As a psychology scholar, an advocate for immigrant rights, and a formerly undocumented Venezuelan American, I know firsthand that anti-immigrant politics are harmful to human health.

Research has indexed the degree to which immigration policies at both federal and state levels in the United States have historically embraced structural racism and xenophobia. This research examining a decade of policies contributes to a larger body of studies revealing that the United States has an anti-immigrant policy climate. This comes as no surprise to anyone who follows the political narrative around immigration, particularly during elections.

Over the past two decades, the anti-immigrant approach to policy and politics has gone national, taking center stage during election cycles. Anti-immigrant legislation has multiplied, again at both federal and state levels, and the health of immigrants has suffered significantly. Again, the country is in the middle of a presidential election and the health and well-being of immigrants is at stake. Immigration continues to be a defining issue, drawing sharp contrasts between the candidates, between hate and humanity.

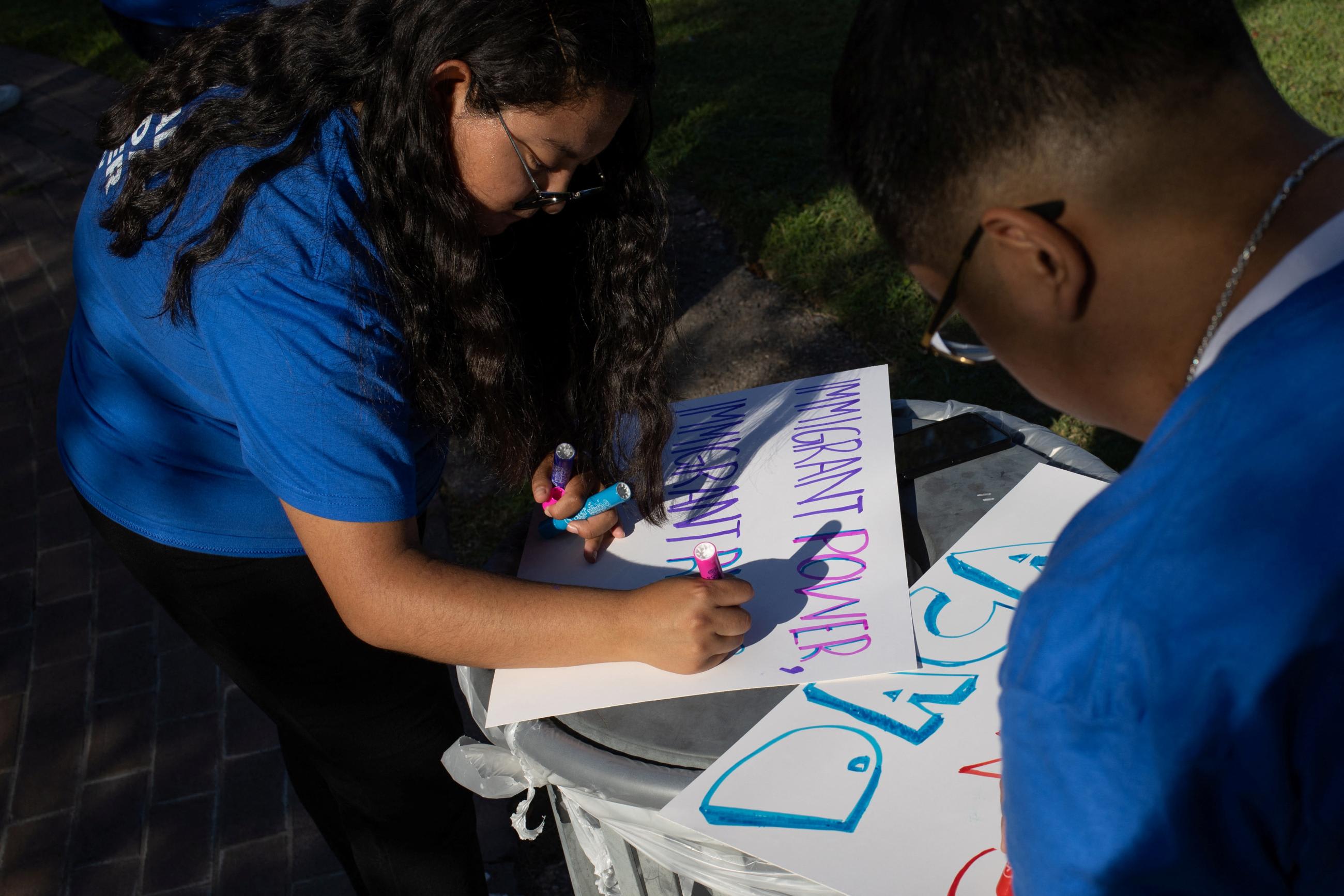

This election cycle, immigrants are protecting their mental health through action. Over the past 10 years, my academic career has been dedicated to understanding how immigrants' involvement in social change is linked to healthy outcomes, and to using these insights to inform interventions and programs to support them.

Several studies demonstrate that experiences with discrimination are associated with lower outcomes in mental health, education, and physical health. Research also shows a link between lacking access to a protected immigration status—being undocumented or having a temporary status—and high levels of psychological distress and discrimination. However, my research shows that becoming involved in advocacy and activism is a powerful tool for immigrants to protect their well-being in the face of hostility.

Research shows a link between lacking access to a protected immigration status and high levels of psychological distress and discrimination

Living in Arizona as a young person without legal immigration status in the 2000s made me a target of anti-immigrant hate. Coming of age amid a flurry of local anti-immigrant laws meant that I was not allowed to do what most young adults can, such as get a driver's license, buy health insurance, receive care without concern over being asked by health-care providers about my immigration status, access higher education with financial support, travel across borders, or enjoy a life without fear.

In 2010, local politicians radicalized their anti-immigrant speech to get elected, weaponizing xenophobia and racism among voters. This built on years of intentional criminalization of immigrants by the state's sheriff, who grew in popularity using these tactics. They passed extreme bills, such as the "show me your papers" legislation, intended to give local law enforcement the power to racially profile individuals and inquire about their immigration documents. This climate affected my well-being, exacerbating a sense of anxiety over my future and my family's. This effect is in line with a growing body of literature drawing a link between policy and immigrant health.

However, my experiences in Arizona helped me develop psychosocial strengths, allowing me to respond to anti-immigrant hostility and protect my mental health in the process. l became critically conscious about inequity and injustice, becoming motivated to step out of the shadows with other students and activists at the time. I marched, protested, and lobbied for immigration policies to be reformed. I took big risks, such as sharing my story publicly, hoping to humanize our plea. I joined a larger movement that pushed for national policies such as the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, known as the DREAM Act.

At the local level, I both helped create programs such as Dreamzone to better support undocumented students in higher education and advocated for better state policies. I was fortunate to have found a sense of belonging, purpose, and empowerment during some of my darkest moments as an immigrant. This is why I remain hopeful that our immigrant community will survive these elections and will emerge stronger.

Several of my studies and other researchers' have shown that experiencing discrimination and exclusion are motivators for critical consciousness, such as reflecting on inequalities and taking actionable steps to address them. These actions may include advocating for oneself within institutions and systems as well as joining community groups and organizations to advocate for structural changes in policy.

The research in this area, including my own, demonstrates that a greater sense of critical consciousness is linked to a greater sense of political agency to create social change, improved mental health, positive health behaviors, stronger academic performance, greater college persistence, and higher career aspirations.

In a recent study to be published in the American Journal of Community Psychology, we report on a collaboration with colleagues from the Latinx Immigrant Health Alliance and United We Dream, the largest youth-led immigrant activist organization in the country. We developed and tested a framework that explains how immigrants' engagement in electoral activism, anti-racism, and immigrant rights are associated with several coping mechanisms.

Adding to this sense of hope, our studies have found that critical consciousness and political agency can be promoted through educational programs within institutions—including schools, community colleges, universities, health-care training settings—and that mental health outcomes are largely positive for immigrant communities and their providers.

Immigrants' engagement in electoral activism, anti-racism, and immigrant rights are associated with several coping mechanisms

Clearly, research tells us that making an effort to overcome injustice is how we survive. The actions we take on social justice and health matter because they put us on a path toward becoming more psychosocially empowered. This is how our immigrant communities become stronger.

I go back to my Arizona days to understand these findings in my own context. Almost 15 years after the passage of the "show me your papers" bill, the young activists with whom I mobilized voters have formed organizations and programs that embrace the cultural diversity of the state and have become leaders in education, health care, and other sectors, shaping policy and leveraging their political power to prevent further harms toward our community.

One example is Aliento, an immigrant-led organization that provides healing workshops and educational programs to promote the well-being of immigrant youth and that supports the empowerment of these youth to advocate for more welcoming policies in the state.

Anyone, whether from the United States or abroad, can lend their skills and energy to support local immigrant groups. A group of psychology leaders and immigrant activists from across the country recently designed a model with recommendations for community-based advocacy, designed to help people engage in collaborative advocacy within their communities.

Everyone can support immigrants in protecting our health against the toxicity of hate and help move the United States and the globe toward a path of healing.