Until recent decades, investigations of emerging disease outbreaks depended on century-old "shoe leather" epidemiology—public health officials trekking to sites of outbreaks, examining people who were ill, searching for hidden cases, and exchanging information with those at risk of infection. Laboratory diagnostic tests were notoriously slow and often unreliable, depending on the ability to culture pathogens or waiting for suspected cases to develop immune responses—both processes that could take weeks. We have not yet eliminated the need for sending health officials to hot zones for face-to-face meetings with people in affected communities, but the speed of science has changed the laboratory side of the equation. There are now, as never before, opportunities for the international community to work together to investigate an emerging pathogen in real time.

There are now, as never before, opportunities for the international community to work together to investigate an emerging pathogen in real time

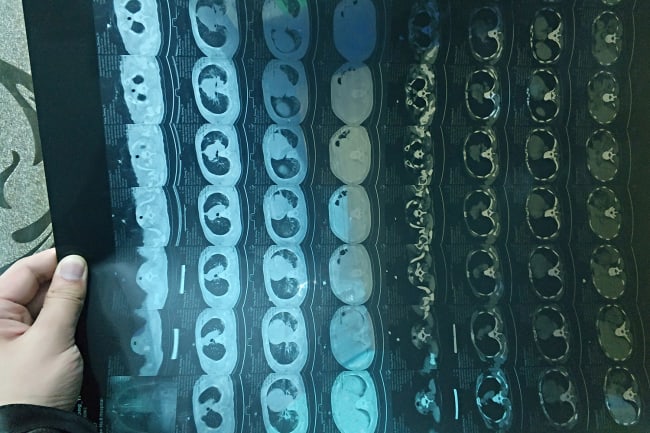

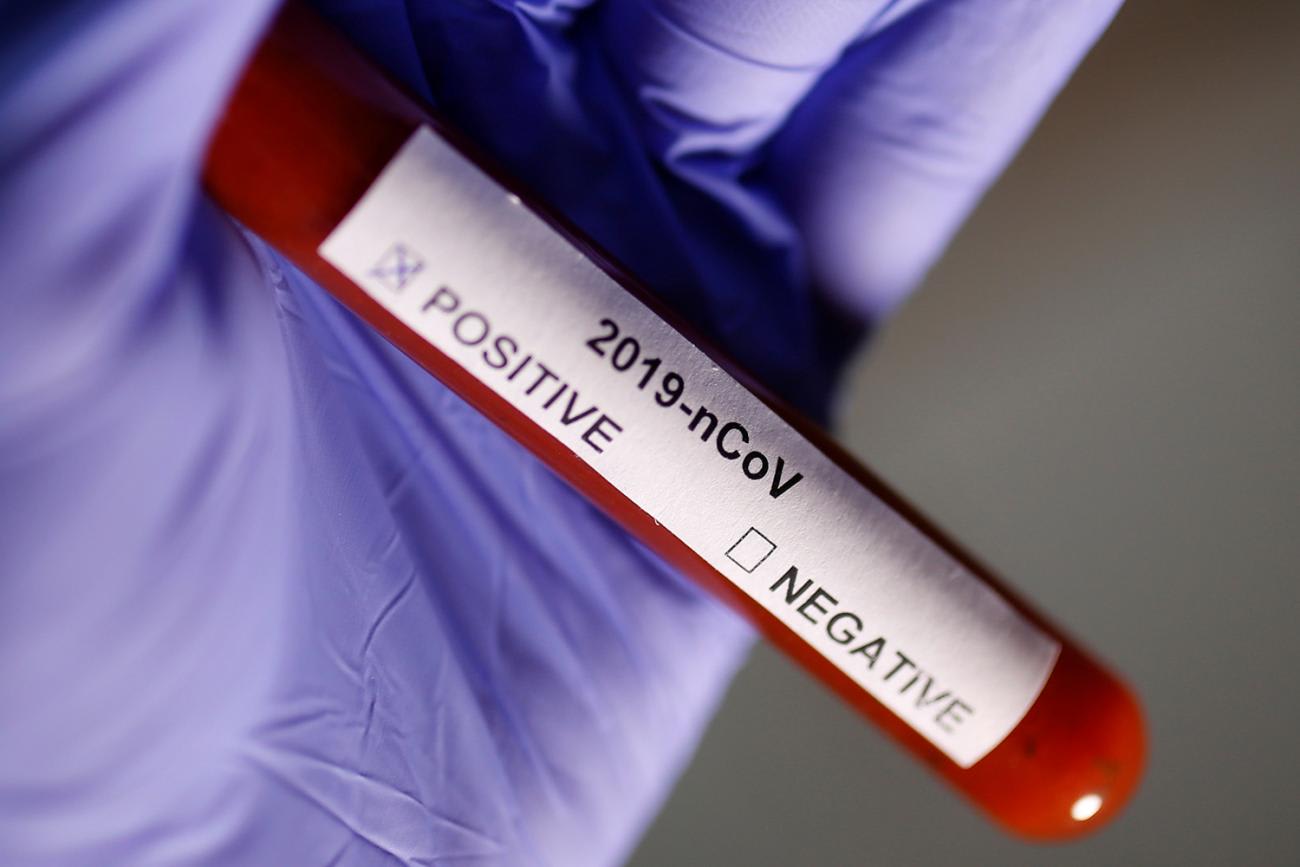

During the first stages of the response to the COVID-19 outbreak, Chinese scientists used real-time PCR, a molecular technique that amplifies very small amounts of nucleic acids for further analysis. This allowed them to identify a coronavirus in samples collected on December 30 from the lungs of a patient with atypical pneumonia. On January 9, the China CDC published preliminary genomic sequence data for the Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus isolate, announcing the causative agent as a novel coronavirus (since named SARS-CoV-2) closely related to a bat strain of SARS-like coronavirus. The sequence was released just three days later. Since then, China and a growing list of countries (including the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Japan, Australia, Finland, Belgium, Sweden, United States, Brazil, and Iran) have published more than 100 full or partial SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences on open-access scientific information platforms like GISAID and Nextstrain.

What does the rapid availability of viral genetic sequences make possible? Genetic sequences help determine the species and serotype (origin of host and location) of the outbreak, identify how long the virus may have been circulating in a population, and predict how the virus is likely to interact with different hosts and respond to available therapeutics. The sequence information can also be used to develop molecular diagnostic tests—and so it did. Immediately upon publication of the novel coronavirus sequences, scientists worldwide began to use the information to design their own primers and probes for real-time PCR assays capable of rapidly detecting SARS-CoV-2 in research and clinical laboratories.

This should be seen as a major breakthrough in our ability to fight emerging infections. Accurate, fast, and reliable testing is critical not only to identifying and treating cases appropriately, but to preventing the further transmission of disease while also understanding community transmission and the role of mild/asymptomatic cases in viral spread. In contrast to the six months it took to develop diagnostic assays for SARS in 2002, diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 were developed and validated in a mere matter of weeks.

U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar II declared COVID-19 a public health emergency on February 4, 2020

On January 23, the laboratory of Christian Drosten at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, along with collaborators from Europe and Hong Kong, published details for a diagnostic test and workflow to detect SARS-CoV-2. The research team verified the test without virus isolates or patient samples by testing specificity against almost 300 patient samples from other respiratory infections. Based on their results, the World Health Organization (WHO) validated and arranged for distribution of test kits to be distributed across member state laboratories, prioritizing the most at-risk countries.

By January 30, WHO director-general declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), a designation that has only been used a half dozen times. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar II declared a public health emergency in the United States on February 4. Both actions are important to mobilizing resources and attention, and as of March 8, nine U.S. states, including California, New York, and Washington, have followed suit with their own emergency declarations.

In the United States, the federal public health emergency declaration authorized the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve new diagnostic tests to detect SARS-CoV-2 under its Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) authorities, temporarily changing the regulatory process to allow FDA to approve the use of unlicensed diagnostics, given the urgency of the situation. Like other national reference laboratories, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) used the published sequences from China to develop a new diagnostic test in-house. In early February, CDC used its International Reagent Resource network to distribute COVID-19 testing kits to partners, including the network of state public health laboratories that are vital to detection and tracking of infectious disease outbreaks.

U.S. diagnostic capabilities have been limited to the CDC laboratory in Atlanta and a handful of additional laboratories

Issues with the kit's performance caused CDC to limit the number of state laboratories authorized to perform the test—and, ironically, the Emergency Use Authorization authority constrained the freedom of state public health laboratories to develop and validate their own in-house diagnostic tests. While South Korea and other countries beyond China have tested tens of thousands of suspected COVID-19 cases since February, U.S. diagnostic capabilities have been limited to the CDC laboratory in Atlanta and a handful of additional laboratories. A number of factors led to issues with the diagnostic lag in the U.S. ranging from manufacturing to bureaucratic and economic constraints. Initial issues arose when the five states designated to receive test kits found inconsistencies validating one of the three test components. CDC had to pull all testing in-house while creating a two-component test for state distribution, taking both time and resources.

With a new approval process outlined for laboratories certified to perform high-complexity testing and further FDA guidance on emergency use authorization, commercial laboratories are stepping up with their own diagnostic tests, which should be available soon. However much these delays are now a thing of the past, their significance may be felt for weeks to come. They limited early access to diagnostic testing for COVID-19 in the United States.

In the coming weeks, reported U.S. cases are likely to dramatically increase as improved CDC reagents and FDA policies expand the number of laboratories equipped to test suspected COVID-19 cases. There may be difficulties in reporting whether these indicate a major shift in community-level transmission, or better information—with implications for public trust and confidence in U.S. public health authorities at home and abroad.

The COVID-19 outbreak has, so far, demonstrated two developments in the role of technologies and laboratory diagnostics in the international response to emerging disease outbreaks. First, the COVID-19 pandemic represents the first time scientists informed outbreak preparedness and response by sharing and using genomic sequence data shared in almost real-time through open-source platforms, rather than waiting for live virus isolation and characterization.

The extent to which the U.S. response to COVID-19 was hampered due to limited access to reliable diagnostic testing remains to be seen

To be fair, data alone is not enough. While laboratories can conduct research and develop diagnostics based on the viral genome sequence data published on open-source platforms, they still require virus samples to validate their methods, develop serological tests, and test vaccine candidates. The WHO has emphasized the importance of sample sharing in public statements. While a framework exists for the sharing of influenza samples, the same rules do not necessarily apply to sharing of other novel pathogens of public health concern, which highlights the need to revisit those rules and develop a broader framework for sharing samples. Nonetheless, the rapid sharing of data by government scientists, using methods and platforms available to experts worldwide, has accelerated the speed of the international response to COVID-19.

The extent to which the U.S. response to COVID-19 was hampered due to limited access to reliable diagnostic testing remains to be seen. Support to public health laboratories at all times, during routine public health activities and in response to epidemics, is critical to confirm cases and understand transmission dynamics. The United States has a backbone of state and local health laboratories capable of viral diagnostic testing—but that's only possible when they have access to reliable and accurate diagnostic tests. Laboratory systems are critical to our capabilities to detect, confirm, and respond effectively to emerging disease outbreaks, and they are rarely appreciated until something goes wrong. Now is the time to appreciate them. They may yet help to contain COVID-19, and there is work to be done to make sure valuable time isn't lost in a future epidemic.