In the six weeks since M23 rebels in Democratic Republic of Congo staged a violent takeover of Goma, a major humanitarian and minerals trading hub in the eastern part of the country, horrific bouts of violence and a sprawling humanitarian crisis have unfolded across the region. The conflict has spawned mass displacement, cuts to water and electricity, and direct attacks on health-care operations.

"When the military left . . ., they opened the weapons stock. Everybody could help themselves," said Gang Karume, a Congolese researcher and technical advisor living in Bukavu, the eastern region's second largest city, which was captured by rebels soon after Goma. He was staying near a military barrack when the fighting hit. "They just started shooting in the air, shooting in disorder. I'm telling you—it was really bad. It was brutal."

As violence continues, humanitarian aid workers must grapple with new hurdles: the sudden U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), the U.S. retreat from foreign aid, and the widespread termination of humanitarian assistance programs run by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

Despite a waiver that purported to continue assistance for lifesaving aid, organizations have received little funding to continue operations, according to a memo from former USAID official Nicholas Enrich. Among the terminated programs was a project in DRC providing the only source of water to about 250,000 displaced Congolese living in camps near Goma.

"Someone who relied on aid for more than a decade—they wake up in the morning and [hear] 'you're no longer getting HIV medicine because it's finished. You no longer have potable water,'" said Karume. "[These are] the consequences for the poorest of the poor."

"We had one experience . . . in a hospital right in Goma, when bullets pierced the roof of the operating theater during a [surgical] procedure," said Will Cragin, a humanitarian policy advisor at Doctors Without Borders. In early March, the United Nations reported that 130 patients suspected to be part of opposing forces were snatched from their hospital beds and taken to undisclosed locations.

The Making of Eastern DRC's Humanitarian Crisis

The recent surge in violence is the latest in a decade-long conflict, which experts now fear could escalate into a wider regional war. Players include neighboring Rwanda, which backs the M23 rebel group, as well as Burundi and South Africa, which also have troops in the country, and Uganda.

Driven by a struggle for valuable land and minerals, deep-seated ethnic tensions, and political hostilities, the conflict in eastern DRC has led to more than 6 million deaths since 1996. According to the Congolese government, the current violence has added another 7,000 deaths since January and displaced 400,000 people.

"There are safer ways to access Congolese minerals than killing its people," said Karume. He stressed that drivers of the conflict were both external and internal, adding "Corruption is really killing the country. Nepotism is killing the country."

The resulting instability has made access to essential services—including basic health care, nutrition, and sanitation—a challenge, contributing to excess deaths from knock-on factors such as disease spread and starvation.

When violence comes, deaths from other causes come with it

Les Roberts, professor emeritus

"When violence comes, deaths from other causes come with it," said Les Roberts, a professor emeritus at Columbia University who spent nearly three years working in eastern DRC. "When we look at our mortality surveys, children and pregnant women are the ones most likely to experience these excess deaths."

In addition to having a maternal mortality rate more than double the global average in 2020, the country has battled a multitude of infectious diseases. Most recently, it has been the center of a growing mpox outbreak as well as a mystery disease that has killed at least 60 people and sickened more than 1,000.

Worsening matters, nearly 25% of the country's population face food insecurity, and 4.5 million children are acutely malnourished. A previous "mystery illness" detected at the end of last year was later revealed to be a combination of severe malnutrition, malaria, and COVID-19.

The existing health and humanitarian crisis has deteriorated on all fronts, leaving hospitals overwhelmed and aid workers scrambling to meet the growing need. Sexual violence is a major concern: The United Nations recorded at least 60 cases of rape per day during the last two weeks of February.

As well as directly threatening safety, the violence has driven mass displacement, complicating existing public health efforts and increasing the risk of wider disease outbreaks. Mpox clade 1b, a deadlier strain of the virus already present in 24 countries, including the United States, risks spreading further within DRC and beyond its borders.

"In Goma, we had more than 187 mpox cases in treatment centers. When the fighting started there, they had to flee," said Boureima Hama Sambo, PhD, MPH, the WHO country representative for DRC. "When [there is no] isolation site to treat those who have a disease, . . . contact tracing going to be an issue. And it can multiply contacts, because people [flee to] communities."

The United States Turns Its Back on Goma

Caught in the crossfire, many low-income and marginalized communities in DRC relied on foreign aid activities for basic care, food, and medicine. The United States was the country's largest contributor—providing the largest overall share of foreign aid last year—more than $1 billion in humanitarian and bilateral assistance per year.

"Humanitarian action [in DRC] was funded by close to three-quarters—more than 70%—by U.S. funds [in 2024]," said Hama Sambo. "You can imagine the extent of the gap left behind by the suspension of U.S. funding and withdrawal of the U.S. from the WHO."

Those directly involved with USAID's operations in DRC, including aid workers, stressed how valuable foreign-funded health programs were to communities that needed them, at little cost to the United States.

"It's not perfect, but a lot of these vaccination activities, malaria treatment—are pretty darn cost-effective," said Roberts. "In most of the USAID-funded projects I worked on in eastern Congo, for less than every $300 spent, a child didn't die—we would never tolerate these cuts if Americans understood how common my experience is."

In March, the United States officially terminated 83% of USAID contracts. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in a statement that the programs "did not serve (and in some cases even harmed)" U.S. interests.

"Today, aid is being more and more inexorably linked to political agendas. It's legitimate to say, 'I need to understand how the money is being used.'" said Karume. "But if we are in a partnership, you don't [suddenly] say 'I'm gone.' . . . We don't accept the lack of respect for African partners."

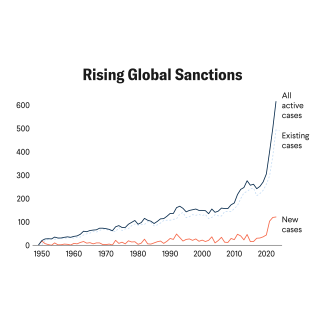

For those in DRC, only a commitment to end the fighting will improve the humanitarian crisis. Experts emphasize that sustained international pressure—particularly on Rwanda—is key. Although Canada, European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States imposed sanctions on Rwandan officials in recent weeks, the slowness of the international response could have emboldened M23 rebels and allowed the humanitarian crisis to deepen.

The United States can also no longer withhold foreign aid, once a key source of diplomatic leverage, to exert additional pressure. Instead, the Donald Trump administration is exploring a deal with the Congolese government to provide access to minerals in exchange for security assistance, equipment, and training to DRC's armed forces, echoing a similar negotiation in Ukraine.

Some onlookers theorize that the U.S. retreat from the global stage could have motivated the rebels' decision to advance on Goma on January 26. "There's widespread perception in eastern DRC," Roberts added, "that our failing to have diplomatic skills triggered the timing of this."

Given the conflict's political and economic dimensions, as well as its steep human cost, advocates agree that DRC's ongoing violence demands much more global attention than it has received.

"The international community . . . needs to advocate for peace. [Only] through [peace] is the end of the long suffering of the people in this region," said Sambo.