Shortly after Hurricane Katrina, New York Times opinion columnist Maureen Dowd published an article that depicted New Orleans as "a snake pit of anarchy, death, looting, raping, marauding thugs." It was a familiar characterization of post-disaster society, with social order quickly disintegrating into fierce competition between selfish individuals. But is that really how humans respond to shared adversity?

This description of lawless chaos is what some might call a "disaster myth." Researchers at the University of Colorado investigated reports of looting after Hurricane Katrina and found that contrary to media claims, there was actually a decrease in crime compared to regular times. In fact, many citizens "went out of their way to help one another." This evidence suggests that the media often overemphasizes deviant behavior after disasters, while overlooking selfless acts.

This description of lawless chaos is what some might call a "disaster myth."

Jamil Zaki, a professor of psychology at Stanford University, has found that disasters typically lead to more generous behavior, what he refers to as "catastrophe compassion." Shared negative experiences bond people together and produce a heightened sense of solidarity, empathy and emotional connection, which increases cooperative behavior. This phenomenon is consistent after hurricanes, wars, terrorist attack, and now, a pandemic.

Highly publicized accounts of people hoarding toilet paper, or gathering for beach parties in open defiance of legal restrictions meant to protect vulnerable people, promote the belief that every person is for themselves during the pandemic. But generosity may have actually increased.

This theory is supported by a 7.5 percent rise in charitable giving in the first half of 2020, according to an analysis of 2,500 non-profits, many of whom experienced a substantial increase in small donations and new donors. It is also reflected in the growing use of "mutual aid spreadsheets" that community volunteers have used to organize help for vulnerable neighbors. And it shows in how billions of people have social distanced to protect public health, driven largely by concern for others. These constitute some of the largest acts of cooperation in history.

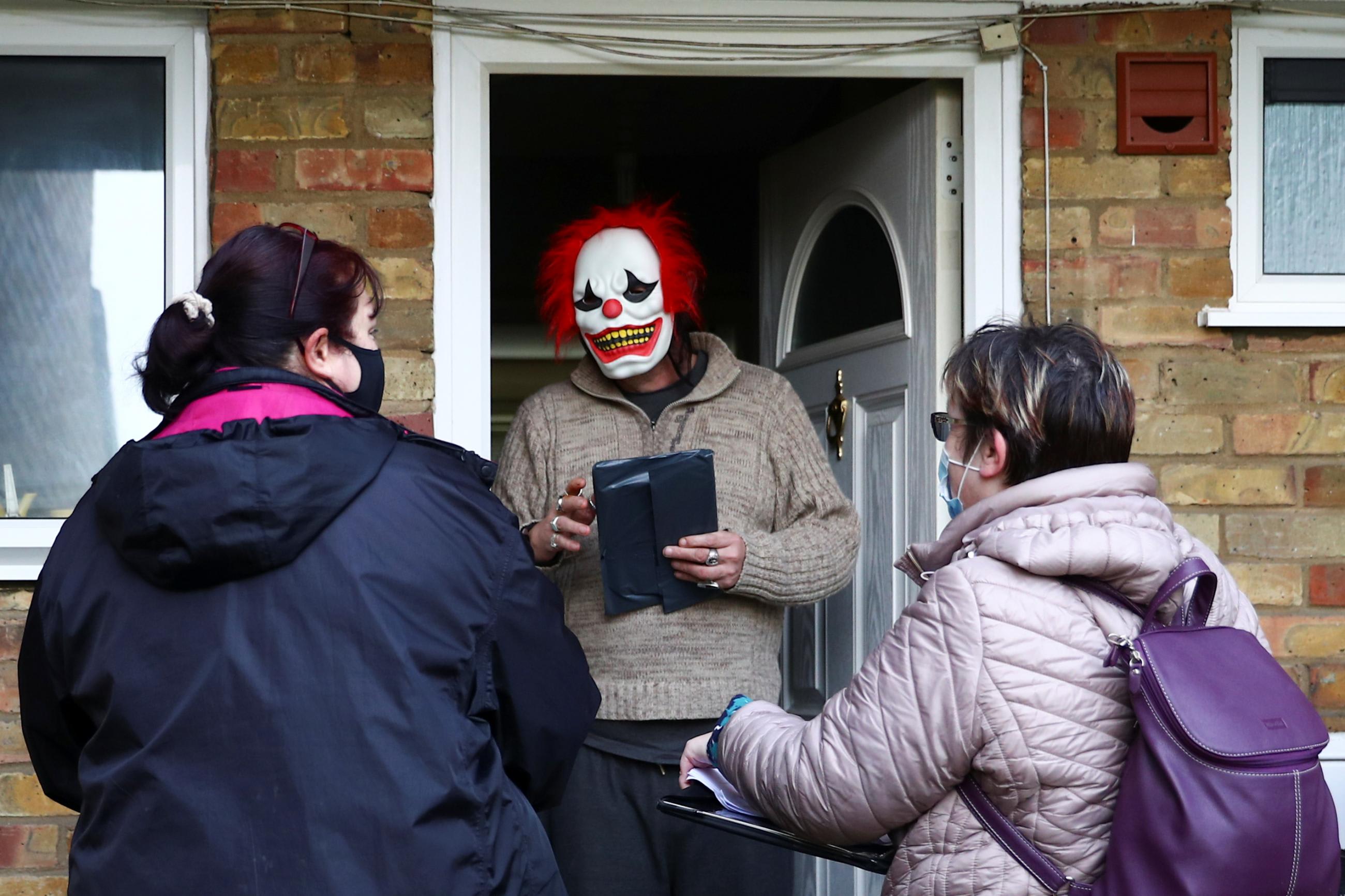

Although many people are predisposed to act generously, they still expect others to act selfishly. Rebecca Saxe, a professor of cognitive science at MIT, studies how people reason about the thoughts and feelings of others. In March 2020, she and her partner Daniel Nettle asked 400 people in the UK to predict how their fellow citizens will respond to the pandemic. The majority of respondents expected others to be selfish and thought the pandemic would lead to conflict and distrust, instead of solidarity.

Saxe says that this intuitive theory of human behavior could help us prepare for worst-case scenarios. But the predictions are largely inaccurate, and may create a systematic gap between our expectations of others in a disaster and how they actually act, leading to a pessimistic bias about human behavior.

People are more likely to be generous in times of shared adversity, in part because collaboration confers an evolutionary advantage. "We have this psychology of need-based helping that gets activated when we're dealing with uncertain kinds of situations," said Athena Aktipis, an associate professor at Arizona State University. In evolutionary models, enhanced cooperation after a disaster improves fitness because individuals can pool risk: like an informal insurance policy, individuals are more able to weather difficult situations together by sharing resources.

We have this psychology of need-based helping that gets activated when we're dealing with uncertain kinds of situations

Athena Aktipis, associate professor, ASU

"If we're in the zombie apocalypse, and we're the only two people left, I'm much better off if you stick around, and you're much better off if I stick around," Aktipis said.

This disaster psychology may enhance cooperative behavior, but what kind of cooperative behavior? Scientists separate prosocial acts into two categories: reciprocal acts that benefit others with the expectation of compensation, and altruistic acts without any expectation of repayment.

Associate Professor Lorenzo Lotti at the University College London conducted a study to tease apart how the pandemic affects these different types of cooperative behavior. Lotti analyzed the giving attitudes of 1,255 American citizens over the first two months of the pandemic. He gave them $4000 imaginary dollars to distribute to four hypothetical recipients: relatives, neighbors, the government, and anonymous individuals. Only the last group is considered an act of pure generosity, since the giver cannot expect anything in return. Lotti found that donations to anonymous individuals nearly tripled between March and May.

Lotti expects that donations were initially lower than normal due to high levels of unemployment among participants, but later surged due to the warm-glow effect, the emotional satisfaction of giving to others, which peaks as COVID-19 cases and pandemic-related anxiety rise. Lotti explained that strangers are in more unknown and potentially precarious positions than relatives and neighbors, so participants likely provide more support to strangers as perceived general risk to others increases. Participants may derive more emotional satisfaction as their donations appear more impactful.

Neuroscientists have found that charitable giving activates the mesolimbic reward pathway, a part of the brain that motivates pleasurable behaviors like eating and sex. These findings suggest that altruism is not a high-level moral faculty that suppresses selfish desires, but rather a basic, hard-wired pleasure. In fact, giving literally makes the giver feel warmer; researchers in Beijing found that participants who help out in a laboratory or donate to a charity perceive the ambient environment as physically warmer, suggesting an immediate internal reward to altruism.

While Lotti's study only measured hypothetical donations, this type of experiment has been found to mirror real-life giving behaviors, and may even underestimate them by removing social incentives, such as improving reputation or receiving repayment. His findings suggest that the pandemic increases altruistic behavior, at least initially. Over time, this increase in generosity may be eroded as COVID-related distress becomes more normal, awareness of others' suffering decreases, or additional financial strain reduces giving capacity.

Perceived interdependence and willingness to house a non-citizen in need rose in the first months of the pandemic and have remained high

"Across lots of disasters, in the first few weeks, people often are very much in a mindset of helping others, essentially working together to recover," said Aktipis. "But when you have chronic ongoing disasters, that can take a toll on people's capacity to help each other, too."

To test the endurance of cooperative behaviors, Aktipis has been collecting data on perceived interdependence and willingness to help others since the pandemic began. She found that while respondents reported an increased sense of interdependence with all of humanity, it didn't last past the first few months. Other measures of cooperation have persisted. Perceived interdependence with neighbors and willingness to house a non-citizen in need rose in the first months of the pandemic and have remained high. This shift may be attributed in part to more exposure to adversity, which can increase compassion for others – especially in the face of mass suffering.

"Having some shared awareness of the challenges that everybody faces is the first step to people being willing to pool risk together and establish mutual aid kinds of networks that can really help communities be more resilient," said Aktipis. The challenge is maintaining empathy and connection with each other after the initial shock of the pandemic fades.

"Even while humans are capable of great selfishness, they are also capable of true altruism," said professor of philosophy Samuel Rickless at the University of California, San Diego. We have a moral obligation, he added, to keep caring about each other: to wash our hands, wear masks, socially distance… But hopefully these small acts are also accompanied by a warm glow.