I am a New York City emergency doctor in a busy hospital at the epicenter of the outbreak. I should be able to be tested for coronavirus. But I am not.

During a strenuous schedule of taking care of COVID-19 patients, I woke up with a headache, fever, and body aches. I knew contracting the disease would be inevitable, but I refused to believe it.

I woke up at 1:00 p.m. to what felt like a brick that had fallen on my head while I was sleeping

After working long hours checking patients' oxygen levels, placing them on ventilators, and treating their fevers in our crowded emergency department, I figured I was just exhausted from overworking. That morning, I canceled all my Zoom meetings and speaking engagements and went back to sleep. I woke up at 1:00 p.m. to what felt like a brick that had fallen on my head while I was sleeping. My husband, who is not a physician, could tell something was wrong because I am not the type to sleep all day. But New York City is no longer the city that never sleeps, and maybe it was me getting acclimated to the current mood of the city.

My temperature read 100.1°F—not quite a fever, but the body aches were unrelenting.

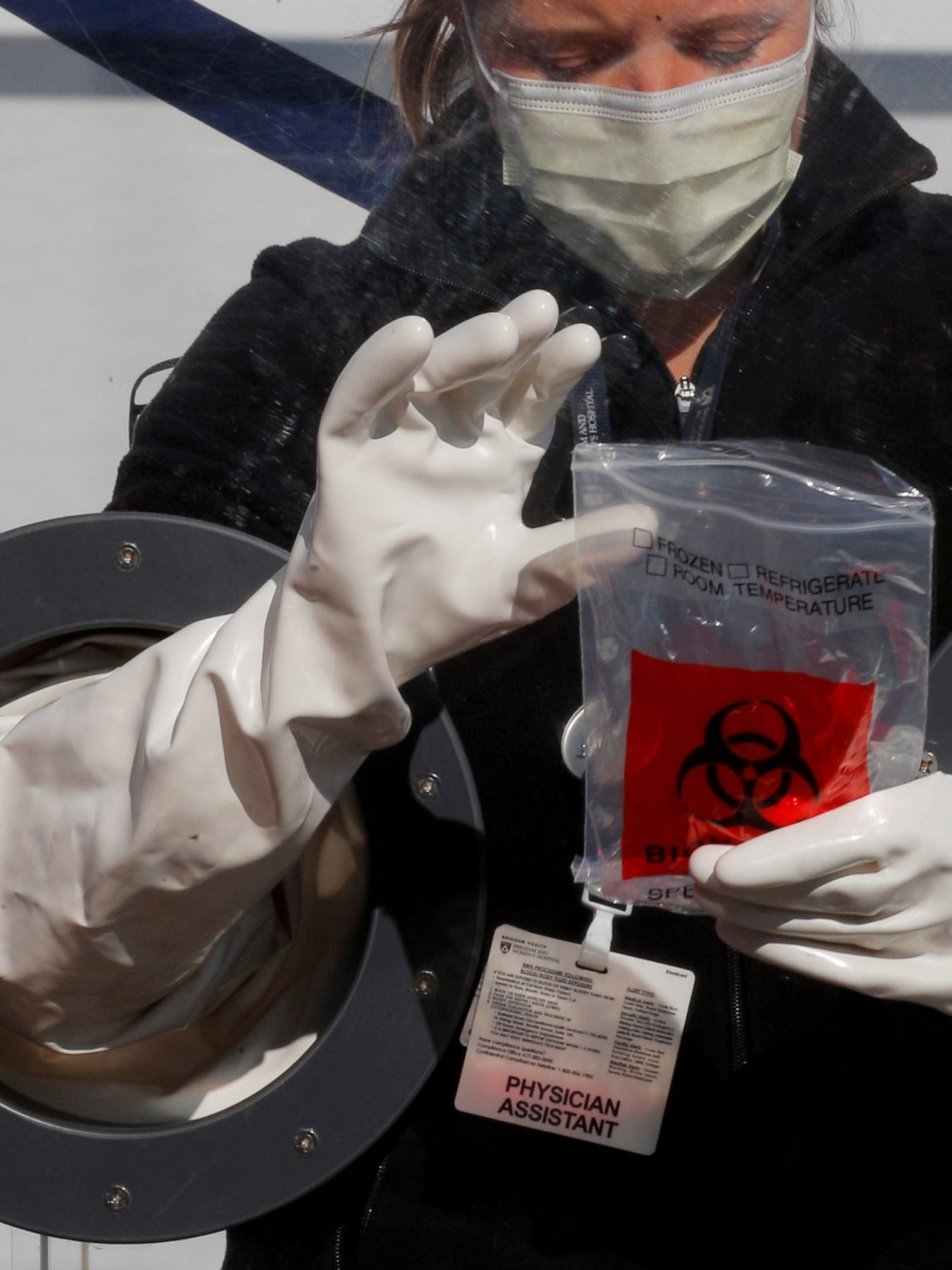

The next day, I took Tylenol and forced myself to eat a bagel. I called my WorkForce Health Safety hotline only to be told that they had stopped offering tests for employees. Then I called the New York Department of Health. After waiting on the phone for more than twenty minutes, they told me they would have to get back to me—but it would be within a week. I called several more hotlines in the city, as well as other hospitals, but most said they had stopped offering these tests for providers altogether.

I called several more hotlines in the city, as well as other hospitals, but most said they had stopped offering these tests for providers altogether

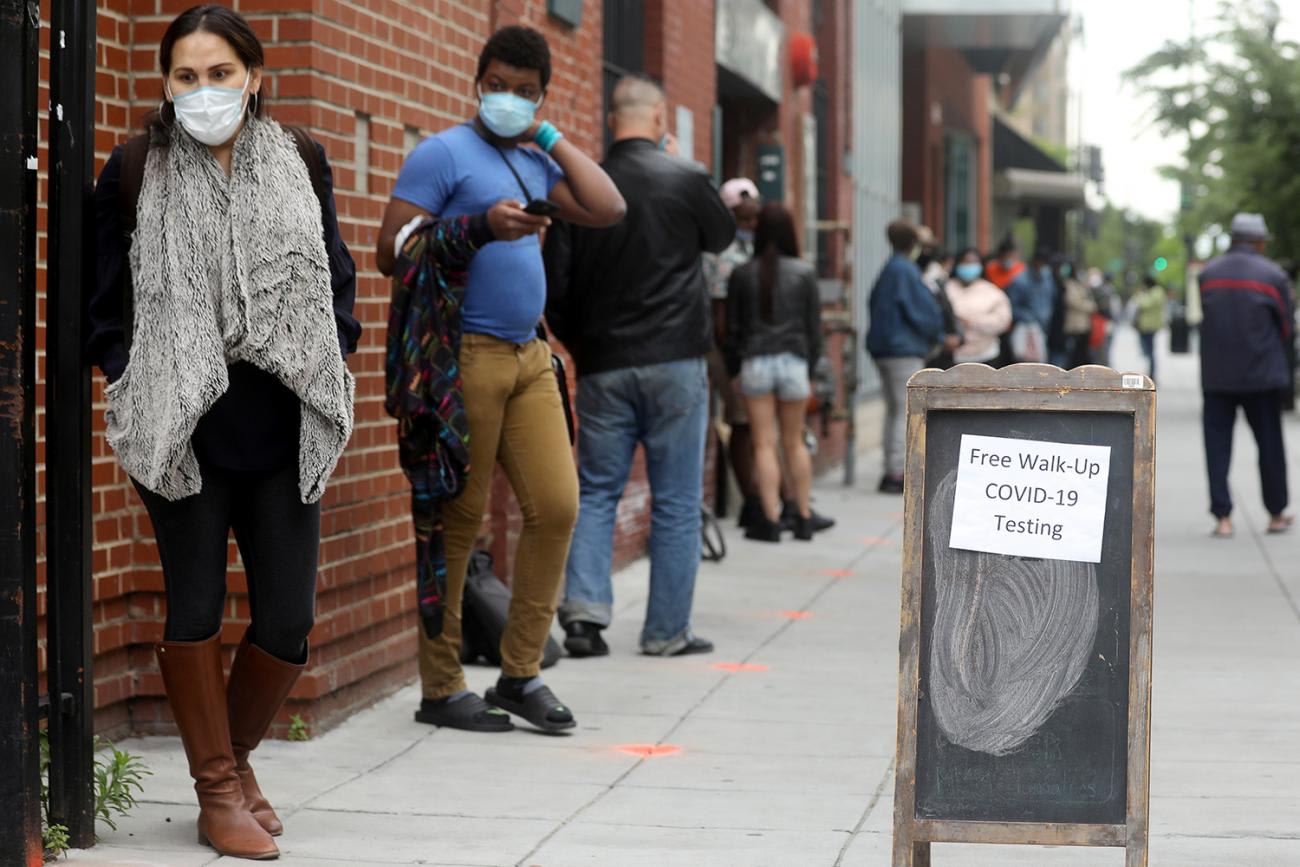

After spending half a workday on the phone, I was left feeling even more exhausted and defeated than ever. I couldn't believe how quickly I had turned from doctor to patient—and what an education it was for me. When I was healthy, I would tell my patients that if they aren't sick enough to require hospitalization, our emergency department will not test them. I gave them the same phone numbers I had attempted to call. Now I was feeling the frustration they must have felt—and worse. Since the New York City area has limited tests, there are strict protocols in place as to who gets access to them, and believe it or not, health-care professionals are not top of the list. Meanwhile, asymptomatic celebrities, zoo animals, politicians, and people in close proximity to the president are getting tested.

Despite all of the symptoms that have kept me in bed for a week, I found enough energy to express my anger on Twitter where I tweeted, "I am a front line health worker in #NYC with symptoms of COVID-19. Health workers are NOT getting tested but asymptomatic people in close proximity to @realDonaldTrump @Mike_Pence are getting tested. #ThisIsAmerica. Please don't tell us we are heroes." After the tweet received 1,800 likes, 825 retweets, and many responses, I realized I was not alone.

"I witnessed and pronounced more deaths in the past week than I have in my entire career—barring the war in Iraq"

I discovered that a few of my colleagues had been tested at the beginning of the outbreak, but now with more and more frontline workers succumbing to this disease, testing health-care workers has become a rarity. This neglect comes despite the fact that over the course of a week, many of us have intubated more patients than we have in the past three years. Personally, I witnessed and pronounced more deaths in the past week than I have in my entire career—barring my service as a medic in Iraq during the war against the Islamic State. I know that testing will not have any immediate change in my clinical outcomes—or at least I hope so—but as a provider who likely acquired this disease due to work-related exposure, getting tested and knowing I will have immunity will give me a much stronger sense of relief and reassurance when I do go back to work. If I don't get tested now, I will have to find ways to navigate the experimental antibody testing.

Toward the end of the week, I tuned in to the president's daily coronavirus task force briefing and listened to President Donald J. Trump go on and on about how America has performed the highest number of tests in the world, followed by several messages about his appreciation for the frontline health-care professionals. The truth is, the United States has done far fewer tests per capita than countries like Germany, South Korea, and Italy. The efficient testing in these countries accounts for their success at containing and mitigating the devastation from this virus.

I may be tired, but my eyes are now wide open

Though it's too late for New York to enact the earlier public health interventions, we can still learn a helpful thing or two from these other countries. First, we need to test all providers, especially the symptomatic ones. Symptomatic providers who would later become immune from this disease will be key players in fighting a future second wave of coronavirus, this time with their personal armor: antibodies. Second, countries like Germany are now preparing for mass antibody testing so people can leave lockdown early. People that recovered from the disease can start going back to work and start building our economy. The United Kingdom is expected to heed the same intervention, too.

I am utterly disillusioned with the systems we have in place in the United States to respond humanely to a crisis like the one in which we find ourselves. I may be tired, but my eyes are now wide open to the gaping holes in our governmental and health-care systems, and I now plead to patients, my colleagues—to anyone who will listen—for us all to work together to do anything we can to stem the loss of life that does not have to occur. We need to learn from other countries and implement their best practices. And most important, we need to adequately test health-care workers so that we will be able to return to work—without us on the frontline, the problems we face will be far graver than we ever imagined.