On March 28, devastating earthquakes shook central Myanmar. With a mainshock of 7.7 magnitude and aftershocks up to 6.7, this event is the most significant earthquake series to strike in Myanmar since 1912.

The earthquake leveled several towns and villages, killing more than 3,500 and injuring 5,000 as of this writing. Another 210 remain missing. At least three hospitals have reportedly collapsed, including one in Mandalay that fell "like waffle sheets crumbling" under the strain of the tremors. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared that health workers in the affected areas have been overwhelmed by the number of patients requiring urgent medical attention.

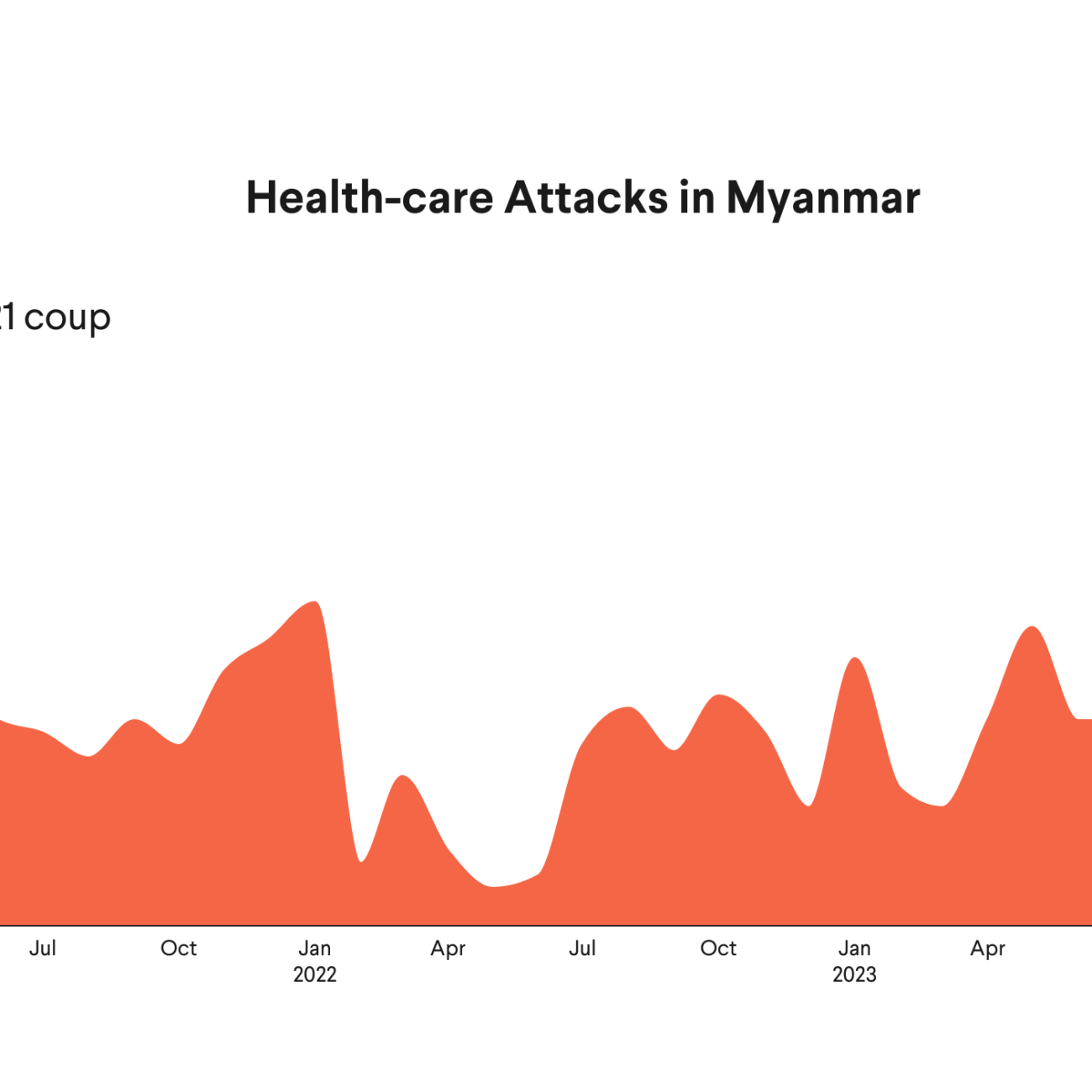

The natural disaster places even more strain on Myanmar's health system, which has been under attack and systematically targeted by the country's ruling military junta since a coup in February 2021. The junta has continued its attacks following the earthquake, the BBC reporting that airstrikes took place on communities in the hours immediately following the devastation, bombing those trying to rescue survivors from the rubble. The military junta also has a record of blocking aid from reaching areas where it is needed most, a pattern being repeated now.

The conflict, in its fifth year, created one of the world's worst yet most overlooked humanitarian crises prior to the earthquake. Health workers continue to face daily targeted attacks as they seek to provide care to the sick and wounded. Recent foreign aid cuts by the United Kingdom and United States also imperil critical aid programs in Myanmar.

Disease and Displacement in Myanmar Since the 2021 Coup

Myanmar had been making progress toward a sustained period of peace and democracy until the 2021 coup reignited conflict. The human cost of this conflict is enormous: The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported before the earthquake that approximately one-third of Myanmar's population, approximately 18.6 million people, required urgent humanitarian assistance, and more than 3 million were displaced into remote, underdeveloped border areas.

Mass displacement forced people from cities and towns into small villages and internally displaced persons camps in rural areas, driving a rise in infectious diseases. Drug-resistant malaria has surged by 1000% in some regions, driven in part by forced migration moving people into rainforest regions with higher malaria incidence and making treatment more difficult to access. Similarly, multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis has skyrocketed since 2021, taking Myanmar's incidence rate to more than four times the global average.

Essential medicines and equipment are consistently blocked from ethnic regions and border areas where displaced populations seek refuge. These military blockades have directly contributed to the spread of preventable diseases, leaving children particularly vulnerable in the face of plummeting vaccination rates. A resurgence in once-controlled diseases such as polio, measles, and diphtheria is now a threat, endangering Myanmar's people, neighboring countries, and global health efforts.

In an article published on Think Global Health in March 2024, Myanmar's health system was described as a battleground. Since then, the crisis has deepened, with more than 1,500 total attacks on health-care workers and infrastructure, and according to the nonprofit organization Insecurity Insight at least 135 health-care workers killed since 2021. Health workers anticipate constant, relentless possible attacks on themselves, patients, and hospitals.

Drug-resistant malaria has surged by 1000% in some regions following the 2021 coup

The military junta has tried to prevent health-care delivery. Attacks using artillery and explosives have been common, including explosives dropped on health facilities from junta fighter jets. Armed drones also pose a growing threat, allowing the junta to cause devastation on the ground from a remote location.

Despite the attacks, Myanmar's health workers operating outside military-controlled areas remain resilient, providing care in a parallel health system by adapting to new challenges against the odds, including cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and foreign aid from various European countries, including the United Kingdom. Since the earthquake, Myanmar's latest challenge, health workers are providing free care on the streets of Mandalay.

Health Workers in Myanmar

The UK Health Partnerships for Myanmar, coordinated by Global Health Partnerships (GHP) and funded through the UK Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget, has provided support to the country's health workers since 2014. This collaboration includes health professionals and their Medical Royal Colleges and provides medical education, guidance, and support to Myanmar's health workers. Over the past four years, the organization has conducted nearly 200,000 telemedicine consultations, supported online medical education for up to 1,000 junior doctors, and offered certified online degree courses for nurses.

The future of programs such as the UK Health Partnerships for Myanmar is now uncertain, following the announcement by Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer that the UK ODA budget would be reduced to 0.3% of gross national income (GNI) by 2027 to fund an increase in defense spending. In her spring statement, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves revealed further detail about the UK government's plans to reduce ODA against the timeline the prime minister set out. Three-quarters of the cuts will be delivered before 2027, with £0.5 billion ($636 million) expected in 2025–26, followed by huge cuts of £4.5 billion ($5.7 billion) in 2026–27, and the final sum of £6.5 billion ($8.3 billion) to be cut in 2027–28, when UK ODA will reach 0.3% of GNI.

The cuts to USAID announced by President Donald Trump in January 2025 are also certain to inflict damage on Myanmar. Recent analysis by the Centre for Global Development shows that these cuts are worth a total of $14,284,000 in Myanmar, including ending all funding for the agency's Diversity and Inclusion Scholarship Program (DISP). The sudden end to this program, which supported students from marginalized groups—including those from ethnic minorities and with disabilities—to access higher education will likely further exacerbate health workforce shortages in Myanmar and place even further strain on the country's battered health system. On April 5, U.S. aid workers responding to the earthquake were also laid off.

These cuts are not only morally repugnant but also shortsighted, according to former USAID officials. Prior to the current political unrest and countrywide armed resistance against the military, Myanmar was already classified as having a critical shortage of health workforce, having only 17.8 health workers per 10,000 population [PDF] before 2021. This situation will have only been worsened during the current conflict, leaving the country not even reaching half the WHO's threshold health workforce requirement of 44.5 health workers per 10,000 [PDF]. Now, with health workforce training and education already disrupted, cutting programs such as DISP will only exacerbate the existing health workforce shortages.

Those currently providing health care in Myanmar are also likely to leave the workforce to escape the brutality of the military council, either while the conflict is ongoing or soon after it ends. During a December 2024 visit to the Thailand-Myanmar border, GHP representatives spoke with health workers providing care along the border and in mobile medical teams. One health worker from Kayin State told us they are seeing a sharp rise in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the health workforce, which they only expect to rise further given that many of those providing care to the sick and wounded while under attack from the military are currently living their trauma and have not yet reached posttrauma.

The critical shortage of health-care workers in Myanmar, paired with the targeted attacks on health infrastructure and the changing global funding environment, paints a particularly bleak picture for the future of health care in the country.

In the immediate term, following the tragedy of the March 28 earthquake, aid agencies sending support to the country must ensure that it reaches those most in need.

In the words of UN Special Rapporteur Tom Andrews, "[The junta] weaponize[s] this aid. They send it to areas they have control of, and they deny it to areas that they do not. . . . that has been the pattern of their response to natural disasters in the past. I'm afraid I'm fully expecting that will be the case with this disaster."

The global community should unite to protect the delivery of health care in Myanmar and, critically, to safeguard health workers from systematic attacks. Rather than cutting aid programs, donors with the means to help should continue investing in universal health coverage, supporting frontline health-care workers including through direct aid, to respond to Myanmar's escalating multiple health crises.