Like other girls from impoverished regions of Guatemala, Francisca grew up with the belief that women have no right to education. Their role was to take care of home and family. Her mother, Emilia, taught her to cook and clean. Her father refused to teach her how to plant and harvest crops—the tasks she really wanted to learn.

After he abandoned his family, arguing that their farm, located in the northwestern department (district) of Quiché, didn't provide enough revenue for them to survive, Emilia made the difficult decision to immigrate to the United States in 2018. She settled in Silver Spring, Maryland, finding work as a waitress.

"Seeing my mother leave was tough because I didn't know when she would return," says Francisca, now 16 years old. She communicated constantly with her mother by phone, but gradually noticed her mother's demeanor changing. "She hardly minded what I was doing, but I thought this must be normal," she told me in the fall of 2023. "My mother loves me, and she's tired from all the problems she has to deal with."

In the next few years, great numbers of Central American children with immediate family members in the United States will likely seek reunification with their families, according to Sandra Castro, an expert on Central American immigration and associate dean of the College of Professional and Continuing Studies at Adelphi University.

"Hundreds of thousands of Central American families and unaccompanied children have immigrated and will continue to do so because of economic uncertainty, violence, and in most cases, family reunification," Castro adds.

Seeing my mother leave was tough because I didn't know when she would return

That can mean joyful reconnections, as happened with Mynor, age 35, a farmer from Guatemala who left in 2021. Unable to support his family, he trekked north and moved in with his mother-in-law, whom he had never met. She had moved to Germantown, Maryland, decades earlier.

"I got to know her and her husband, adjusted quickly, and developed trust in her," he says. Life seemed stable enough by May 2022, to send for the oldest of his three children, Andy, age 18.

"I arranged for my beloved son to immigrate to the United States by paying a coyote (a people smuggler) with a loan from friends in Guatemala," he explains.

They can now spend time together daily. Both have adapted to the culture, despite being unable to speak English. Mynor works in construction and Andy has enrolled at Seneca Valley High School, which offers courses taught in Spanish. Mynor's wife and other children remain in Guatemala and for the moment have no plans to immigrate.

But reunifications can be painful, too. "Unaccompanied minors are exposed to many traumatic events, including kidnapping, extortion, and physical and sexual assault, in addition to a long treacherous and physically grueling journey," Castro points out.

After Francisca also paid a coyote, chancing the risks, she arrived in Silver Spring in 2021, but found her mother involved with a younger man. "The environment in the household was cumbersome," she says. "My mother's man always looked like he was drunk. He never wanted to create a connection with me."

Emilia was behaving differently too, drinking every night with her new partner. Uncomfortable in that environment, Francisca says she "didn't feel identified with the culture and even less with my new home."

Other children, especially teenagers, will sometimes find reunions fraught. "After reunification, children face several challenges, including rekindling their bond with their parents and creating new bonds with their stepparents," Castro says. "Teenagers have a more difficult time adjusting to their new culture, environment, and individuals being introduced for the first time."

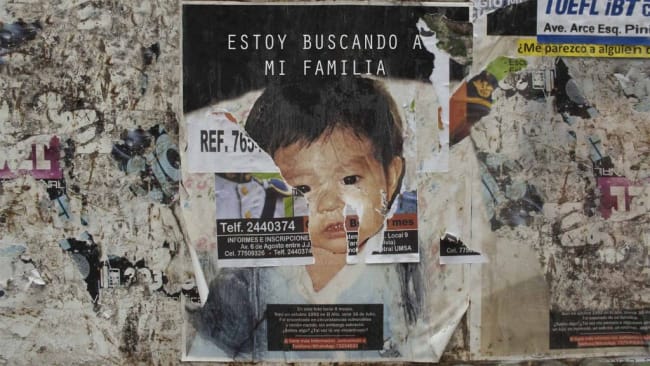

Several immigrant families who now live in American communities experience family reunification after a long separation from their parents, who immigrated before them. Most are now teenagers but were only toddlers when their parents left for the United States and placed them in the care of other family members in their home country.

Those relatives face the challenge of spending time together after reunification and functioning as a family despite efforts to sustain a relationship while separated. Often both the parents and the minors are dealing simultaneously with the trauma they experienced in their country of origin and throughout the journey to arrive on U.S. soil. Thus, these families need assistance adjusting to their new life, strengthening relationships, and addressing the traumas.

Family reunification should be addressed from a human rights approach and the United States continues to have limited and restrictive programs. According to experts, stable relationships between family members who are reunified can reduce the risks of neglect, isolation, and possible exposure to exploitation.

Hope is on the Horizon

One afternoon Andy came home from school, telling his father that Identity, an organization that supports Latinos living in Maryland, has a program that helps with family reunification and cultural integration that could benefit both father and son.

"Through our family reunification program, we work on that link that has been broken, or that can be strengthened even more by living together in a different country," says Monica Wainbarg, senior program manager at Identity.

Most of Identity's clients have been separated for eight to ten years. "When families reunite, they go through a honeymoon process for the first few months," says Tomás Rodríguez, program manager of Identity's family reunification program. "But problems begin after a while, mainly because of the culture shock of introducing a foreign language and traditions."

The goal is to help them know themselves and recognize their trauma

In Identity's family reunification program, children and parents separately attend several sessions. "With the parents, we try to emphasize to recall how challenging it was to immigrate here, how traumatic it was for their children as well," Rodriguez says. "Remind them that if for them it was hard, it will be twice as difficult for their children to adapt to a new culture and traditions."

The goal is to help them know themselves and recognize their trauma, "to learn from their own lives and meet other people that went through the same journey and are experiencing the same challenges here," says Carolyn Camacho, program director at Identity.

Identity was founded in 1998 and its family reunification and strengthening programs are funded by the Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services. According to Camacho, in 2023, 227 minors and parents participated in its programs and approximately 50 families attended multiple sessions to strengthen family bonds.

Programs and efforts across the country to assist reunified families are limited, but Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, Immigrant Families Together, and Hope Border Institute are also helping those families build attachment.

Programs aimed at promoting stable family reunification should focus on upholding human rights and facilitating reliable, safe, and legal avenues for unifying family members. Support plans for reuniting relatives should be easily accessible and provide psychological, educational, and financial solutions.

Providing services for families who have experienced separation and reunification related to immigration is necessary. By creating programs that provide mental health counseling and connect families with other people with similar backgrounds, these types of interventions can succeed in psychological terms and safety concerns.

Given that immigrant families face difficulties when trying to adapt into U.S. culture due to the language barrier and fewer educational and job opportunities, integration programs should focus on recreation programs, mental health, and offering services in Spanish.

Mynor and his son enrolled in Identity's family reunification and strengthening program in 2023. It was especially important to bolster their relationship, Mynor said, because Andy had nearly died at birth after his mother developed a hemorrhage. "I was only 16 years [old], but I remember sitting in the hospital room, praying and thinking, please let my wife and my son survive," Mynor says.

He found the program a crucial help. "I have made friends and further strengthened my connection with my son," Mynor says. "Through this program, I met another Guatemalan. Now we meet constantly, and my son has also made friends of his age."

For Mynor and his son, the last session of the program was the most powerful. "It was a mixture of emotions as I couldn't stop myself from crying, hugging my son, and remembering that I almost lost him when he was born," Mynor says.

Now comes the best time for both: "Andy is a successful student in the United States, and we have made new Latino friends who have been through the same thing."

AUTHOR'S NOTE: Surnames were omitted for the sake of confidentiality.