Five months into the largest vaccination campaign in world history, global rollout has been marked by deep inequity. Just nine countries are responsible for three-quarters of the more than two billion doses administered worldwide.

One way to bridge this gap between the vaccine-haves and vaccine-have-nots would be for countries with early access to doses to donate some of their supplies to other nations without sufficient access, particularly those struggling with surging cases. Think Global Health is tracking to what extent such transfers have occurred.

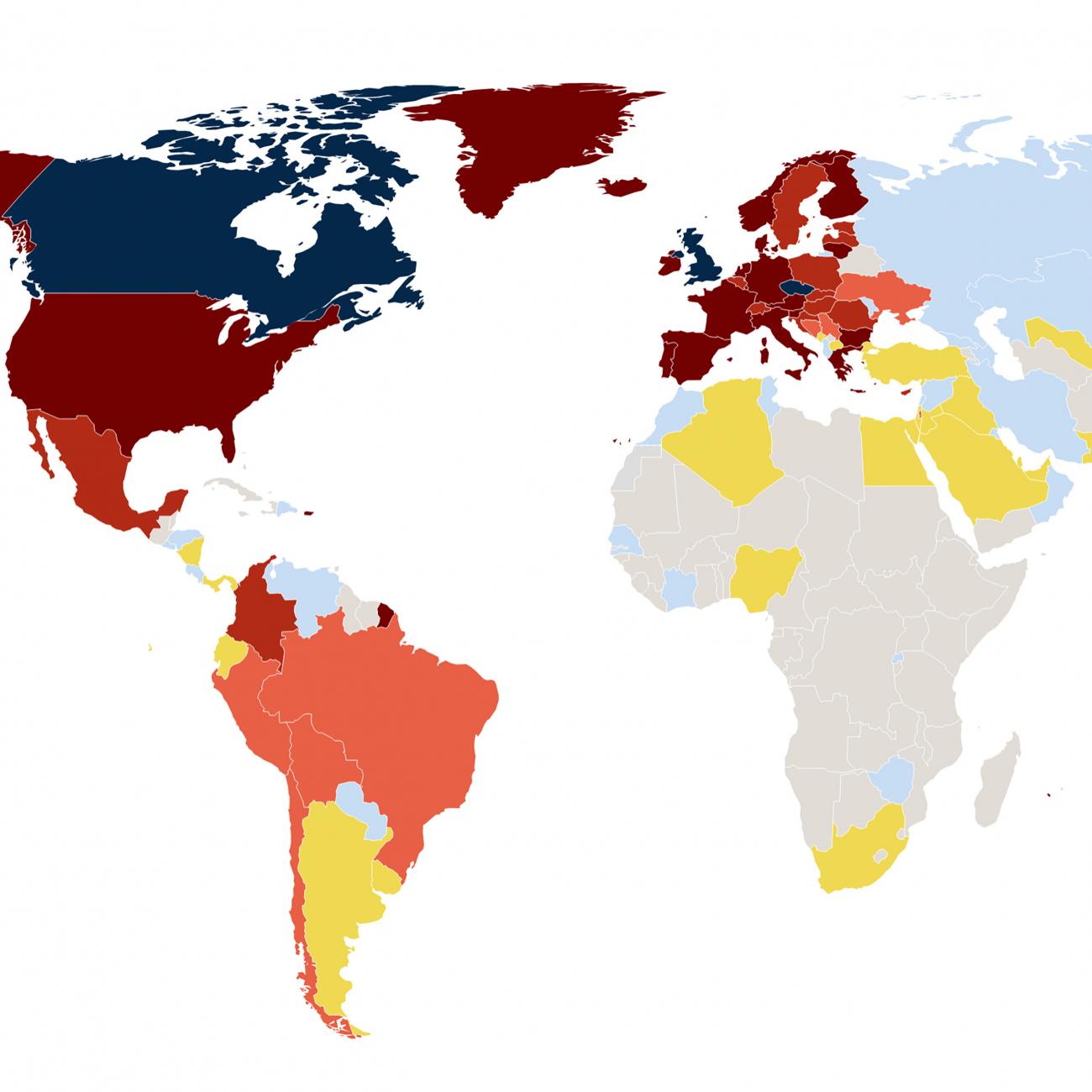

Based on government websites, official statements, and media reports, as of June 4, Think Global Health has identified 28 countries that have donated a total of 46.4 million doses to 120 nations. The first half of this article will explore the nature of these donations, and the second will explain how vaccine diplomacy—the use or delivery of vaccines to advance political goals—is motivating four vaccine donors: China, India, Israel, and Russia.

A full database with sources is included below. This tracker will be updated regularly.

The Donors

Most donations are still proceeding bilaterally, but more governments are committing to donate some of their surplus vaccines through the multilateral initiative known as the COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access program, or COVAX. The timeline for most of these donations remains unclear, and only two countries, France and New Zealand, have reallocated any doses through COVAX to date. Moreover, though donors have committed doses to certain regions or countries, some worry they are sacrificing influence over recipients by working through COVAX rather than bilaterally.

As such, most vaccine donors are opting to bypass COVAX and instead directly provide doses to recipient nations.

The Donations

To date, most bilateral vaccine donations have been small—200,000 doses or fewer—and because all gifted vaccines require a two-dose regimen, the average donation is enough to fully protect just 100,000 people. But averages do not capture the disparities between donations. With few exceptions, donor countries have not distributed vaccines according to the population size or the severity of the coronavirus crisis in recipient nations. While the multilateral initiative COVAX, is allocating vaccines in amounts proportionate to the population size of the recipient nation, vaccine donors are not. Many small nations, particularly in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean, have received enough doses to vaccinate more than 10 percent of their population; in contrast, more populous recipient countries have received enough to fully protect no more than 1 percent of their populations.

Nor are countries receiving vaccines in proportion to their current burden of COVID-19. While the true number of infections is undoubtedly much higher than recorded in many nations, especially in regions and countries where testing rates are low, the majority of recipient countries are getting donations in excess of their recent case numbers. For example, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Afghanistan all received donations ranging from 1.2 to 2.2 million doses despite reporting relatively few COVID-19 cases. India, the hardest-hit country in the South Asia region, has yet to receive any vaccines, although that will change when the United States begins sharing its AstraZeneca supply.

When looking at regional allocation of vaccine doses, distribution is even more inequitable. Countries in East and South Asia have received 55.59 percent of all pledged donations, despite having just 20.73 percent of confirmed cases since November 2020. In contrast, Latin America and Eastern Europe, which continue to suffer high case burdens and have struggled to secure vaccine access outside of COVAX, are receiving far fewer donated doses than necessary to keep pace with their current outbreaks. Argentina, Colombia, and South Africa, for instance, have accounted for 4.83 percent of all global cases since November, but administered just 1.22 percent of all vaccine doses. None have received a single donation.

If donors are not distributing COVID-19 vaccines on the basis of need or equity, what is driving donations? China, India, Israel, and Russia, the four countries that have taken a global approach to vaccine diplomacy—i.e., providing vaccines to at least ten countries on three continents or more—have largely done so in alignment with their national and strategic interests.

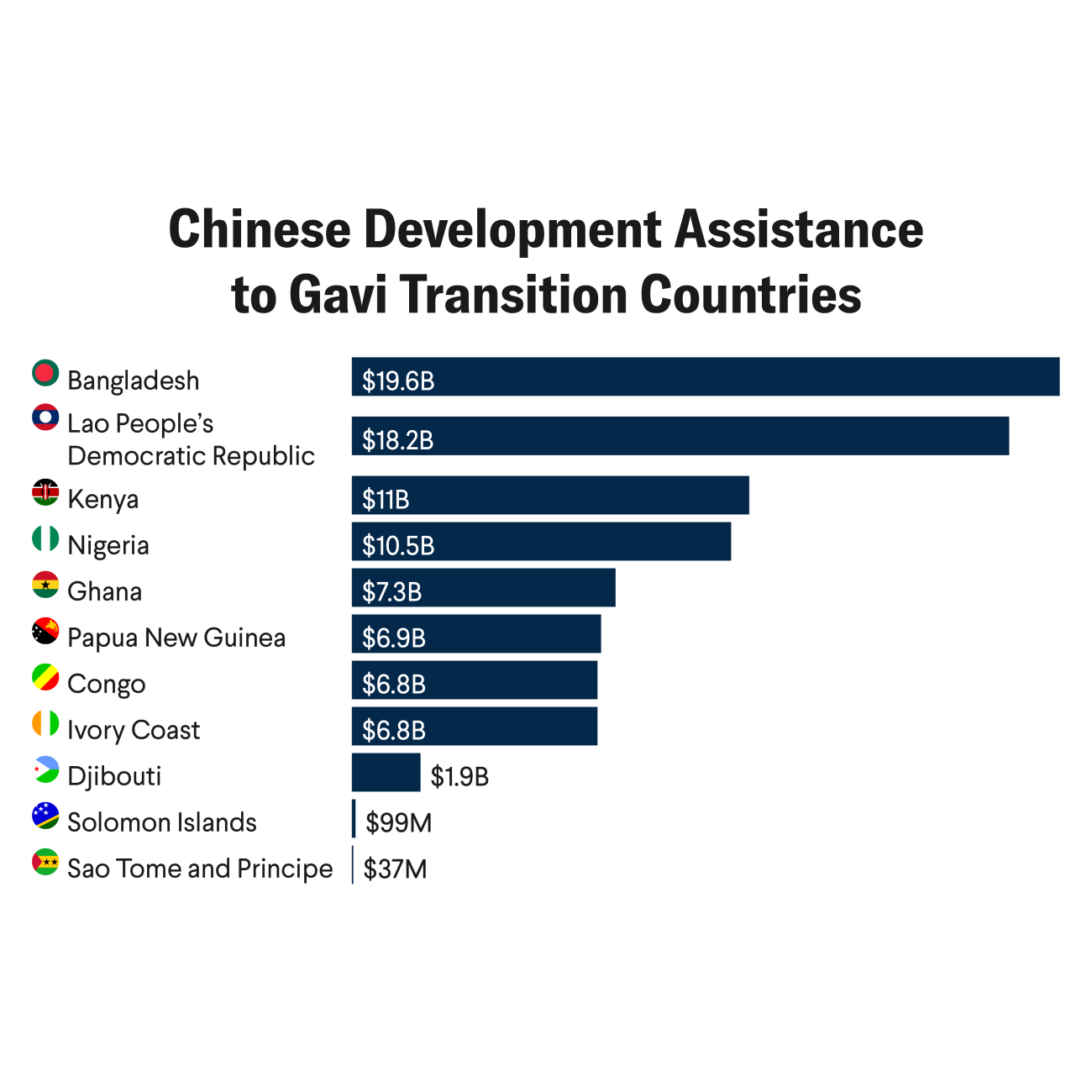

Of the 72 countries to which China has pledged doses, all but two are participants in its Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious global infrastructure project that aims to increase Chinese influence, develop new investment opportunities, and strengthen economic and trade cooperation across 139 countries.

The link between the Belt and Road Initiative and donations should not come as a surprise. China has promoted global health governance, disease surveillance, and international health cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative's "Health Silk Road" since 2015. It also sent masks, medical aid, and expertise to Belt and Road participants earlier in the pandemic. Now, China is using vaccine donations to further elevate the Belt and Road Initiative in bilateral relations. Preceding or immediately following many donation announcements, Chinese ambassadors and high-ranking officials including President Xi Jinping have met with counterparts in recipient countries to discuss deepening or expanding bilateral cooperation. More explicitly, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi has stated that the Belt and Road is "a corridor for life-saving supplies." Latin American and Caribbean nations, which were slow to join the Belt and Road Initiative, have received few vaccine donations from China.

Another potential motivation for Chinese donations is ensuring or incentivizing support for Beijing's positions on Hong Kong, Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang. In the Caribbean, after Guyana and Dominica accepted donations they reaffirmed their commitments to the "One China Policy." Meanwhile, several Muslim-majority countries, such as Egypt and Kyrgyzstan, offered support to China's positions on Xinjiang and then received vaccine donations.

India, the world's largest vaccine producer, has rivaled China in the scale of its donation efforts—though those efforts have understandably been paused as cases surge domestically, allowing China to assert its influence. Previously, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi pitched its Vaccine Maitri ("vaccine friendship") as a tool to "help all humanity in fighting this crisis," and its Minister of External Affairs even pledged that India will be "the pharmacy of the world." However, India's largesse has not benefited all countries equally. Three-quarters of their donations, or 8.2 million doses, have gone to just eleven countries in East and South Asia. Everywhere else, Indian donations are averaging 70,000 doses per country.

Traditionally, India's aid resources have been limited, and so the country targeted bilateral assistance to a few South and Southeast Asian countries. But since the 2000s, India has evolved into a more far-reaching donor, increasing resources and coordination for assistance. Though India has bolstered relations with and aid to other regions, particularly Africa, Prime Minister Modi's "neighborhood first" approach to foreign policy has further intensified the focus on South and Southeast Asia in order to counter China's growing influence. Beyond South and Southeast Asia, New Delhi aims to target countries where it can compete with Beijing for influence, focusing non-Asian vaccine donations on countries in Africa and the Caribbean, particularly where there is a sizable Indian diaspora or shared association through the Commonwealth.

Though Russia has pitched its vaccines as the best in the world and gone to great lengths to promote them overseas, it has not made donations a cornerstone of its vaccine diplomacy. Limited by production and economic capacity, Moscow has generally opted for bilateral purchase and licensing agreements, saying that it preferred bilateral deals over COVAX, and offering small donations to only a few nations.

The majority of Russian donations have been in quantities smaller than 20,000 doses (and as small as 20). Many of these have been effectively free samples to countries already considering procurement of Russian vaccines. For instance, Armenia, Belarus, Lebanon, Moldova, Nicaragua, and Vietnam all received donations while procurement or production negotiations with Russia were underway. The largest donations, such as to Uzbekistan, are not coming from the Russian government itself, but from Russian oligarchs or private companies.

In February, Israel provided 5,000 doses to the Palestinian Authority and announced it would gift "symbolic" doses to 20 countries. However, only four of these nations received vaccines before domestic lawsuits halted the campaign. These donations have been criticized as political backscratching and whether they will resume, and in what form, remains uncertain—particularly given questions over Israel's role in assisting the Palestinian Authority. Of the recipients identified by Think Global Health, four recently normalized diplomatic relations with Israel or are moving towards normalization; seven established or were considering establishing diplomatic offices in Jerusalem; and two were in talks to open embassies in Israel. The status of Jerusalem and normalization are unlikely to be the only motivations for Israeli vaccine diplomacy, however. Israel has a long history of providing development aid, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has continued efforts to strengthen foreign relations, especially in Africa and Europe.

Conclusion

Though vaccine diplomacy can help narrow the gap between vaccine-haves and have-nots, the majority of donations given thus far have fallen short. Rather than advance global equity or provide relief to those most in need, donations have cemented traditional spheres of influence. In the world of vaccine donation diplomacy, a friend in need, is a friend indeed.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors would like to thank Thomas J. Bollyky and Erik Fliegauf for their assistance.

This tracker was first published on March 25, 2021.