First of its kind research published in The Lancet Global Health delivers one of the clearest warnings yet about the consequences of aid sanctions—not on autocrats or dictators—but mothers and children.

"Sanctions are an imperative tool to prevent or stop war. However, it's important that we understand how these measures work and their impact on local populations," said lead author Ruth Gibson, a postdoctoral fellow in Stanford University's Department of Health Policy.

The research seeks to fill a glaring gap in health governance, which is the absence of coordinated monitoring at the global level that tracks how any type of sanction harms health, at a time when more than 60% of all low-income countries are subject to them.

This gap persists despite a tenfold increase in sanctioning episodes since the 1960s and a growing pile of evidence that the most vulnerable civilians pay the price.

The team from Stanford, Drexel University, and the University of Washington analyzed 88 aid sanctions imposed on 67 low- or middle-income countries between 1990 and 2019. Aid sanctions are considered a more targeted and less aggressive measure of coercion than broader trade or financial sanctions.

Yet the Lancet study finds that even these measures have devastating consequences. The average cut during the study period amounted to $213 million in official development assistance and $16 million in direct aid to health annually.

As a result, the researchers say that infant, under-five, and maternal mortality rates rose by an average of 3.1%, 3.6%, and 6.4%, respectively. Given that a typical sanction episode lasts five years, they estimate that these patterns wipe out nearly 30% of improvements in child mortality and 64% of the progress in maternal mortality rates.

One of the authors, Stanford professor Gary Darmstadt, points to a dependency on fully functional systems as a reason maternal mortality was hit hardest: "For managing child illness, we've worked out approaches that can happen more at a community level, like giving life-saving antibiotics. Whereas if a woman is hemorrhaging, the only thing that will help is care from a skilled provider."

Darmstadt explains that as aid is pulled and a health system begins to deteriorate, supplies of critical goods begin to run out, equipment breaks down, and transportation to health facilities becomes harder.

"As a result, women seeking urgent care may suffer, and once they get to where care is provided, it is likely to be disrupted," Darmstadt said.

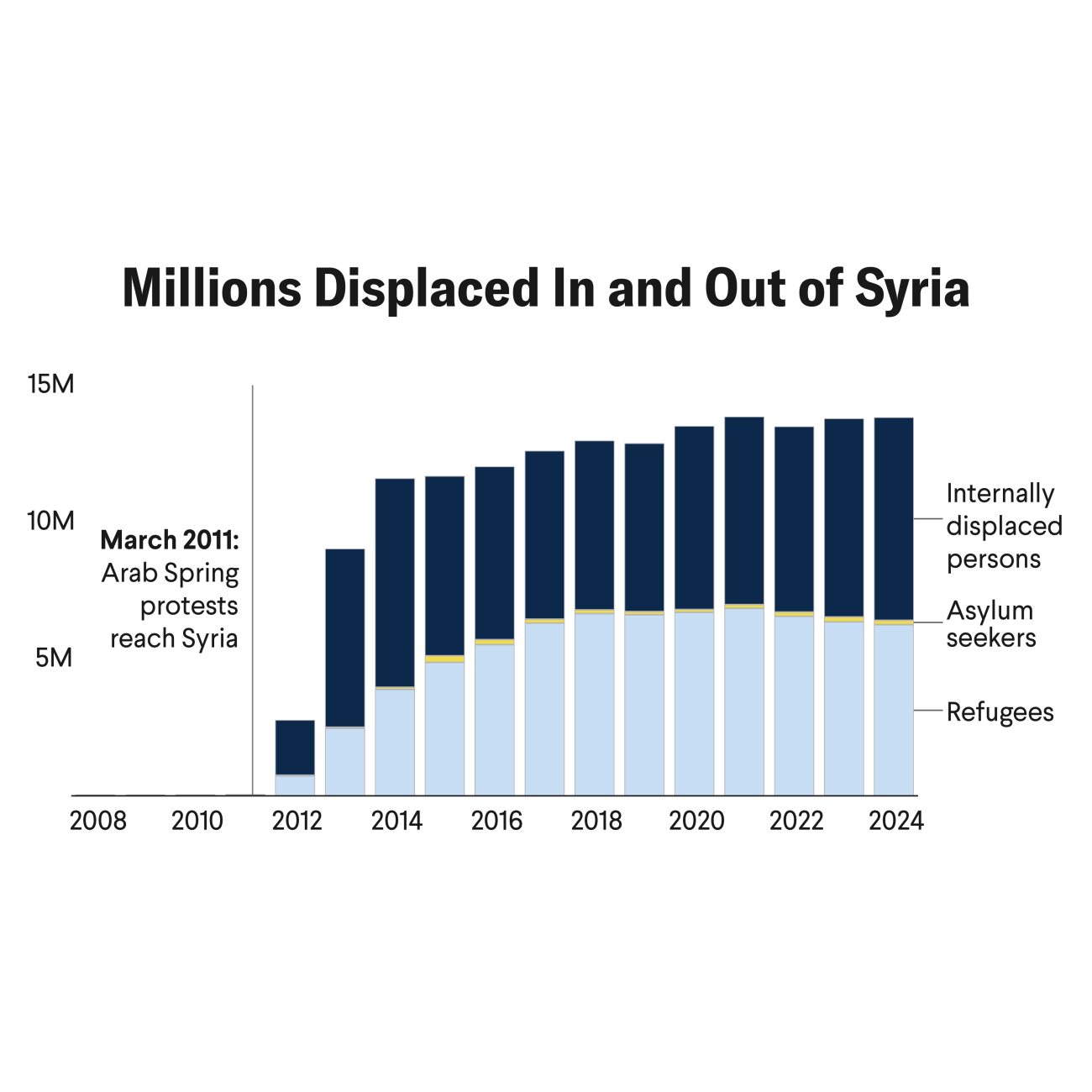

The research raises a question long examined by academics but only recently thrust into the international spotlight by the urgent case of Syria. Eyes are on the Middle Eastern country's decimated health system that it hopes to rebuild as Western superpowers begin to lift sanctions first imposed in response to the crimes against humanity committed by the Bashar al-Assad regime.

The Case of Syria

Syria is evidence of how aid sanctions are rarely applied in isolation. Aid sanctions, financial blockades, trade embargoes, and sweeping secondary sanctions such as the U.S. Caesar Act were intended to punish Assad and protect civilians.

But these measures converged with the devastation of more than a decade of civil war, rampant corruption, and deliberate attacks on health infrastructure and medical workers. The health system is in ruins.

Given no other choice, Syrian doctors personally import medicines and equipment through informal networks, according to an anonymous submission in a 2023 report [PDF] compiled by Alena Douhan, the Special Rapporteur on Unilateral Coercive Measures at the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

Syria has only a handful of functioning linear accelerators for cancer treatment—three in Damascus, one in Hama, and one in Latakia, which is nonoperational.

At Hama National Hospital, according to the Syrian American Medical Society, doctors earn as little as $16 a month. This wage is barely enough to cover transport, forcing many to take second jobs or leave their profession.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are the only lifelines for millions. But, despite formal humanitarian exemptions, such as the UN Security Council's adoption of Resolution 2664, and special licenses for the export of food and medicines, organizations tell Think Global Health that these carve-outs offer little relief against one of their greatest challenges: the "chilling effect."

Overcompliance with sanctions by banks, coupled with de-risking of the private sector who see it safer to cease operations in Syria entirely, have made it almost impossible for NGOs to operate. They struggle to access cash not only to pay suppliers of critical goods, but the salaries of staff who risk their lives to deliver them to people in need.

Two international NGOs interviewed for this story only agreed to speak under the condition of anonymity. One organization in Syria said, "We are not able to facilitate any payments into Syria through official banking channels. The situation is very unclear for many people."

Zuhair Kharat, director of planning at Syria's Ministry of Health, recently told the Sunday Times, "We tried for two months to buy one dialysis machine for Damascus's children's hospital. We had the supplier, the contract, everything. But we couldn't make the payment."

Humanitarian organizations say great risks are being taken with financial transfers, and the sector is increasingly forced to rely on carrying cash as official transfer routes dry up.

Compliance requirements mean a $50 transfer is scrutinized as much as a $1 million one

The same NGO in Syria reported a 48% increase in investigations into their transfers in 2024 over the previous year. In December alone, they faced 93 blocked transactions.

"It's progressively getting worse," said a staff member from this organization, explaining that banks now prioritize risk questions such as "how many high-risk transfers have you made to Syria?" rather than asking how much humanitarian assistance they are facilitating.

"It takes months to resolve delayed payments," the staff member added. "Compliance requirements mean a $50 transfer is scrutinized as much as a $1 million one. We've spent an extra $100,000 a year for the past three years just to manage dialogues with banks to resolve blocked payments."

Unintended Consequences of Sanctions Are Predictable

Researchers said these operational obstructions in Syria are not anomalies, but part of a well-documented pattern leading to direct harm for civilians wherever sweeping financial sanctions are applied.

Although policymakers describe these harms as "unintended," others argue they are anything but. Matteo Pinna Pintor, a researcher commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO) to examine the health effects of economic sanctions in low- and middle-income countries, said this defense is wearing thin.

"Sanctions are not new—there are decades of episodes. Whether consequences are intended or not, they can now be expected," Pintor added.

Pintor's research, alongside a growing body of evidence, shows a predictable pattern: Sanctions can increase mortality, morbidity, undermine nutrition and health-care access, and disproportionately harm the most vulnerable.

A 2022 UNICEF report supports this takeaway, warning that sanctions can have impacts on health comparable to direct armed conflict. It cites research showing that every additional year of sanctions reduces life expectancy by 0.3 years.

Despite these trends, no coordinated mechanism exists to track these consequences in real time, as could be expected for any likely modifier of health in almost a third of the global population.

Pintor and others hoped the research commissioned by the WHO would support the development of such a system [PDF].

But though his findings were met with "widespread interest" from delegates at a regional committee in Egypt two years ago, action stalled. The only other mechanism with the potential to monitor sanctions-related harm is in its infancy, according to its developer OHCHR.

Sanctions Monitoring Faces Political Resistance

Efforts to institutionalize sanctions accountability remains fractured and politically fraught.

The subject of sanctions and their humanitarian impact is undeniably politically sensitive. Special Rapporteur Douhan, a professor who also directs the Peace Research Center at the Belarusian State University, has spent several years attempting to build a monitoring tool to systematically track the humanitarian harms of sanctions. She admits that progress is painfully slow.

"Despite my efforts, even after several years of work to launch the tool and develop a methodology, I'm somewhere in the first stages," Douhan said. Her progress, she adds, has been stymied by resistance from the world's major sanctioning powers.

"It's very problematic to engage in dialogue. Despite my repeated requests, the United States mission has met me only once in Geneva," she said. "When we're talking about the impact on the right to health, they usually do not take the floor. The European Union takes the floor sometimes, but they repeat [that] their sanctions are good, are accepted for the good purposes, and do not have any evidence of humanitarian impact. But, for example, my report about the impact of Unilateral Coercive Measures and the right to health is terrifying."

That report is indeed damning. A finding on thalassemia patients in Iran shows precisely how sanctions and the fear of violating them creates a "chilling effect" as companies are punished for delivering life-saving treatments to civilians. In Iran, thalassemia patients saw their life expectancy plummet from 50 years to fewer than 20 after intensified unilateral sanctions by the United States.

Between 2018 and 2022, deaths among these patients increased sixfold. A Swiss pharmaceutical company that produced thalassemia medicine was fined $17 million by U.S. authorities for delivering them to Iran. Douhan warns that the fear of crossing political red lines is compounding the problem, saying, "I'm afraid that the main negative consequence of unilateral sanctions is a feeling of fear."

That fear is paralyzing action, leaving civilians exposed to harm and ensuring that the impacts of sanctions on health remain invisible, unmeasured, and unaccountable.

Today, that accountability gap has serious implications for countries exposed to abrupt U.S. foreign aid cuts.

The Stanford researchers warn that these sudden aid prohibitions could resemble sanctions in their effects given that no safeguards in place.

"I believe the people who are designing these policies—whether aid sanctions or other restrictions—need information in front of them about what they will do to a country," said Gibson of Stanford.