A long and healthy life starts at school.

According to new research from the Institute for Health and Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and Norway-based Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research (CHAIN), a person's risk of dying drops by 2% with every additional year of education. The protective effect is similar to that of avoiding smoking on lung cancer or eating vegetables on heart disease. IHME-CHAIN's research is part of the social and economic branch of the latest Global Burden of Disease study, slated to launch later this month.

"The relationship is clear," said Claire Henson, IHME researcher and colead author on The Lancet study. "Investments in education are investments in health."

Although researchers are still working to disentangle the factors driving the impact of education on longevity, the link between educational attainment and socioeconomic outcomes including greater income, health-care access, and housing is well established. Learning could even slow the pace of biological aging and delay the onset of aging-related diseases, according to a recent study at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health.

More Schooling Correlates With Longer Lifespans

Each additional year of schooling leads to a drop in mortality, and in high-income countries the effect is greatest in men

IHME-CHAIN found that education offers a slightly lower drop in mortality among women than among men in high-income countries, indicating that additional years of school are relatively less likely to translate to higher earnings and other benefits for women in those regions. The study also revealed that though education is most crucial for the vitality of young people, learning boosts longevity at any age.

"We talk about the strain on our health-care system," said Mirza Balaj, research coordinator at CHAIN and colead author. "One way to alleviate it is to invest in the social determinants of health—education being one of the strongest."

IHME-CHAIN's research confirms a long-held tenet of public health: to improve the health of a population, decision-makers should look beyond individual behaviors and consider the structures that shape them.

An Unequal Playing Field

Given barriers to access and differences in resources, educational attainment varies widely within and between countries, reinforcing existing inequities in health.

According to Terje Eikemo, professor and leader of CHAIN, "[this research] is a matter of social justice."

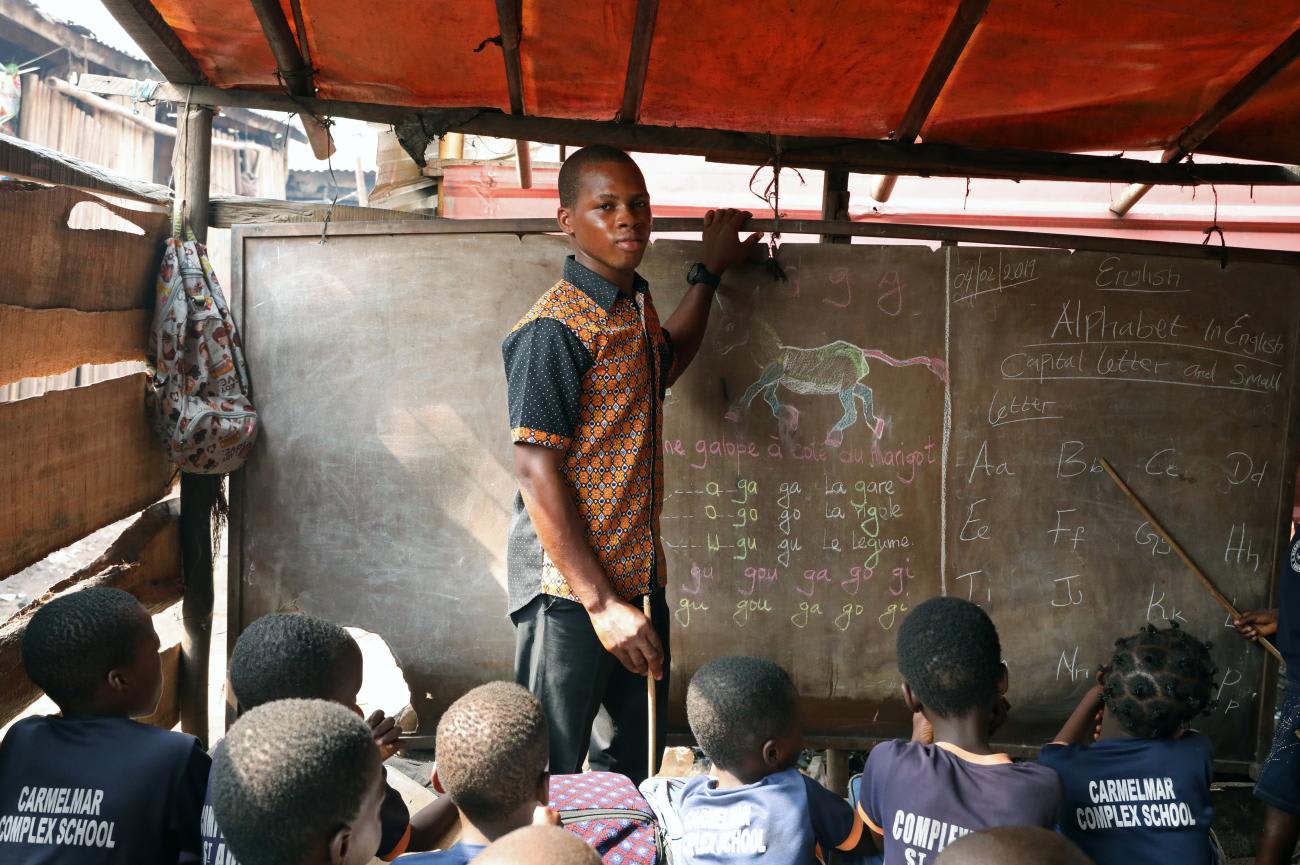

In Nigeria, an estimated 13.2 million children were out of school before 2020—a number that nearly tripled to 36 million during the pandemic. According to the Malala Fund, a nonprofit education advocacy group, girls living in rural areas face major hurdles to remote learning, including more time spent on house chores as well as a lack of electricity and inability to pay school fees.

[This research] is a matter of social justice

Terje Eikemo, professor and leader of CHAIN

In the United States, enrollment in higher education shifts based on race, with just 28% of American Indian and Alaska Native young adults in college relative to 60% of their Asian counterparts. Completion rates are also relatively lower for Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) students than white and Asian students. In addition to differences in income, access, and family responsibilities, students of color often experience discrimination in higher education spaces.

These disparities in learning in mirror disparities in health. Life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa was 10 years lower than the global average in 2019, and AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people experienced larger declines in life expectancy than white people from 2019 to 2021.

Health Inequities Deepen During COVID-19

American Indian and Alaska Natives experienced the largest drop in life expectancy, followed by Latino and Black populations

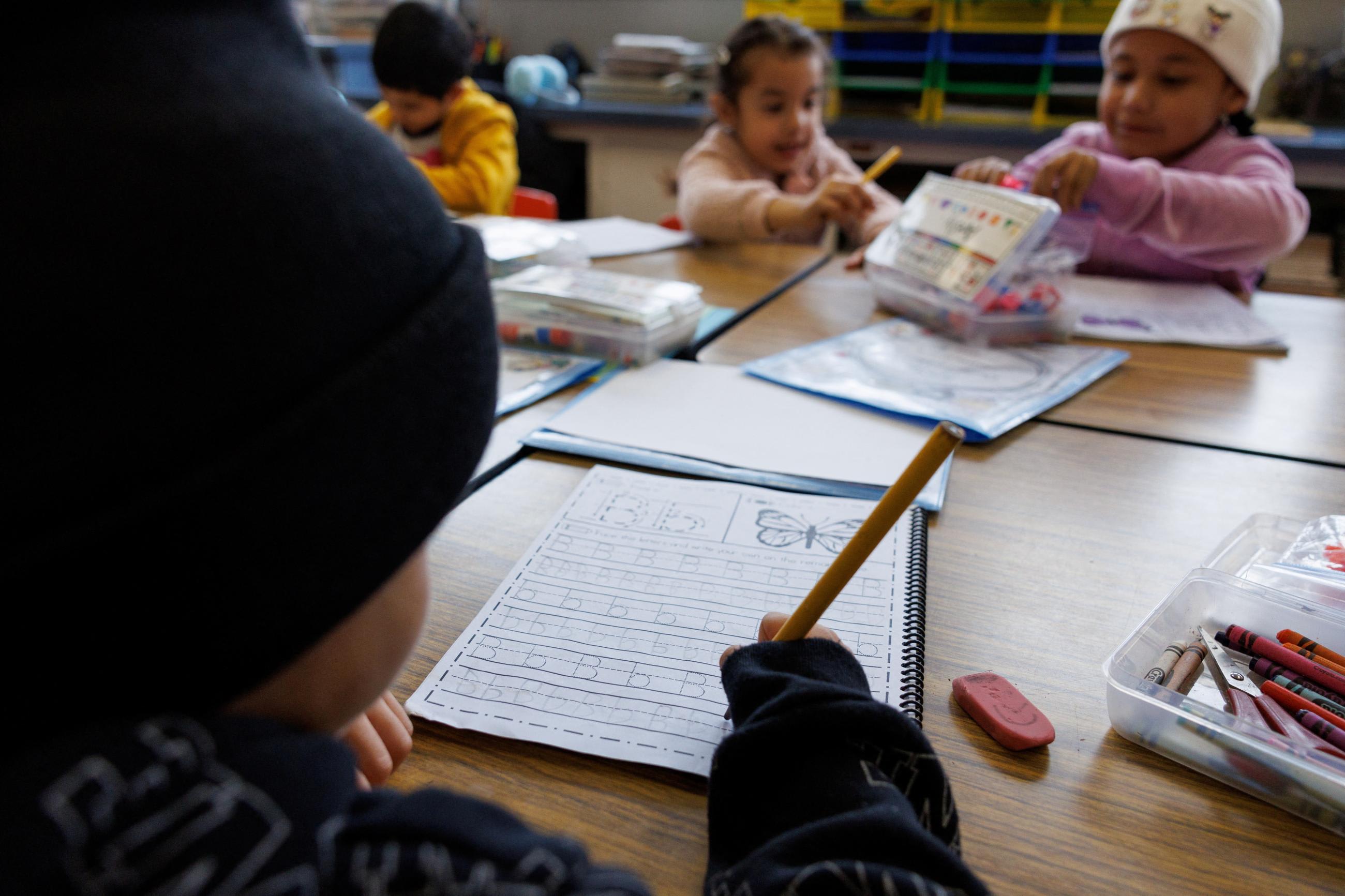

During COVID-19, the gap in educational attainment grew even wider. IHME's Pandemic Recovery Survey estimated widespread learning loss due to the pandemic, with 31% of students in 21 countries falling behind in math and 26% in reading. In lower-income areas, the effect of missing school was even more pronounced. Public school enrollment tanked across U.S. school districts in response to pandemic-related turmoil, causing a number of schools to lay off teachers or close altogether.

Learning loss suffered during the pandemic and its aftermath are likely to have long-term consequences for health. According to Henson, greater attention needs to be given to not only years of schooling, but also the quality of those years. In addition to returning to in-person learning, schools should be inclusive, safe, and have access to quality teachers as well.

Global Disparities in Educational Attainment

Across sub-Saharan Africa, adults aged 25 to 29 spent fewer years in school than their counterparts in other countries in 2018

Investment in Education Pays Off

Given the relationship between education and mortality, the study's authors urge leaders to follow the evidence.

"Health behaviors are socially structured," said Eikemo. "If you're able to alter the structures, you can alter the risk factors."

Some countries have already taken steps toward a structural approach. In Norway, tackling the social gradient in health has been central to policymaking and the basis for the country's 2012 inequity-focused Public Health Act and investments in lifelong learning.

Eikemo hopes their study will inspire similar reforms in other countries, including more robust data collection and cross-cutting investments in education and health to address structural inequities.

"Social conditions we're exposed to at birth accumulate throughout our lives," he said. "We need to put more responsibility on societies and how they are organized."