The Donald J. Trump administration has implemented sweeping changes to U.S. immigration policies during the coronavirus pandemic that are contributing to the global burden of COVID-19. One such change is a CDC order that limits immigration by barring individuals "from countries where an outbreak of a communicable disease exists" from entering. As a result of this order more than 41,000 individuals who arrived at the U.S.–Mexico border since March have been expelled without the opportunity to seek asylum. However, the United States itself has the highest number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the world. As we move forward in this crisis, the United States must both control the outbreak within its own borders and examine how its policies are affecting other countries.

More than 41,000 people who arrived at the U.S.–Mexico border since March have been expelled with no asylum opportunity

U.S. immigration policies are actively worsening the domestic public health crisis, as well as exacerbating it within other countries. Undocumented immigrants have a higher risk of contracting COVID-19, a problem further compounded by the lack of health care and financial resources. Additionally, when they are placed in detention centers run by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), they are often exposed to conditions that promote the spread of disease. Finally, these same people are often deported without appropriate testing, aggravating outbreaks and damaging U.S. diplomatic relations.

Undocumented Immigrants are at Increased Risk for COVID-19

Undocumented immigrants are more susceptible to COVID-19 due to inadequate protection against the virus and lack of access to care. The largest number of immigrants come from Mexico, and studies suggest that Hispanic and Latinx individuals are disproportionately vulnerable to COVID-19 in at least some communities. Most undocumented immigrants work in low-paying jobs in agriculture, manufacturing, and custodial services, which have largely been deemed as essential fields. These working environments often increase their risk of exposure and make it difficult to maintain social distancing.

These working environments often increase their risk of exposure and make it difficult to maintain social distancing

Moreover, the pandemic response has largely overlooked their financial needs. Currently, the spouses of undocumented immigrants are not eligible for stimulus checks. The proposed American Citizen Coronavirus Relief Act would expand existing eligibility requirements to allow mixed households to qualify. However, given remaining financial burdens, many immigrants choose to remain in jobs despite facing significant risk of infection. Food, housing, and financial insecurity have been shown to worsen the mental and physical health of undocumented immigrants. Moreover, undocumented immigrants have limited access to health insurance due to eligibility restrictions and lack of employer coverage. Lower levels of health literacy, due to language barriers and complex policy requirements, also decrease their likelihood of seeking medical care or lead them to visit overburdened community health centers and clinics instead of hospitals.

The Public Charge rule, which was published by the Department of Homeland Security last year, is an emblematic example of a policy requirement that impedes access to care. Under the rule, the government can deny a visa due to an individual's use of government programs, such as cash assistance from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services updated this rule to encourage all symptomatic individuals, 'including undocumented individuals,' to seek necessary treatment and/or preventive services. However, many are unsure about which federal services they qualify for and still fear the loss of their pathway to citizenship.

More than eleven million undocumented immigrants are integrated into our communities. By providing targeted support for this population and protecting them from COVID-19, we safeguard both their health and that of the entire public.

Detention Centers Have Inadequate COVID-19 Protections

In addition to facing increased risk within community settings, more than 20,000 immigrants are currently held in Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers that lack appropriate public health protections. Although the agency has published a set of Pandemic Response Requirements, many facilities fail to adhere to these guidelines in practice. Individuals held in detention centers report that they receive limited health information from staff, hygiene and cleaning products are often unavailable, and there is no comprehensive screening for high-risk individuals. Some are even forced to buy soap from commissaries to wash their hands. Other facilities have provided caustic disinfectant supplies that cause burns, bleeding, and eye damage.

More than 20,000 immigrants are currently held in ICE detention centers that lack appropriate public health protections

Given the crowded and unsanitary conditions inside facilities, thousands of public health and medical experts have pleaded with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to release additional detainees. However, because of limited voluntary release, many must petition courts for release, as in a recent ruling that mandated that children be released from family detention centers. Although there have been substantial decreases in detainee numbers, many high-risk individuals remain in detention. As of late June, there have been more than 2,700 confirmed COVID-19 cases and at least three related deaths in detention centers. Given the reports of conditions inside facilities, existing measures appear to be insufficient to contain the spread of the disease.

Comprehensive testing is key to ensuring that asymptomatic cases are identified and isolated before individuals infect others. However, as of June 4th, more than 50 percent of those tested were positive and only a small number of facilities enacted widespread testing. Additionally, continuing transfers and new admissions to detention facilities drastically increase the potential for new transmission.

Continuing transfers and new admissions to detention facilities drastically increase the potential for new transmission

The projected consequences of COVID-19 outbreaks within detention centers are alarming. In other settings of incarceration, such as San Quentin prison, more than 1,000 of the 3,700 total prisoners became infected within mere days of its first reported infection. Additionally, models estimate that 72–100 percent of detainees in Immigration and Customs Enforcement facilities may become infected within ninety days and quickly overwhelm community intensive care capacity. Given these foreboding reports, many immigrants are at high risk of contracting COVID-19 within detention centers, which may have profound ramifications on the abilities of community hospitals to treat others.

Deportations Increase Disease Burden Abroad

U.S. immigration policies are not only inhibiting domestic efforts to fight the pandemic, but are also worsening conditions in other countries. The practice of deporting those who are likely infected or who haven't been tested has provoked conflict with governments in Latin America and the Caribbean and burdened their already struggling health-care systems.

By mid-April, more than 75 percent of Guatemalan deportees had COVID-19—almost a fifth of the country's confirmed cases

The most prominent relationship harmed thus far has been that with the government of Guatemala. In Guatemala, dozens of deportees have tested positive. Of all deportees by mid-April, more than 75 percent tested positive for COVID-19, amounting to almost a fifth of the country's confirmed cases. The Guatemalan government repeatedly requested that the United States test deportees, requests that the Department of Homeland Security refused to fulfill. When Guatemala threatened to stop accepting deportation flights in response, President Trump issued an executive order threatening to impose visa sanctions on Guatemalan citizens and government officials. Eventually, the Department of Homeland Security agreed to certify that deportees to Guatemala have tested negative before removal. Despite this, dozens of deportees have still tested COVID-19 positive upon arrival. The U.S. response demonstrates an individualist approach to a global pandemic, damaging our diplomatic relations and potentially exacerbating the total disease burden.

Guatemala is not alone. The Mexican government has made similar requests for testing. But the Department of Homeland Security has refused to grant these requests even as Mexico continues to receive hundreds of deportees daily, some of whom are visibly sick and thought to be responsible for a recent outbreak at a migrant shelter. Haiti, one of the most vulnerable countries in the region, has also received COVID-19 positive deportees, and unsuccessfully appealed to the United States to halt flights. Jamaica and Colombia have made similar requests.

ICE carried out an average of seventy-five deportation flights per week between March and mid-June

The practice of deporting detainees with coronavirus is damaging relations with many governments, a situation likely to worsen as the United States struggles to contain its domestic infections. Beyond this, it endangers the deportees themselves. They not only face potential exposure to infections on flights, but shelters that would normally receive them on arrival are closing out of fear. In April, several communities in Guatemala attempted to burn down a government building where deportees were being quarantined. Despite this, Immigration and Customs Enforcement continues to deport thousands of individuals, carrying out an average of seventy-five flights per week between March and mid-June.

Policy Solutions

Current migration policies toward undocumented immigrants are creating a destructive ripple effect from local communities to the rest of the world that exacerbates the burden of COVID-19. Immigrants, largely undocumented, who staff low-wage and essential jobs are at higher risk for contracting the disease. This vulnerability is intensified by instability in their living situations and lack of access to care. Deployment of public health workers at community health centers and clinics could support undocumented individuals in navigating public services. Finally, since many immigrants are fearful of seeking medical care, additional legislation is necessary to protect medical settings from Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers.

Immigrants, largely undocumented, who staff low-wage and essential jobs are at higher risk for contracting the disease

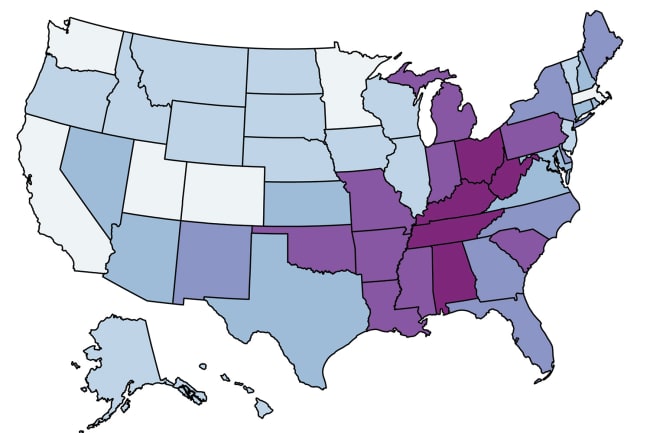

Moreover, work sites such as farms, factories, and grocery stores must be held to strict, clear, and consistent safety guidelines that ensure the safety of undocumented immigrants on the job. The Occupational Health and Safety Organization (OSHA) should issue enforceable site requirements and conduct on-site evaluations to protect workers. If the agency continues to refuse to set an emergency standard for COVID-19 workplace conditions, states should be supported in implementing their own regulations, such as those proposed in Virginia. Once undocumented immigrants are detained, critical changes must be made to ensure their health and safety. Increased transparency about testing and positive cases is needed. While Immigration and Customs Enforcement has slowed arrests to reduce density in detention centers, the agency itself recognizes that the projected target of 75 percent capacity is insufficient to allow for adequate social distancing. They should take far stronger measures to reduce density among detainees. Furthermore, detainees should be comprehensively tested, especially before transfers between facilities.

Testing is also pivotal before deportations. While the testing of Guatemalan deportees is commendable, continued positive cases suggest that the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency conduct more thorough testing and quarantining. If properly applied to deportees to all countries, not just Guatemala, these measures could blunt the detrimental effects that deportations have on recipient healthcare systems and end the damage being done to U.S. relationships throughout the Americas.

As COVID-19 infections continue to rise, it is critical to reexamine U.S. immigration policies that are impeding effective responses to the pandemic. Several measures can be taken to reduce the risk that undocumented immigrants' vulnerability, as well as poor detention and deportation practices, pose to public health.