Although death is inevitable, most people do not discuss it until it is at their doorstep. The current health-care system in the United States prioritizes overmedicalization, as Rebecca Blackwell puts it.

Blackwell, a research specialist at the Moffitt Cancer Center and an adjunct professor at the University of South Florida, said that "death used to be something we prepared for. It was done at home."

Following a medical boom in the 1960s and 1970s, more patients began dying in hospitals—and to some, this type of life-prolonging care felt akin to a loss of autonomy.

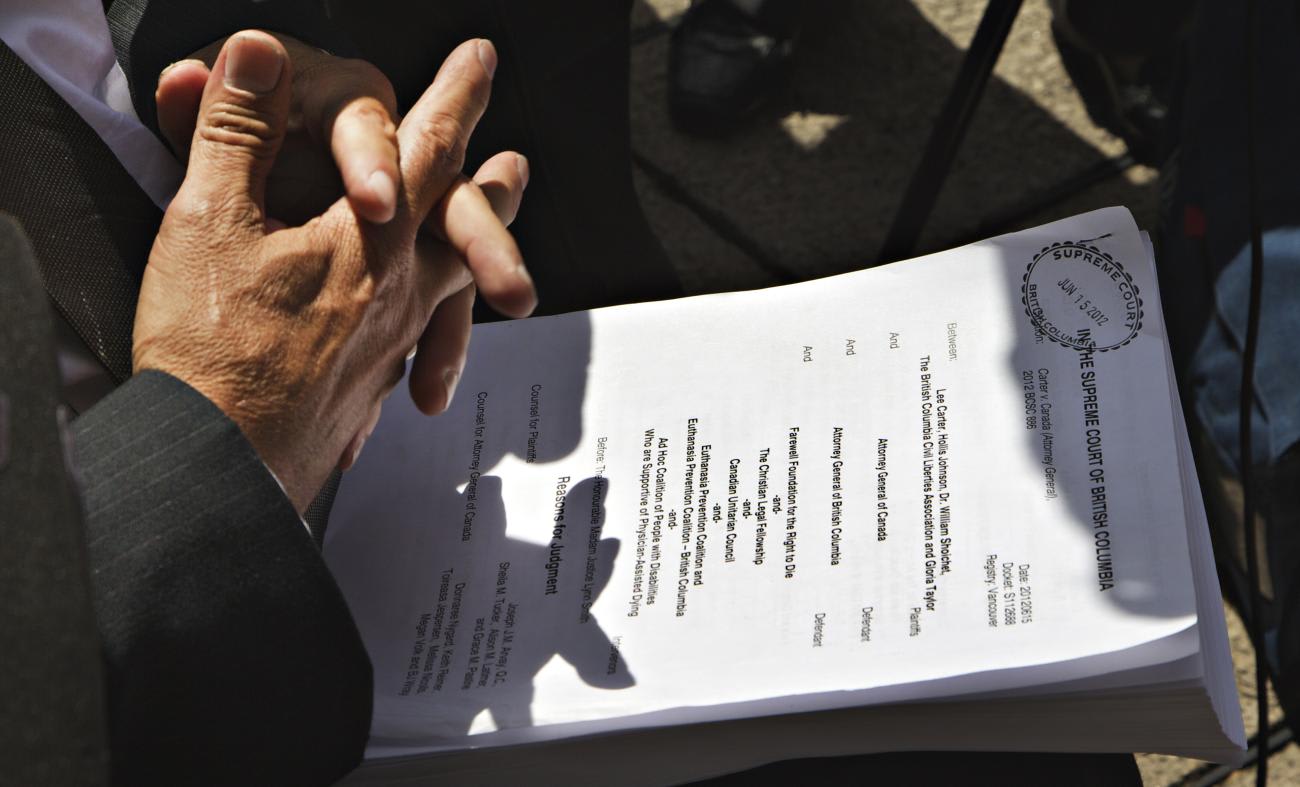

Assisted death—a palliative care option that allows terminal patients the choice to die—has slowly picked up pace around the world. Most recently in mid-October, the United Kingdom (UK) proposed a new bill to legalize assisted death for terminal patients. If passed, the bill will likely undergo scrutiny to ensure that stringent safeguards are instated, precautions even more rigid than similar laws elsewhere in the world.

Its parliament isn't set to vote on the bill until November 29, but the conversation around assisted dying and its ethics has been under way for decades.

For me, that's the power of euthanasia or assisted—that there is a very defined time slot for closure of life

Luc Deliens, End-of-life Care Research Group

Clinicians and policymakers are concerned about the steady rise in assisted death cases and the potential door that legalization could open for vulnerable people, such as those with disabilities or severe psychiatric disorders. Part of that rise is attributed to an aging population, a recent preprint study reporting that the number of euthanasia cases in the Netherlands has risen simply because the population of older people is increasing.

But it's hard for physicians to shake the fear that they could be inadvertently killing someone without a solid basis.

Legalization and Acceptance Steadily Increase

Assisted dying, sometimes known as euthanasia or assisted suicide, is a medical process during which a physician either administers or prescribes a drug that enables the patient to pass away quickly. With this procedure, the length of dying can last only a few minutes as opposed to months or some unforeseen time frame.

"For me, that's the power of euthanasia or assisted—that there is a very defined time slot for closure of life," said Luc Deliens, a professor of palliative care research with the End-of-life Care Research Group in Belgium. Deliens added that part of the value in this procedure is granting a patient the opportunity to prepare for death when they typically would not be ready. He believes that assisted dying often aligns with palliative care options such as hospice as well.

Five European countries have legalized medically assisted dying: Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland. Portugal decriminalized euthanasia as of 2023, and France just proposed an "aid in dying" bill earlier this year. Two Latin American countries permit assisted death: Colombia, where medically aided dying has been protected since 1997, and Ecuador. Voluntary assisted dying is legal in all Australian states save the Northern Territory, although the country's law comes with strict eligibility criteria, and diagnosis of an advanced or incurable terminal illness.

In 10 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, medical aid in dying (MAID) is currently authorized as an out-of-pocket expense, and another four are considering such measures. The oldest authorization began in Oregon in 1997—a state that in 2022 also ruled it unconstitutional to withhold MAID care for patients who do not live in Oregon but travel there for the procedure. Medical assistance in dying is also legal throughout Canada and Quebec, via euthanasia or self-administered with a clinically prescribed drug.

Dying voluntarily is not exclusive to Western societies. Medical ethicist Atsushi Asai has written calls to action imploring the Japanese government to consider the sociocultural norms around euthanasia and develop laws that would "enable those who sincerely wish to die to do so in a better way." According to his research, several cases of assisted dying have already occurred across the country despite the lack of legal protection. Asai suggested that the culture is shifting as more Japanese people grow accepting of assisted dying to protect a patient's agency, and in this respect it is better to proactively discuss substantive laws that address a voluntary approach to death.

Other East and Southeast Asian countries are opening similar dialogues on the right to die voluntarily. For years, Taiwanese legislators have debated physician-assisted dying with lackluster results—a lack of legislation that pushed a small organization of Taiwan doctors and volunteers to "quietly help the terminally ill access assisted suicide" by sending them to Switzerland where it's legal, according to Taiwan News. In South Korea, more terminally ill patients are choosing to opt out of life-prolonging medical treatments, a method known as passive euthanasia. Active assisted dying is still illegal there.

Who's Eligible for Assisted Death and Who Does It?

Across nations where it is legal, the basic parameters behind physician-assisted death look similar. In most places, the patient must be older than 18 and consult with more than one clinical care team or committee prior to approval. Assisted dying must also be requested voluntarily and with a sound mind—a mental state that is verified by clinical psychologists with assisted dying training.

Depending on the country, a specific diagnosis is not needed. Canada, however, states that the medical condition must be "grievous and irremediable." In the United States, the diagnosis must be terminal with a life expectancy of 6 months or less—and the patient must be able to take the drug without external assistance.

Such safeguards are put in place to effectively prevent patients from acting unwillingly or before they can no longer make health-care decisions alone. In all cases, patients have a right to change their mind at any point, even after the prescription is filled.

Knowing who has opted for physician-assisted death and why has always been difficult information to acquire. A 2021 study conducted by the End-of-life Care Research Group evaluated the frequency of physician-assisted deaths throughout Canada and European countries where the practice is legal. In Belgium and Switzerland, euthanasia accounted for 2.4% or fewer of all deaths in either country—or about 1,000 and 2,600 people respectively. That number is around 4.5%, or roughly 6,500, for the Netherlands, and less than 1% (11) for Luxemburg. About 2,600 or 1.1% of all deaths in Canada were due to MAID.

Between 1998 and 2020, MAID accounted for fewer than 1% of all deaths in U.S. jurisdictions where the practice is legal

In the United States, tracking MAID is extremely difficult, according to Elissa Kozlov, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor at Rutgers School of Public Health. Not only does each state collect different information for their individual reports, but a centralized database of MAID prescribers does not exist. Nor is MAID listed as a cause of death on death certificates. Because of that, "there's been almost no research," Kozlov said. "And there just aren't that many of us studying this."

Still, Kozlov and her team were able to aggregate some data pulled over a 23-year period. They found that between 1998 and 2020 roughly 5,300 patients died by MAID and an additional 8,400 received a prescription but death was not confirmed. Overall, she noted, every year MAID deaths accounted for fewer than 1% of all documented deaths in each state.

"MAID deaths are the lowest probability. Very few people are using this [option]," Kozlov said. "The reality here is that because of how the laws are written, it's pretty complicated to pursue MAID." Kozlov added that despite many ethical challenges to physician-assisted death, the data simply does not match the reservations.

Regardless of country or state, Deliens' and Kozlov's separate research say that the most typical diagnosis a patient has while considering physician-assisted death is cancer. Other common conditions include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or a combination of several prognoses, and most are related to terminal physical illnesses. Patients tend to be at least 65 years old. These results, coupled with other data from Europe, suggest that the patients most likely to pursue physician-assisted death are much older people with terminal illnesses, not necessarily populations with disabilities or severe mental illnesses.

Contentious Conversation Around Access

In Canada, doctors worry the scope of MAID may be getting too broad, allowing people with unimaginable pain, severe depression, and nonfatal medical disabilities to be eligible for MAID. According to the Associated Press, "doctors and nurses have expressed deep discomfort with ending the lives of vulnerable people whose deaths were avoidable."

The discourse in Canada mostly revolved around patients who are young, disabled, lonely, and poor in a system that could easily take advantage of their circumstances and offer early death as a way out. "The fear is also there because the disability community feels they are underserved by the medical system as a whole," said Blackwell. "It's such a struggle for them to just receive medical services."

Blackwell explained that some disabled people feel that they are at heightened risk when physician-assisted death is legalized and potentially extends beyond its intentions. Others raised concerns about the opposite: fearing the laws may be ableist in their terminology, prohibiting terminally ill disabled patients from going through with MAID.

"It's a conversation about individual freedom and autonomy on the one hand," Blackwell said. "And then that same argument is flipped on its head by the disability community saying, 'I don't have access to what I need, so I have no freedom.'"

The people who are pursuing MAID are overwhelmingly non-Hispanic white, older patients with a cancer diagnosis

Elissa Kozlov, Rutgers School of Public Health

However, the unease behind vulnerable patients being pushed for physician-assisted death is not backed up by the data for MAID. Kozlov and her team found that of all recorded United States MAID deaths and patients who received a prescription, the vast majority were patients from "the most privileged populations." Based on her work, Kozlov had discovered a "pattern emerge that the people who are pursuing MAID are overwhelmingly non-Hispanic white, older patients with a cancer diagnosis, and have at least some college education," she said. The majority were men as well.

Blackwell added that "it's not something that's very prevalent at all in many nonwhite communities, although the organizations advocating for physician-assisted death are beginning to incorporate race in their discourse."

As it stands, physician-assisted dying is limited to select countries and states. Experts encourage open dialogues with not only clinicians and legislators, but also the narratives of patients and their families.

"If you don't do it properly, you create a lot of frustration and tensions not only between health care providers, but also between the health-care providers and the patients and the families," Deliens said. "It's very complex."