The world is pouring money into battling COVID-19 in Africa, but in the race to triage with stopgap solutions, we risk missing a critical opportunity. It's time to dispense with the well-worn, threadbare fiction that just because it's Africa, we have to settle for less. The health-risks today are undeniable on a continent of 1.3 billion people spanning fifty-four countries including many without basic health care.

Africa shouldn't be subjected to the 'soft bigotry of low expectations'

Former President George W. Bush

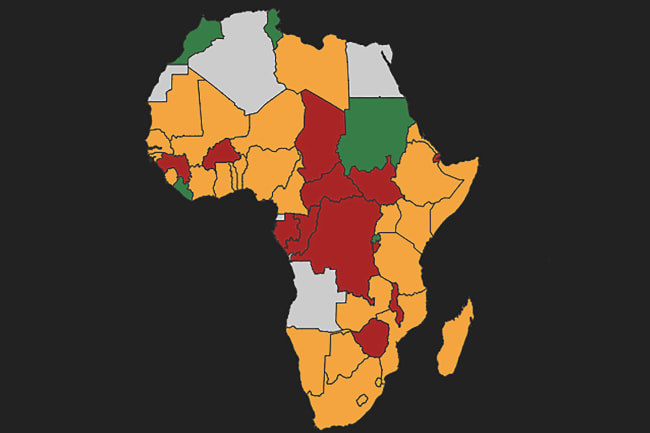

In sub-Saharan Africa, 41 percent of the population lacks access to clean water and soap, critical for the basic sanitation necessary to stop the spread of disease. The world is right to fear catastrophe on a continent that holds only two thousand ventilators across forty-one countries—including ten countries that lack any ventilators at all. There are only five thousand intensive care beds from Morocco to South Africa. But to quote an unlikely source, former President George W. Bush, Africa shouldn't be subjected to the "soft bigotry of low expectations," let alone colonial thinking. Millions of Africans need not be destined to die of COVID-19 or from the next pandemic. African governments and their partners can strive to build robust, resilient high-quality, equitable medical systems—and they can do it now.

I write from two perspectives that have influenced me greatly. On the one hand, I am a critical care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, where I've treated coronavirus patients with access to the best medical resources. I am also the head of Seed Global Health, a non-governmental organization that helps build training and human resource capacity in resource-constrained countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Previous public health investments on the continent have taught the world valuable lessons—and cautionary tales—that should be heeded.

Basic Health Systems and COVID-19 in Africa—by the Numbers

The world is right to fear for Africa, but not to subject it to the soft bigotry of low expectations

Starved of Infrastructure

In the 1990s, structural readjustment programs, required for countries to secure a loan from the International Monetary Fund or World Bank, ravaged the education, health, and social sectors across Africa. These requirements starved many countries of fundamental infrastructure needed to provide health and opportunity to a generation of workers.

The opportunity to make a much larger impact with a marginally larger investment

By the turn of the century, HIV had swept the world. The global community poured billions into treatment, redefining and expanding the concept of global health. Countries learned care could be delivered in the poorest settings, saving lives and building networks and systems to counter crippling disease. But in only targeting HIV and other specific diseases, many countries missed the opportunity to make a much larger impact with a marginally larger investment to scale up primary care networks—networks capable of addressing more than just the prevention, diagnosis and care for HIV but also ensuring safe births, tackling the growing epidemic of non-communicable disease and provided essential preventative care to all.

Instead, shining HIV centers of excellence were built. They now stand beside crumbling primary care clinics where old shelves strain under the weight of paper records.

Lessons of the Ebola Pandemic

More recently, the subsequent Ebola outbreak demonstrated the devastating effects of not having enough healthcare workers to recognize a pandemic, sound the alarm and mount a response. As a result, more than 28,000 people were infected and 11,000 died. The virus spread to ten countries, three continents and cost more than $53 billion to treat.

The economic and human cost tells only a portion of the story. Following the outbreak, disruptions to routine health programs have created the risk of tens of thousands of additional deaths– more than from Ebola itself – as health resources were diverted from primary care and vaccination programs.

These mistakes don't need to be repeated on COVID-19.

Ebola spread to ten countries, three continents and cost more than $53 billion to treat

Instead, countries should maintain focus on essential services and channel investments into bolstering their comprehensive health systems. Local leaders and governments must be equipped to lead the response and guide the plans, implementation, and strategy to meet the health needs of their countries. We should move away from donor-driven agendas. Investments should be aimed at training and retaining the full spectrum of health workers: doctors, nurses, midwives, community health workers, technicians, and ancillary staff.

Timelines need to change as well. It will take multi-year investments to create, transform, and strengthen health systems. These investments may not yield immediate gratification, or immediate results. But a systematic, long-term approach will allow countries to escape the limitations of the toxic trope that good enough is enough in Africa.

To escape the limitations of the toxic trope that good enough is enough in Africa

If we channel money and energy to support partner countries interested in building robust health systems, we'll finally be able to cover not just the last mile but extend the next mile. Broad and equitable health systems can finally be available in African countries—not just desperately needed, but closer within reach than the world yet realizes. Strive, don't settle.