Women make up nearly 70 percent of the global health workforce, but 75 percent of leadership positions are occupied by men. As Women's History Month draws to a close, Think Global Health spoke with three women who are leaders about their experiences in global health leadership.

Maseretse Ratia, Program Officer at the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in Lesotho

Maseretse Ratia says her work educating young people about sexual and reproductive health is influenced by her own rural upbringing.

When she was a child, her role model was her mother, the principal of the local primary school in Lesotho, where students were very poor and often dropped out. "My mother was a super woman," she said. "I've seen her take a stand in assisting the community to send children to school, in supporting them to apply for scholarships, in helping a family get an adolescent girl who was married off back to the family."

During Ratia's secondary education at a school run by Sisters of Charity, her teachers exemplified qualities of leadership and discipline she wanted to absorb. After graduating from the National University of Lesotho and beginning her own career as a school teacher, she saw firsthand the vulnerability children face. That led her to a job with the nonprofit Help Lesotho, which provides life skills training and mental health care in rural areas of the country.

Since joining UNFPA at thirty-one, she has helped the Lesotho government decide how best to respond to the challenges that young people face, including early and unintended pregnancies and child marriages, "which prevent girls from reaching their full potential and becoming the future leaders."

She designs and implements programs that educate girls and boys on sexual and reproductive health and rights, gender-based violence, and HIV. She envisions a society where children are protected from all forms of sexual exploitation and girls can pursue studies "that they love, not courses that are being suggested by the community," she said.

Girls ought to be liberated, independent, and able to voice their opinions instead of being consumed by meeting societal expectations, she said. Girls "who still respect their culture, their elders, the way we are raised as children, but who are out there and facing the challenges of the world like nobody's business." She added, "I want girls to be super girls."

To increase female participation in global health leadership, Ratia believes, education needs to be equally accessible for boys and girls and women also need to be empowered. UNFPA Lesotho, where the majority of staff are women, gives everyone an equal opportunity to work, express their opinion, and make decisions, she explained.

UNFPA has provided training, webinars, and leadership programs to assist her and colleagues in becoming better leaders. She believes that organizations should make a deliberate decision to appoint women to leadership positions and provide them support and mentorship.

Ratia hopes to become a country representative one day. In the meantime, she continues to learn, seeking to better understand the world beyond Lesotho, the challenges it faces, and the innovative strategies being used to resolve them.

"So it is within me, but I need to be given an opportunity to also to exercise such powers," she said, "instead of being judged on the basis that I'm just a woman."

Michele Barry, Director of the Center for Innovation in Global Health at Stanford University

While attending Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York not long after the Vietnam War, Michele Barry stumbled upon the world of global health. "I was taking care of a lot of refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, and I realized that I did not know very much about their tropical diseases," she said. To provide them better care, she decided to get a degree in tropical medicine.

She has since held various leadership positions, including as president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine.

In her decades in medicine and global health, Barry has seen more women join the field, but most are still left out of positions of leadership. Women are underrepresented — as heads of state, in global health leadership, and particularly in health agencies in the low- and middle-income countries, Barry explained.

"One of the things I was worried about when I started my career is whether I could do global health and still have a family," she related. "I wish someone had been able to role model that for me, and I hope I do role model that for young women now."

Barry's children sometimes accompany her when she travels abroad for work, where they encounter a far more enriching learning environment even if they have missed some school. She advises other women interested in global health leadership that family responsibilities need not derail their professional development. An expectation that women must take on the bulk of caretaking plays a role in why many midcareer and senior women leaders drop off.

"Women who are early career don't really have that much of a gap, but later in their career that leadership gap widens," she said. "That's why I'm working very hard to give women leadership skills so that they can progress and get through that stuffed pipeline [midcareer when the gender gap widens]."

Both unconscious and overt bias play a role in a dearth of personal and professional resources, such as mentorship, offered to women. She has used her position to promote and uplift other women leaders.

"I've certainly had microaggressions that have been pushed toward me, where I've been excluded from conversations that are important," she said. "It has happened recently, around a new school we're developing at Stanford, where I feel that I need to have more input into. I have called this out."

She also criticized manels — panels exclusively with males, despite plentiful qualified women who might have participated — as another common demonstration of how women are overlooked. Some leaders, such as former NIH head Francis Collins, have pledged not to participate. "If men allies are interested in that, they [can] sign the pledge," she said.

Roopa Dhatt, Executive Director and Cofounder of Women in Global Health

Roopa Dhatt immigrated to the United States from India at age five but frequently went back to India visit her grandparents. One summer, when she was nine, she became severely ill, had emergency surgery, and nearly died. After a month in the hospital there, she returned to the United States; the contrast of health systems was palpable even to her as a child. "It just never made sense to me that we could be on this one planet and have such wide inequalities, especially in health."

Interested in addressing health inequities, she became a hospitalist, but her passion was for global health. In 2015, after connecting with three other women interested in advancing women's leadership in global health, they hatched a plan to go to the World Health Assembly.

She recalled the group saying, "What we really need is collective action, so let's launch a movement that brings women and all genders together to advance gender equality and global health leadership."

The nonprofit they founded, Women in Global Health, now has more than forty-seven chapters around the world and brings together communities of women leading locally from all backgrounds and at all levels of seniority.

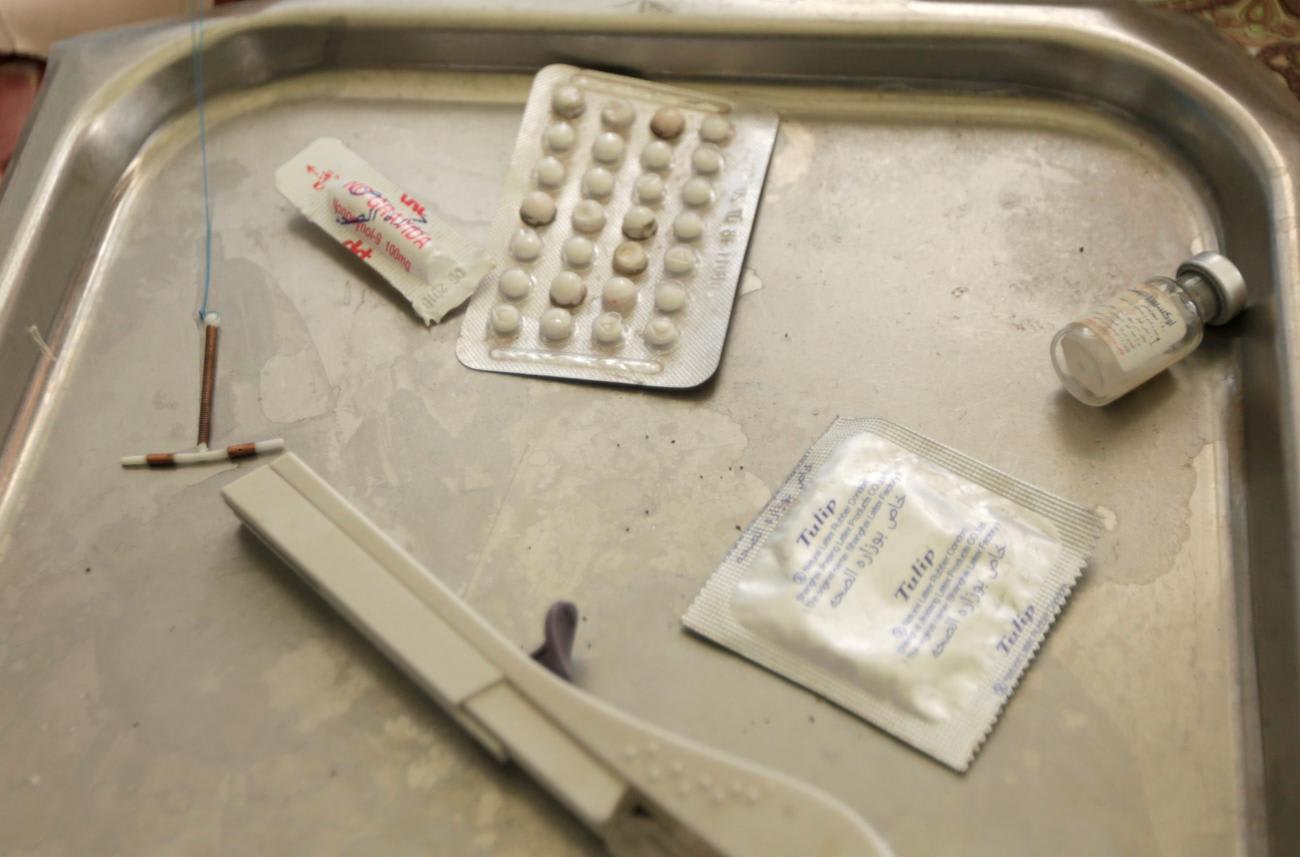

Because of the vast underrepresentation of women in global health decision-making, what seem like gender-blind policies often have inequitable consequences. For example, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, family planning and maternal neonatal care were some of the first services to be disrupted and disregarded. Many women couldn't access birth control and an entire scope of sexual reproductive health services were paused.

In a World Health Organization survey of 105 countries, nearly 70 percent reported that family planning services were disrupted early in the pandemic.

"If women were on the highest levels of COVID-19 decision-making teams in equal numbers, they would not sit quiet and say, well, pregnancy stops during pandemics," Dhatt related.

This was particularly problematic because women found themselves in greater need of services, not less. Some countries observed a 30 percent increase in gender-based violence because lockdowns kept women and girls at home.

Early in her career, when Dhatt was elected president of the International Federation of Medical Student Associations, she had to navigate gender bias.

"I found a lot more resistance, less uptake, a lot more questioning about my leadership abilities, and my decision-making process and being often labeled as an emotional leader instead of a rational leader," she said, all stereotypes that women in power constantly deal with. "We often say we walk a tightrope, and I felt what it meant to be walking a tightrope for the first time so intensely."

Her colleagues have also experienced a range of barriers, many of which continue to go unaddressed, and, as in many fields, women across the health sector face bullying, sexual harassment, and sexual exploitation.

Women health workers around the world feel "unsafe to go to work and take night shifts, along with facing advances from male supervisors and an entire range from sexual harassment," as documented in a recent report from Women in Global Health.

To make matters worse, the gender pay gap in the health sector is among the worst of any sector.

"The poorest women subsidize health all around the world," Dhatt said. Even in high-income countries, the pay gap between women and their male colleagues is larger than in almost any other sector.

The WHO found that in the health sector women are paid 24 percent less than men globally—even controlling for age, education, and experience. When women do ascend to leadership positions, Dhatt said, they have shorter windows to be viewed as leaders.

"They're either too young or too old," she explained. "And so it's more difficult for women to have lifelong leadership roles where they are valued or viewed as leaders at the highest level."

When women don't have equal leadership in global health, the field misses out on women's expertise, Dhatt said, especially women working on the frontlines.

"Viewing (women) only as vulnerable populations or recipients of care means that they're just not going to have the same level of ownership of those solutions," she observed.