebola was in the country for almost three months after the first case was detected and confirmed. By August 2014, when the outbreak was finally declared, almost a thousand cases had occurred, including a couple among the WHO's staff. However, Ebola was hyper-political in Sierra Leone. It first appeared in the most opposition-voting district, and a member of parliament from that district immediately started spreading the misinformation that this was not an outbreak, but germ warfare by the government. The president and the minister of health were reluctant to acknowledge the arrival of the virus, and thus the WHO country director would not either.

The WHO is an agency comprised of member states, broken into regional offices, and the heads of those regional offices are elected by the member states. Because the member states tend to band together, the regional offices rarely contradict what a member state is saying. There are so many examples of the WHO not able to criticize a member state in the face of overwhelming evidence from independent sources. Some of the most prominent examples were its failure to say that genocide was happening in Darfur region of Sudan in 2003, that the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq had triggered hundreds of thousands of deaths, that famine was occurring in Northern Nigeria in 2016, and that Russia was behind the widespread destruction of medical facilities in Syria. Thus, the fact that the WHO was shockingly slow to acknowledge the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone surprised few. Having all of those amazing scientists I was working with on the ground was not enough to transcend the structure of centralized submission that exists within the WHO. And perhaps this is not all bad. More than 90 percent of everything the WHO does is in support of member states. The WHO helps them adapt new guidelines, improve their training and surveillance, and raise funds. Those tasks favor a nurturing partner, not a condescending know-it-all or a policing type partner.

More than 90 percent of everything the WHO does is in support of member states

In the United States, debates over "defunding police" have often raised a contradiction: Police are asked to deal with armed and violent criminals, and they are asked to deal with mentally ill, vulnerable people in desperate need of health-related assistance, but when they knock on a door, they are not sure which role they are being called to fill. In that case, it is abundantly clear how everything about an enforcement persona (e.g., gun drawn, voice loud and clear, messages unambiguous) is different from the support mechanism persona (e.g., gentle tone, mostly listening, perhaps sitting down to avoid seeming imposing).

As we look across institutions, the most successful ones tend to have separate policing and counselling or nurturing elements. For example, within the UN Agencies, groups like the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the weapons-inspecting United Nations Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) have monitoring and policing within their mandates: the ICAO investigates aircraft crashes while UNMOVIC was tasked by the United Nations from 1999–2007 to monitor Iraq's compliance with international weapon agreements. It is not by chance that both these agencies were structured with funding streams well buffered from the members that they inspect and monitor. While they make policy and advance guidelines, they are almost never tasked with member state training or nurturing activities. The WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), in contrast, mostly do nurturing activities, and seem rather poor at monitoring and policing partner failures.

Ethical Failures Up There with Tuskegee

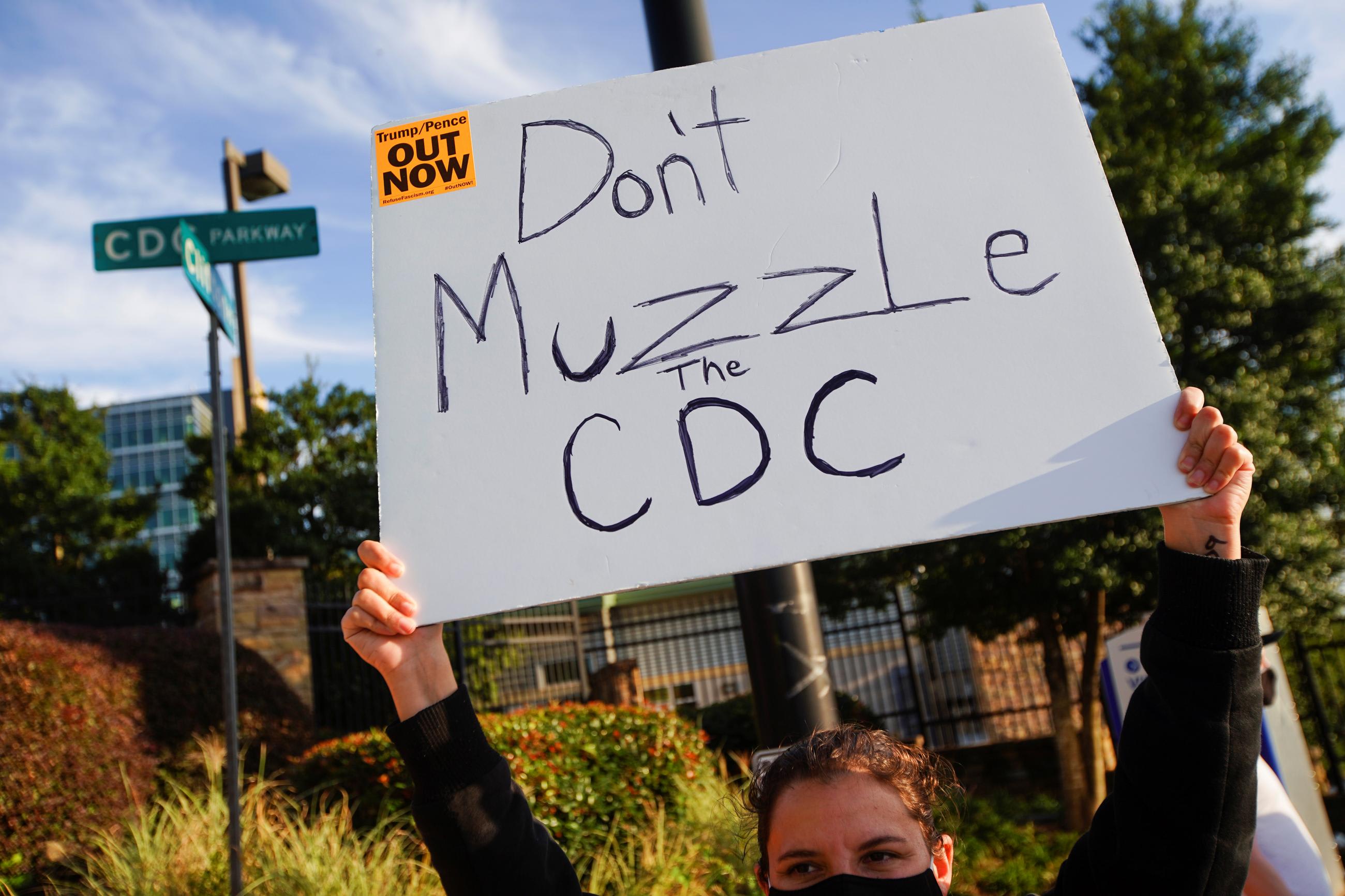

There may be no agency that has illuminated the dangers of mixing enforcement and monitoring activities during COVID-19 more than the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 1992, when I first went to work at the CDC and had a two-week orientation, one of the themes emphasized about the institution's culture was that the CDC was not an enforcement agency but an advisory and technical support agency. They did not want state and city health departments ever fearing them or concerned that information revealed to the CDC would later be used for enforcement actions. An extraordinary exception to this institutional cultural arose in 2017 when a federal rule was promulgated that gave the CDC the authority to prevent migration from certain places if that would reduce outbreak risks. While the CDC has been leading U.S. quarantine efforts for decades, this was almost always via guidelines and advisories that were enforced by other agencies. This legislation was passed with little fanfare, and most of my colleagues at the CDC never knew it had even happened.

Probably more than 99 percent of people who arrived at the border were not stopped by the new CDC order

On March 20, 2020, the CDC used this new authority to close the U.S. borders with Mexico and Canada to prevent the introduction of COVID-19. The order was very bizarrely written so that it only really applied to people who would have to enter "congregate" settings, and thus this applied almost exclusively to asylum seekers. Probably more than 99 percent of people who arrived at the border were not stopped by this order. Throughout the pandemic, Mexico had far less COVID-19 incidence than the United States. As a disease control measure, this made no sense and was widely protested by public health professionals. ProPublica reported how this order was initiated and created by White House personnel and how scientists at the CDC protested vigorously, including Dr. Martin Cetron, director of the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, who refused to sign it. He was quoted as saying, "It's just morally wrong to use a public authority that has never, ever, ever been used this way. It's to keep Hispanics out of the country. And it's wrong."

In terms of public health institutional mistakes, this order was insane. It was not just a bad idea—it was such a bad idea as to be offensive to other future bad ideas that might become lumped in with it. Unquestionably, for decades to come this will be held-up as a colossal ethical public health failure by the federal government, right up there with the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which deliberately withheld cheap, available, and effective treatment from hundreds of black men in Alabama and allowed them to suffer for decades. And at the core, this image and credibility debacle arose because the CDC allowed itself to slip from its role as a nurturing advisory institution to become a legal enforcement institution.

Deliberately withheld cheap, available, and effective treatment from hundreds of black men

Tuskegee changed the face of medical ethics forever, and the CDC quarantine rule may do the same. In the months to come, as the lessons of COVID-19 are debated, digested, and learned, and as health departments and agencies assess their mistakes, it will serve us well to remember the need to separate those nurturing and enforcement roles. We should structure our institutions to achieve their goals, and this will only come at the cost of the political forces surrendering some of their power. Creation of mission-protection mechanisms is never easy, but we see the logic of having courts and executive branches of Government separate or industrial inspectors employed by the government and not the industry in spite of the cost and inefficiency of that division of authority. Thus, with a death toll equivalent to the 9/11 attacks each week continuously for more than eight months, if we cannot correct these institutional structures or create separate effective monitoring counterparts for entities like the WHO and CDC now, when will we ever do so?