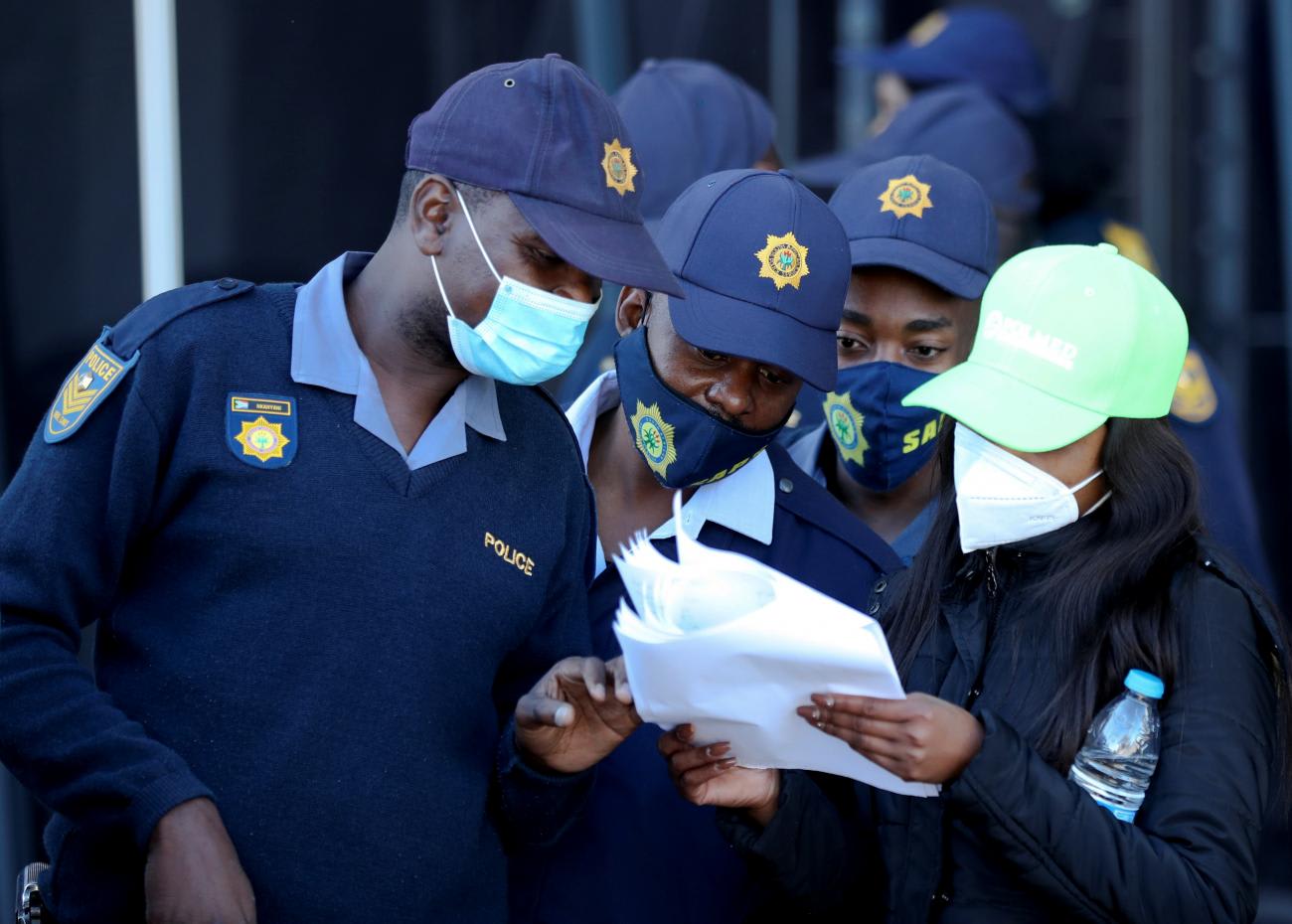

As countries in Africa race to access vaccines, treat a growing number of COVID cases, and negotiate lockdowns, global health experts and leaders are expected to convene for a special session at the World Health Assembly in November to deliberate a new global framework for the control and prevention of future infectious disease outbreaks.

But November is months away, and as Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), said earlier this year, "The world cannot afford to wait until the pandemic is over to start planning for the next one."

Africa's dependence on others, especially for essential diagnostic supplies and medicines, leaves it fragile

He has urged countries and global stakeholders to support the European Council-led proposal for an international pandemic treaty that would "foster a comprehensive, multi-sectoral approach in order to strengthen national, regional, and global capacities and resilience to future pandemics." While this is a worthy objective and such regulations for international health could strengthen global health security, including trade, transportation, and the environment, and could increase access to medicines—especially for developing countries during emergencies—in practice, it may not guarantee a unified or equitable response in the event of another outbreak. We have witnessed a failure to sustain multilateral partnerships and agreements during the COVID-19 pandemic. Africa's dependence on others, especially for essential diagnostic supplies and medicines, leaves it fragile.

As consultations gain momentum among global stakeholders, countries in Africa need to attain their own national resiliency plans, as well. African Union (AU) leaders should reflect critically on how to strengthen the part of their bureaucracy that effectively responds to health emergencies and how those strengths could be leveraged to bolster preparedness, especially when it comes to access to medicines and vaccines for noncommunicable and infectious diseases that are essential to improving health outcomes in Africa. Along with these efforts, they must push for equitable distribution and a timely sharing of new technologies, including data on pathogens, specimens, and genome sequencing.

Through an earlier joint continental strategy for COVID-19, the AU (via the Africa CDC-led response) successfully birthed several initiatives aimed at consolidating access to therapeutics and diagnostics. These include the Partnership to Accelerate COVID-19 Testing (PACT)—a collaboration which has enabled 43 countries that previously lacked testing capacity to diagnose the SARS-COV-2 virus. This was closely followed by the curation of the Africa Medical Supplies Platform (AMSP), which through a shared effort with the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), enabled pool procurement of personal protective Equipment (PPE), vaccines, and other essentials at a fair and fixed rate among member states. And more recently, the AU and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) launched the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) which is expected to help expand local vaccine production from 1 percent in 2021 to 60 percent by 2040. Still, scaling up of PAVM could face several bottlenecks. Notably, there is a decentralized regulatory environment for pharmaceutical commodities among member states that could hinder a safe and efficient introduction of COVID-19 vaccines. This same issue could also hamper economies of scale and consequently, the ability to compete with markets operating at a lower cost as countries in Africa embark on the implementation of a continental free trade area.

Now, two years after the adoption of a treaty for the establishment of the African Medicines Agency—a specialized institution of the AU focused on harmonizing regulatory functions among states' parties and African regional economic communities—only a handful of states have ratified it. Therefore, as calls for a global pandemic treaty increase, AU member states once again must take decisive action to consolidate regional institutions by ratifying existing treaties that are crucial to strengthening their capacity to respond to potential outbreaks. The African Medicines Agency treaty endorsed by the Bureau of Heads of State and Government in 2019, provides a unique opportunity to further streamline regulatory systems across the continent. Margaret Agama-Anyetei, Head of Health, Nutrition, and Population at the African Union Commission, said last year, "Instead of talking to eight regional economic communities or 55 countries, there would be one organization speaking on behalf of the continent."

A centralized regulatory authority in Africa could help curb a growing cross-border market of unregulated medicines

Aside from this, as countries in Africa become more integrated economically, prompting an increase in movement of goods and services, including medicines and other pharmaceuticals, a centralized regulatory authority could aid in curbing a growing cross border market of unregulated and fake medicines currently in circulation in Africa. Between 2013 – 2017, 42 percent of all counterfeit drugs were reported in the WHO African region. Similar issues have been reported for COVID-19 vaccines. By leveraging existing initiatives such as the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum and the Africa Regulatory Task Force, the African Medicines Agency could help coordinate and share information among national regulatory authorities, preventing thousands of premature deaths from substandard medicines.

Another impactful but less visible role that the African Medicines Agency could play is to help rebuild trust during and after a health crisis. This has become imperative amidst a pervasive distrust in pharmacological interventions, owing to a history of exploitation in medical trials and earlier research carried out in Africa by some foreign institutions and organizations. Notable among many examples, was a trial conducted for an unregistered drug, Trovan, by Pfizer, during a meningitis outbreak in Kano State, in northern Nigeria in 1996. It was a tragedy which later led to the death of eleven children. It has led to COVID-19 vaccine skepticism.

Complicating the issue further, recent reports of a risk of a rare clotting disorder, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), associated with both the AstraZeneca and Johnson and Johnson vaccine. These are two major vaccines in the COVAX portfolio which countries in Africa are relying on. Even though the Africa CDC has reassured member states of the safety and efficacy of these vaccines, persuading individuals and communities who were previously exploited could be an uphill task.

Apart from coordination of ongoing regulatory systems, providing guidance, and fostering reliance and regulatory harmonization across the continent, the normative role of the African Medicines Agency could be a vital tool in engaging these communities as mirrored in its counterparts elsewhere.

The Africa Union has appointed a special envoy—Michel Sidibe, a former Executive Director of UNAIDS—to help garner political support for the ratification and rapid launch of the African Medicines Agency. The ability of member states to act—to go beyond rhetoric—would not only be fundamental to the effectiveness of global public health practices and interventions, but is also essential for the new public health order in Africa. This is particularly pivotal as preparations, negotiations, and consultations for a global framework for control, prevention, and protection against future pandemics gathers political momentum.