Over the past six months, more than two billion doses of vaccines against COVID-19 have been administered worldwide. As more doses go into people’s arms, countries with early access to vaccines have begun exploring how to safely “return to normal.” Many nations, particularly those looking to reopen their borders to international travelers, see a solution in “vaccine passports”—vaccination certificates, either paper or electronic, that verify a holder’s vaccination status and can be used to exempt vaccinated individuals from pandemic-related restrictions.

The use of vaccination certificates in this way can be pro-public health, incentivizing individuals to get vaccinated and reducing the risk of a gradual reopening. However, such success depends on equitable access to vaccines and clear, global standards. Without international consensus or widely available vaccines, these “vaccine passports” can neither incentivize the reduction in vaccine have-nots nor reduce the risk to them and those whose immunity may be at risk. Instead, they may actually serve to further cement the divide between vaccine haves and have-nots. Unfortunately, that danger is fast becoming a reality with COVID-19. High-income, dose-rich countries have taken a nationalized approach to COVID-19 vaccine certification, threatening to leave behind the billions without widespread vaccine access.

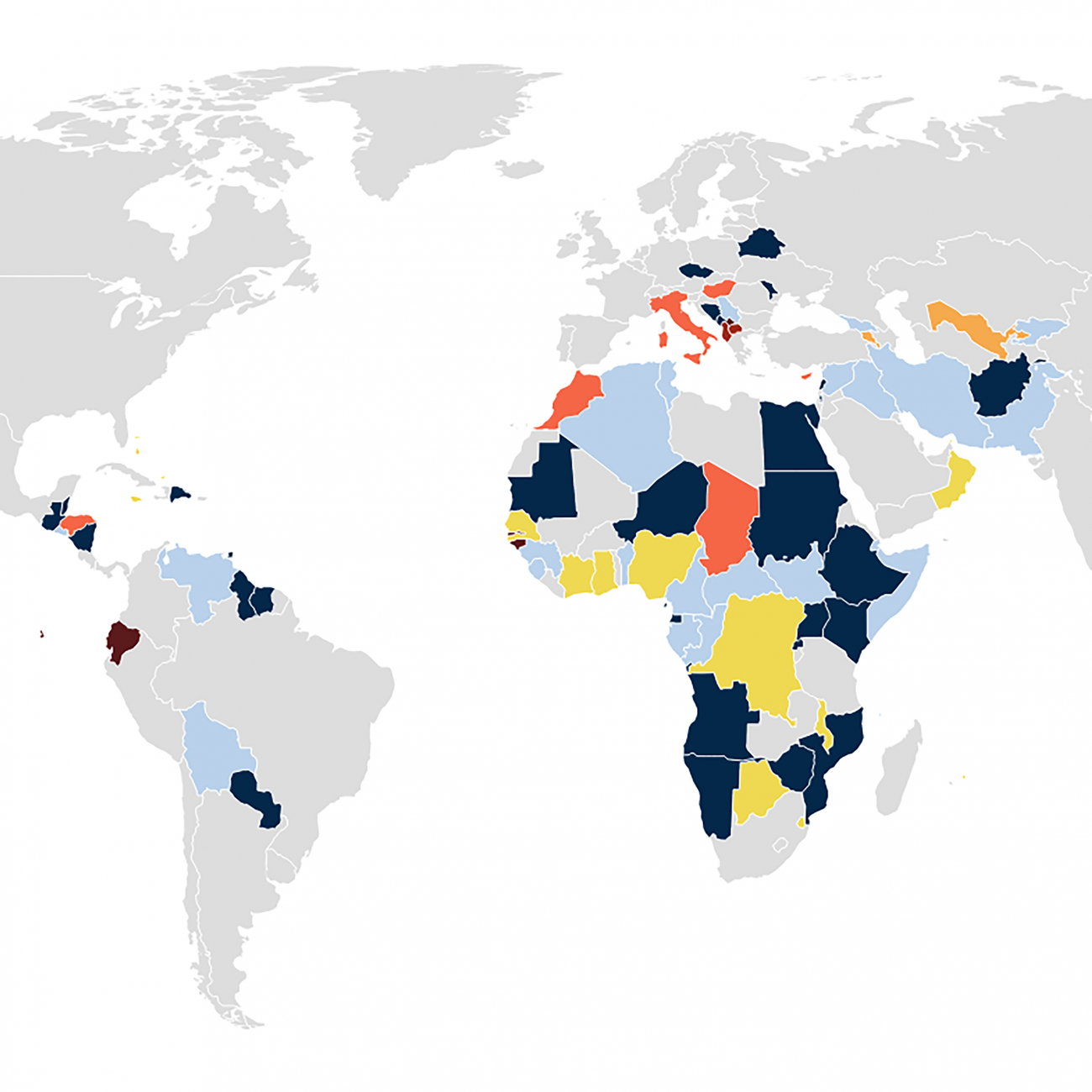

Based on government websites, official statements, and media reports Think Global Health has identified 88 countries, as of June 3, using or considering vaccine certificates for international travel. Twenty-four nations are also using or considering vaccine certificates to exempt individuals from domestic restrictions, such as limits on gatherings, indoor activities, and internal movement. A full database with sources is included below. This tracker will be updated regularly.

Under the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR), requiring or even recommending proof of vaccination against specific diseases for travel is permissible. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) currently allows for countries to require travelers to provide proof of vaccination against yellow fever for entry. However, such measures must be non-discriminatory, health-based, and no more restrictive than other reasonable alternatives. Given the unknowns regarding vaccines’ efficacy in reducing transmission of the novel coronavirus and concerns over inequitable global vaccine access, WHO has recommended against requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccination as a condition for international travel. That recommendation has not stopped countries, however, from embracing COVID-19 vaccination certification at and within their borders, often in a haphazard and nationalistic way.

So far, a universally accepted private sector or UN-led system of vaccination certification has not taken hold. Though increasingly popular among airlines, the travel passes created by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and CommonPass are accepted by just a handful of countries. Additionally, the WHO Smart Vaccination Working Group has been focused on security standards, rather than creating an accessible certification tool.

Instead, countries and regional blocs have taken a go-it-alone approach. Israel famously rolled out the Green Pass, an application that verifies the vaccination status of users, granting the vaccinated access to restaurants, gyms, and other indoor activities and a few quarantine-free travel corridors. The European Union is implementing the Digital COVID-19 Certificate, a pass designed to exempt vaccinated individuals from restrictions such as testing requirements or quarantine when traveling between EU member states. Similarly, the Gulf states are considering a regional pass, while most East and Southeast Asian countries are using or working on national applications and systems. A few countries, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean, are not using dedicated systems to verify records and are simply requiring presentation of vaccination certificates issued by national authorities.

Just as the methods for certification vary widely from country to country, so too do the benefits of vaccination. Travelers with a valid vaccine certificate can enter Guatemala, for instance, without the need for quarantine or a negative test, but in Mongolia, proof of vaccination only allows travelers to quarantine at a home or hotel, rather than in a centralized quarantine facility. In Denmark, the government is allowing vaccinated citizens to access some non-essential businesses with proof of vaccination, while Australia’s proposed system would restrict movement between Australian states. In the United States, the Biden administration has declined to pursue a federal vaccination certification system, leaving some states like Hawaii and New York to roll out their own standards for vaccine certification, while nearly twenty states have outright banned “vaccine passports.”

This fragmented approach, particularly on the international side, may seem confusing given the widely-held assumption that tourism and global interconnectedness would force uniform standards for vaccination certification. However, six months into global vaccine rollout, tourism is not driving use of vaccination certificates for international travel. Instead, the use of vaccine certification does not differ significantly between tourism-dependent and tourism-independent economies.

Even among nations using vaccination certifications for international travel, most countries are not allowing all vaccinated travelers to enter. Instead, nations in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia are only granting quarantine-free or testing-free travel to vaccinated travelers from particular countries, almost all of which have similar levels of rates vaccination and national income. In other words, a fully vaccinated traveler from South Africa will not enjoy the same freedoms and privileges as a fully vaccinated traveler from France.

While this lack of global consensus on vaccine certification poses challenges to all nations, the burden falls particularly heavy on low- and middle-income countries. High-income countries represent 61 percent of all those using or considering vaccine certification for international travel and 75 percent of those using them domestically. Conversely, only two low-income countries, Tajikistan and Uganda, are using vaccine certificates for international travelers, and not a single low-income country is using them domestically.

Only two low-income countries, Tajikistan and Uganda, are using vaccine certificates for international travelers

While income is, of course, not the sole determinant for whether a country is using or considering vaccine certification, income has played a significant role in vaccine access, which matters for vaccination certification. The countries using vaccine certification for domestic or international purposes are not just more likely to be high-income countries, but they are also more likely to be those with the highest rates of national vaccination. On average, countries using vaccination certification for travel are administering more than five times the number of doses per 100,000 of population than those not using them.

Early in the pandemic, wealthy countries purchased much of the world’s early vaccine supply, leaving low- and middle-income countries now dependent upon donations or the multinational COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access program COVAX for access. While wealthy nations expect to vaccine 70 percent of their population or more by summertime, vaccine supplies will remain insufficient for the billions living in poorer nations well into 2022. Vaccine certifications, as they are currently being used, threaten to deepen the economic consequences of that global vaccine inequity.

Vaccination certification could be a powerful tool to reopen the world in a safe and equitable way. So far, however, vaccine passports are only reopening the world for the wealthy few.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors would like to thank Thomas J. Bollyky and Jennifer Nuzzo for their assistance.

This tracker was first published on June 3, 2021.