The coronavirus pandemic continues to unfold as the swells begin to subside from Hurricane Hanna, whose landfall was centered not far from Houston where we both attended university. We are left with little appetite for taking a fresh, cleansing breath. The global count of COVID-19 infections exceeds 10 million, and our nation's shortcomings are becoming increasingly clear.

We are left with little appetite for taking a fresh, cleansing breath

There are more than 50,000 new coronavirus cases per day in the United States. To honor the lives lost and the sacrifices of those on the frontlines, we must learn from this crisis and meet tomorrow's challenges at the scale required. We must buttress the shaky foundations of the systems that have made the jobs of health-care heroes so difficult and address the factors driving disparity. Through dramatically reimagining our health care and public health infrastructure, we can keep health systems from becoming overwhelmed, promote community health, and protect individuals from illness in the first place. We can achieve this through expanding health capacity, improving access to prevention and intervention, and addressing the social determinants of health.

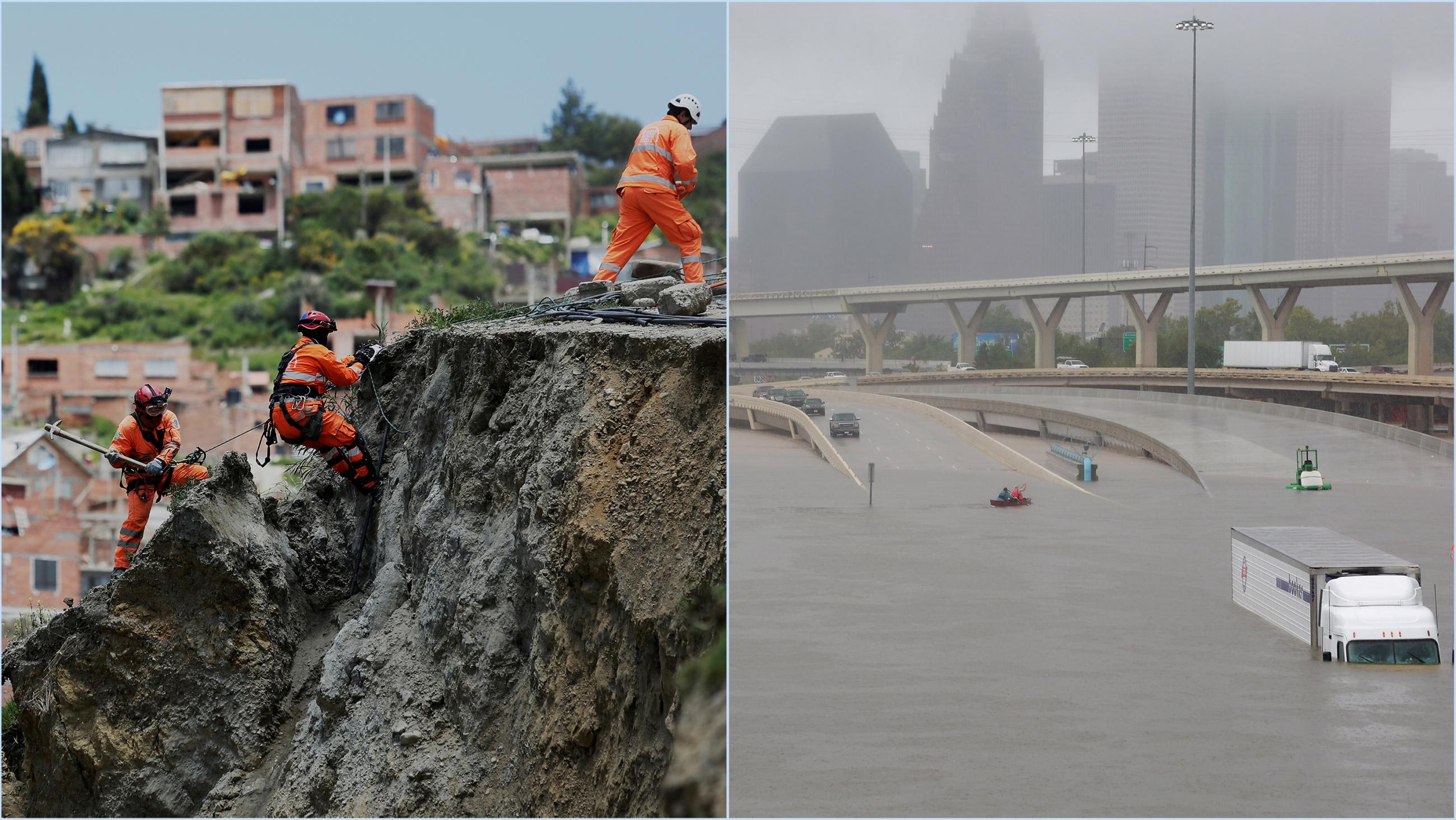

To prepare for the challenges ahead, we must first increase hospital capacity with awareness of our changing world. Driven by these factors and by the growing climate crisis, we will face more pandemics, hurricanes, landslides, and other disasters. Vector-borne pathogens are likely to become more prevalent and spread more rapidly as well.

We watched our city reel as it struggled to address food and drug shortages, staffing problems, and overrun health care and social services

During our undergraduate days in Houston, we confronted one of these disasters, Hurricane Harvey. Making landfall in August 2017, Harvey caused catastrophic flooding, resulting in the death of dozens and the destruction of homes and businesses, resulting in over $100 billion in damages. We watched our city reel as it struggled to address food and drug shortages, staffing problems, and overrun health care and social services. Two other historic hurricanes followed weeks later, pushing the already-strained local, regional, and national disaster response capacity to the brink. Hurricane Maria leveled Puerto Rico, taking nearly a year to get electricity back to its residents. Hurricane Irma hit Southern Florida as the most powerful Atlantic ocean hurricane in recorded history. As much as we prepare for future storms, what if events like these happened at the same time in the same place?

As we've seen in Michigan where, earlier in the COVID-19 crisis historic rainfall led to the failure of a dam and severe flooding, this possibility is very real in many places. Be it Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines during COVID-19 or the ongoing cholera outbreak and flooding in Somalia in recent years, we ask ourselves whether our hospitals are prepared to face natural disasters and a global pandemic concurrently?

Are hospitals are prepared to face natural disasters and a global pandemic concurrently?

How would local governments in other hot parts of the United States or the world prepare to provide cooling centers to protect against heat-related deaths in a time that calls for social distancing? Hand-washing protects against COVID-19, but how would a state encourage citizens to abide by these guidelines amid a historic water shortage as faced by South Africans just two years ago? We should take COVID-19 as a costly warning. Moving forward, we must expand national stockpiles of ventilators and other crucial supplies, invest in expanded bed capacity, and better support local health departments to meet the needs of their communities. Our disaster preparedness plans must be driven by evidence and science, both of which point to a future that will force us to prepare for worst-case scenarios and then consider that these multiple disasters for which we prepare might just happen together.

Prevention and Coverage

Expanding capacity is insufficient. We must also address illness before it strikes and provide affordable, accessible care when it does. In the United States, health insurance coverage gaps challenge effective prevention and disease management.

Better positioned to both manage chronic needs and confront crises

Our health-care systems should be universally accessible and proactive, not reactive and restrictive. Worldwide, we've seen how countries with health-care systems rooted in collective and communal values are better positioned to both manage chronic needs and confront crises. For poor people in Canada, their chances of receiving better health care is 36 percent greater than those of their American counterparts. COVID-19 has exacerbated coverage challenges as the economic effects of COVID-19 drive unemployment to unprecedented highs, stripping employment-based insurance from more Americans, particularly low wage earners.

While the uninsured and underinsured have always weighed the financial consequences of seeking care, COVID-19 has highlighted the public health and societal costs of settling for a system that has pushed so many to forgo testing, treatment, and life-saving intervention over concerns over the cost of said care.

Those hospitalized with COVID-19 could pay as much as $74,310 if uninsured or out-of-network

One uninsured woman was charged nearly nearly $35,000 for a COVID-19 test and related outpatient emergency room visits. Lawmakers have since made coronavirus tests free (with certain stipulations), but those hospitalized with COVID-19 could still pay as much as $74,310 if uninsured or out-of-network. These examples are not isolated to the current crisis; more than half of Americans avoid needed needed medical care due to costs. If we hope to defeat COVID and future health challenges, Americans must seek testing and care when they need it to protect their personal health and community health. In this sense, our inability to achieve universal health care is not only a moral absurdity but a public health liability.

Social Determinants of Health and the Built Environment

As we expand health-care capacity and access to care, we must also mitigate the environmental exposures, built environment, and other factors that predict health outcomes and drive disparities. Health disparities observed during COVID-19 illustrate how disasters impact different communities in profoundly different ways.

The conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, can point us to the root causes of these disparities

Social determinants of health, the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, can point us to the root causes of these disparities. Better preparation for the disasters of tomorrow depends on addressing social determinants of health today. Access to clean air is one of these determinants that drives health. Champions of environmental justice have long sounded the alarm to pollution's detrimental health impacts. From increased health-care costs to lost worker productivity and increased rates of school absenteeism, our inability to secure clean air for all communities has a real cost. A foundational study published in 1979 found that air pollution in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania cost residents $9.8 million in annual hospitalization costs. These trends have not changed, and this disparity for environmental justice communities is not unique to the United States. The cost of air pollution to the United Kingdom's National Health Services and social care will be 6.52 billion in U.S. dollars from 2017–2025.

It's also important to recognize the links between people's living environments and their health. Recognition of the inseparable ties between health conditions and the built environment is nothing new. Researchers have long found that access to green space in one's neighborhood improves mental health, physical health, and social cohesion.

In New York City during the pandemic, the authorities acknowledged this relationship by closing some streets to car traffic entirely to encourage socially distant exercise. However, many communities have limited access to these spaces. To create healthier communities moving forward, we must create environments that promote good health with a deep appreciation for addressing longstanding disparities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, overwhelmed infrastructure, challenges to access to care, and disparities in health outcomes have underscored the need for change. Community resilience requires the expansion of public health infrastructure and health-care systems, insurance coverage, and access to care. Moreover, these changes should be implemented with the awareness of how where we are born, live, and work affects health.

One person cannot stop a pandemic from infecting a population, and one neighborhood cannot protect itself from a hurricane, but if we acknowledge the realities of tomorrow with a shared commitment to one another, our nation can weather any combination of storms.