In November 2022, as zero-COVID protests were simmering across China, videos circulated of a young, female voice speaking to a large crowd at Tsinghua University. Sensing her nervousness, fellow students yelled, "Don't be afraid!"

A STEM-focused school renowned for churning out the future Chinese Communist Party leadership complete with an Institute for Xi Jinping Thought, my alma mater Tsinghua is one of the last places I would expect a sizable zero-COVID protest to surface. The protest that formed in front of Zijin Canteen was utterly organic—no planning or coordinating among students in advance.

I spoke with the undergraduate student who inadvertently made global headlines when she stood in front of Zijin with a blank sheet of paper—a symbol of protest in China against censorship and control.

"I stood by myself for half an hour. Interestingly, those who first joined me were girls," she said. "I thought it would just be me, but then everyone else showed up."

This trend wasn't limited to the Tsinghua protests; many noticed that zero-COVID protests around China were largely led and dominated by women. This is unsurprising given that COVID-19 lockdowns in China disproportionately burdened women who culturally bear the primary responsibility for taking care of both children and the elderly and were at heightened risk of being locked at home with abusive partners. Tsinghua men, who largely benefit from the patriarchal status quo, were less likely to risk jeopardizing their privileges by voicing any discontent.

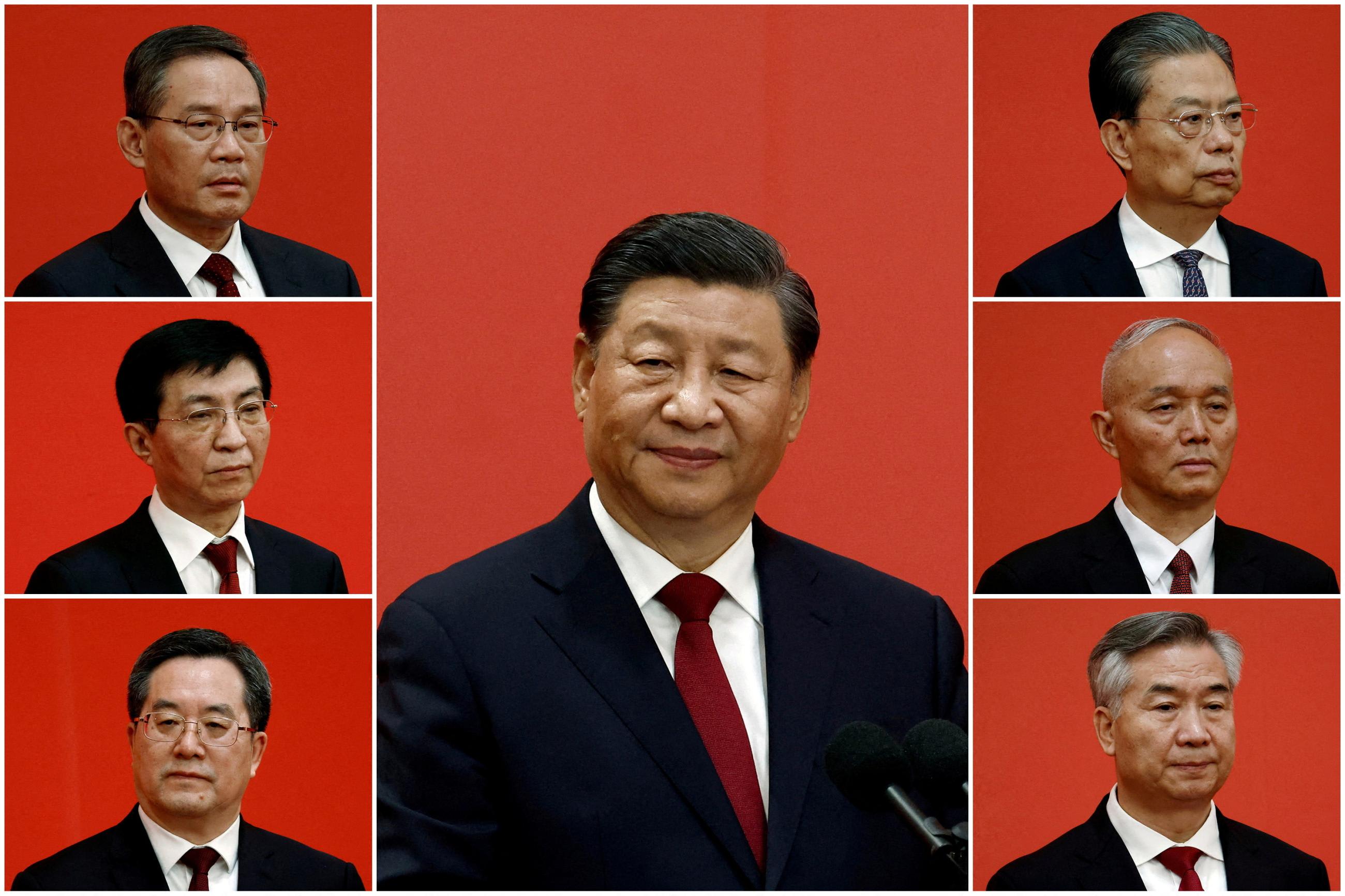

In a nation where the decision-makers are overwhelmingly male, "women rarely have the opportunity to make our voices heard," the Tsinghua student said. To reaffirm the government's lack of interest in female representation, Xi gutted the twenty-five-year-old tradition of having one female member in the twenty-five-person Politburo. The message was clear: women hold up none of this elite, powerful sky.

Throughout zero-COVID, as much of China was in various degrees of lockdown and people locked inside had time to ruminate over news and social issues, reports of violence and neglect became ingrained in the conscience of women across the country. Incidents such as the four young women in Tangshan brutally beaten for rejecting the advances of a middle-aged man and the woman in Xuzhou found chained like a dog to a shed in the dead of winter renewed calls to bring gender equality to the forefront of the national policy agenda.

All were constant reminders that for all the economic leaps and geopolitical bounds that China has made, women continue to bear the burden of inequality and gender-based violence. Still, the government does little to actually address the patriarchal foundation of these issues and often creates brute and shortsighted legislation that makes matters worse. For example, the 2021 introduction of the thirty-day waiting period to decrease divorce rates made leaving abusive marriages more difficult, as marriage rates continued to decline.

On New Year's Day 2022, because of zero-COVID protocols, a hospital in Xian rejected a pregnant woman and left her outside bleeding on a plastic stool as she lost her baby. In the month leading up to the reversal of zero-COVID in November, a woman in Hohhot committed suicide; voice memos circulated of her daughter begging the zero-COVID personnel to unlock the doors and send help to her mother. In response, Hohhot's Internet Culture Association released a commentary that her suicide betrayed "filial piety and motherly duties."

In light of the constant wave of zero-COVID lockdowns in recent years, the three-child policy introduced in 2021 to encourage an increase in birth rates has proved to be yet another out-of-touch piece of legislation. This year, headlines across the world rang alarm that China's population has decreased for the first time in sixty years. The aging population and expectations of women to take on the bulk of caring for the elderly could put greater strain on women's participation in the workforce and further decrease birth rates.

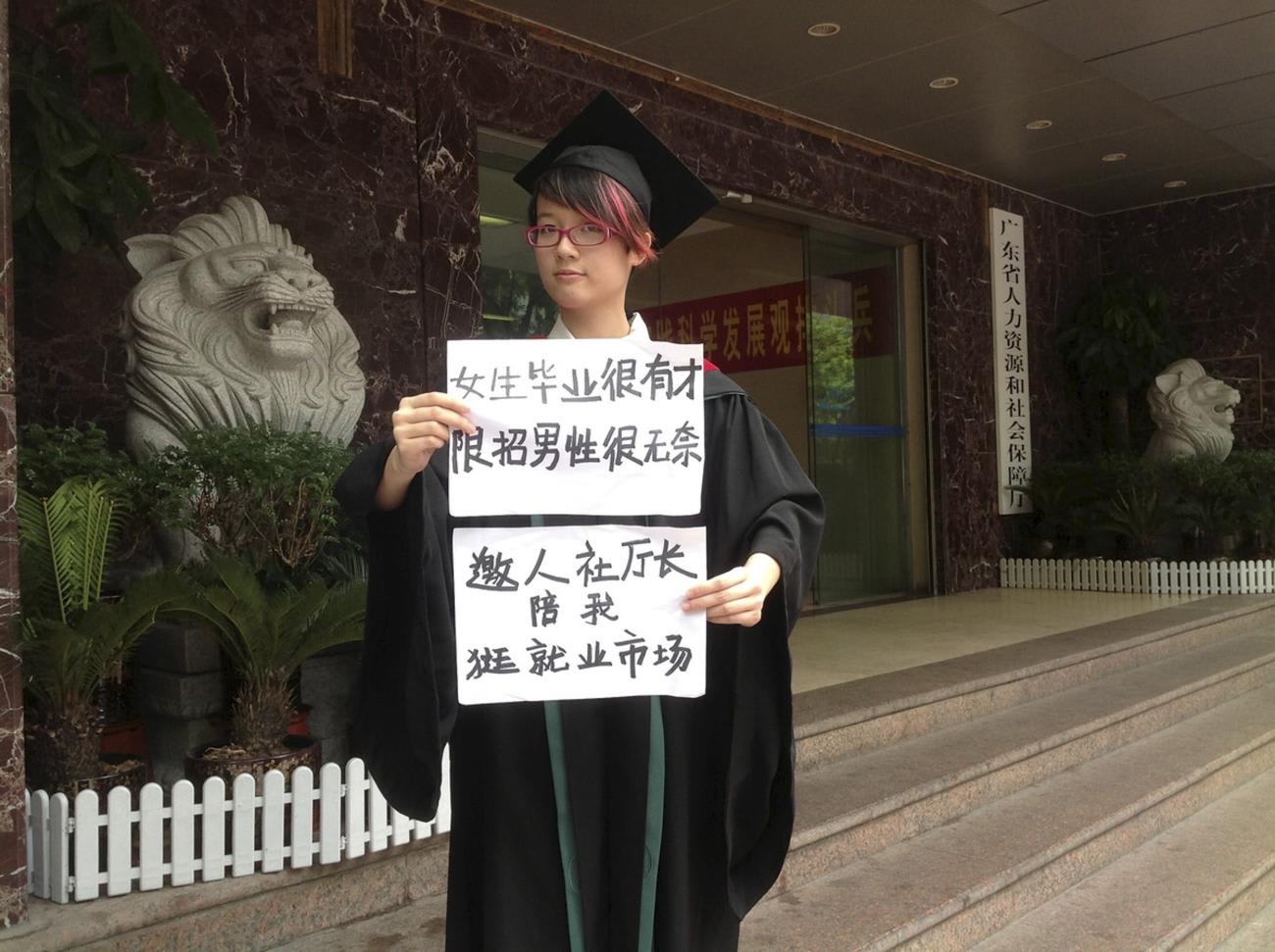

Yet China's policymakers do little to address the root of plummeting birth rates: decreasing gender equality, widening gender pay gaps, and worsening gender bias and discrimination in the workforce. Rather than recognizing the benefits of women gaining economic freedom and educational opportunities—such as how the seven million "leftover" single women in China, largely urban and well-educated, are some of the greatest contributors to China's economic growth — China's government sees single or childless women as the problem. Even as the birth rate plummets, the government continues to discriminate against single mothers.

In 2012, the year Xi came to power, China was ranked sixty-ninth in the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Index. Now, in 2023, it ranks 102nd of 146 countries. From 2012 to 2022, China dismantled the one-child policy and scrapped all fines for having more children than allowed. Even so, China's birth rate dropped from 1.8 in 2012 to an estimated 1.2 in 2022.

Only a patriarchal nationalist government with eyes closed and ears shut to women's struggles and hopes could somehow end up with a far lower birth rate than it began with when the one-child policy was in place. The question now isn't how China is going to institute policies to encourage Chinese women to have more babies. The task at hand is adapting to the demographic changes. This could mean shaping their economy to rely less on masses of cheap labor who are aging and not being replaced.

Zero-COVID policies have shown the world that the Chinese government can change course in an instant when the commitment is there. Why not put that energy toward rebuilding every institution to undo its patriarchal foundations? This would uplift women to their full potential—rather than pushing them out, devaluing them, or restricting them to one narrative at every opportunity.

My female classmates at Tsinghua, even though many may stay mum in their day-to-day lives about gender inequality, are not blind to national policies as they make their reproductive decisions, the trauma of zero-COVID being a factor for some time to come. As I think about the young woman who took the first stand in front of Zijin Canteen—politely and quietly, in the middle of the two entrance ways—I think of how China's current state is a stark reminder to the rest of the world that, when it comes to defending a free and just society, feminism and gender equality are a first line of defense.

"As women in China become more educated, the line for them to walk on and the parameters for their socioeconomic status becomes narrower," the Tsinghua student said.

In today's China, where discourse and actions that challenge the status quo are deemed too divisive, to do nothing and say nothing has begun to say everything. From the beginning of zero-COVID to its abrupt reversal and end, women in China have spoken.