Despite its mystique as a disease of the ancient world, leprosy—or Hansen's disease, as it's also known—is still prevalent in many places today. As recently as 2018 there were more than 208,000 new leprosy cases globally. Caused by bacterial infections spread by armadillos, the disease is endemic to southeastern U.S. states where those animals roam, including parts of Georgia, Texas, and Louisiana, home to the county's longest running leprosarium—Carville Hospital, which operated from 1894–1999 and is now a museum. This essay by Dallas-based poet Christopher Lee Manes, author of the recently published book of poetry, "Naming the Leper," from LSU Press, recalls Carville and its very personal legacy for him.

My great-great Uncle Norbert Landry was diagnosed "with leprosy," according to an official record, and forced to enter the leprosarium in Carville, Louisiana.

He referred to the old Indian plantation-turned National Leprosarium as a monkey cage

In August 1919, Norbert struggled to find words that adequately described his incarceration, and for several days he delayed communicating with his family. He eventually wrote his first letter from the institution on August 8. In it, he explained to his older brother Edmond, my great-grandfather, that he could not acquire stamps. Norbert's excuse falls flat, however. It only explains why he could not mail the letter, not why it took him more than nine days to write a short forty-four-line message on a piece of post-card-sized stationary.

"Well I am getting along alright but the only thing," he confided to Edmond, "it is a lonesome place. I take my medicine regular and bath too." About his daily routine, the only thing Norbert said was, "We have nothing else to do, so we go and pray to God for our cure."

Norbert died five years later, not of "leprosy" (no one in this history died of that) but of tuberculosis, which he acquired inside the leprosarium. That same year, Edmond was diagnosed with "leprosy," and he, too, fought to find language after being forced in confinement. He referred to the old Indian plantation-turned National Leprosarium as a "monkey cage."

"I am less a leper than I have been" Edmond wrote to his parents in 1926. "I am just trying to adjust myself to this place for it is truly a leper's place."

In 1941 after reports of a leper being "on the street and in the stores" of New Iberia, Louisiana, her brother Albert turned himself in to authorities

Edmond and Norbert's words must have been read as warnings to their younger siblings, because Amelie, Marie, and Albert managed to divert the attention of authorities from their disease for as long as they could. Though they all ended up in the same place. In the case of Marie and Albert, there is a notable difference in their admittance to the leprosarium. Norbert, Edmond, and Amelie died separated from their family. However, when Marie was detected with the disease in 1941 after reports of a "leper" being "on the street and in the stores" of New Iberia, Louisiana, her brother Albert turned himself in to authorities. His act ensured that his sister would not be escorted to the leprosarium under armed guard and forced to live alone among strangers.

Therefore, on a sweltering day in June 1941, Albert and Marie drove their mother Lucie Landry to live with family in Port Arthur, Texas. Then, they headed in the opposite direction to drive themselves to the leprosarium. I cannot say for certain what was discussed in that car on the road, first, to Port Arthur and, second, to Carville. I do know that my great-great grandmother Lucie reportedly never spoke again, and fifteen years later, my great-great aunt Marie, like her mother, began to suffer from a "brain syndrome," which prevented her from speaking.

The word "leper" was written on their caskets and found in my great-grandfather's letters—but among my family members today, the word is rarely spoken

When it comes to describing that place, my relatives and I refer to as "Carville," language becomes difficult. Perhaps, that word is pliable, easily twisted into the comfortable narrative of family lore that we tell ourselves. "They died in Carville" is so much easier to cope with than the particular: "They died abandoned, lonely, and marginalized." The former phrase, it might be argued, offers empty comfort in its elusiveness, but the latter phrase raises accusations and guilt on the past and present—as well as a sense of stigma that reverberates through the years. The word "leper" was written on their caskets. It is found in my great-grandfather Edmond's letters. It is buried in medical jargon on hospital records and has been the source of indescribable pain. Among my family members living today, the word is rarely spoken, but that silence threatens to erase the specifics of our story. Its elimination from public consciousness fails to connect my deceased relatives to those who reside in isolation and "leper colonies" today.

Beginning with my great-grandmother (Edmond's wife) Claire, some in my family refuse to acknowledge and question the facts of this disease or the inhumane effects on people with it. After Edmond's death, his physician Dr. Johansen wrote to my great-grandmother a courtesy card of condolences. "I trust it will be a comfort to you to know that your husband received every attention during his period of treatment here," he wrote. Claire seemingly did not disagree with this statement. She answers Dr. Johansen with her own letter, which ends with, "We are greatly relieved to know that Edmond is not suffering."

What untold suffering did he endure and to what end? Edmond's confinement as well as the incarceration of his siblings seems futile

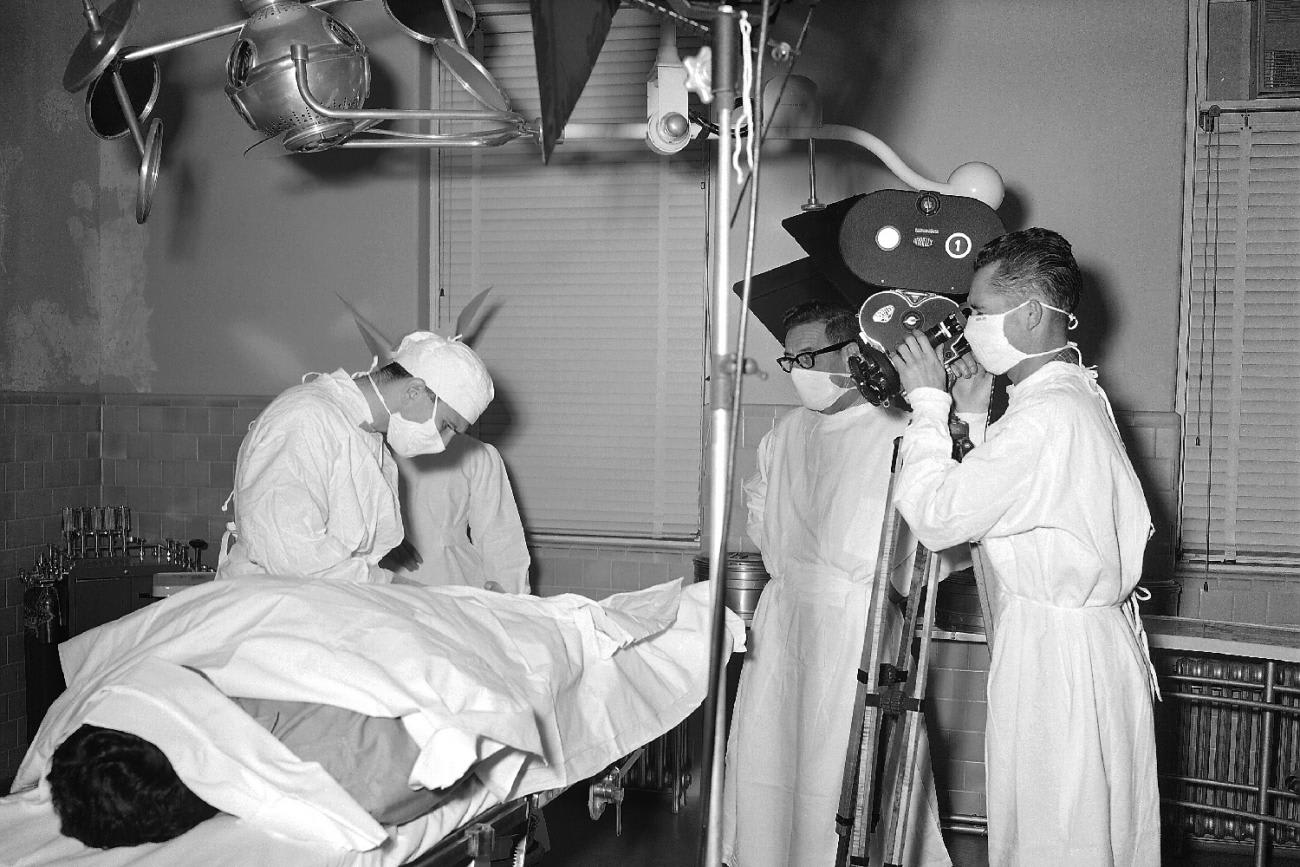

Edmond's feelings of loneliness and abandonment, which he had made explicit in his correspondence to her and other loved ones, are omitted. Though short in length, Dr. Johansen's letter is thick with alarming subtext. What treatment is he referring to? My great-grandfather died there. The medicines and oils used to treat patients with "leprosy" were ineffective and often painful. What untold suffering did he endure and to what end? Medical literature from the early 1900s suggests doctors knew that the disease was neither highly contagious nor fatal, so Edmond's confinement as well as the incarceration of his siblings seems futile. Why were they and any of the patients interred there?

Why were they denied basic human rights? Was it fear and ignorance? The only people who seemingly took "comfort" from their quarantine were those in authority or outside of the leprosarium who did not have to deal with "the truth of the place" about which my great-grandfather and Norbert wrote.

Now, more than 100 years since Norbert first entered the leprosarium, his stories and those of his siblings are at risk of being forgotten. On one hand, few but family know about them. On the other hand, academic discussion about the leprosarium sometimes gives one extreme or the other. It either describes the patients as victims or it writes about their activism but fails to acknowledge their pain.

Poetry, I believe, gives the past a present and future. It allows their words to be read, felt, and relived not with pity but with understanding

My book of documentary poetry titled Naming the Leper deals with these complex and often conflicting perspectives. It begins with the word "leper" in the title, but the poetic cord it strikes, I hope, makes the echo of their experience not relegated to the past. Poetry, I believe, gives the past a present and future. It allows their words to be read, felt, and relived not with pity but with understanding. Norbert, Edmond, Amelie, Marie, and Albert deserve more than a narrow place of genealogical description. Documentary poetry humanizes them and uses their own words to give them life in the present need for advocacy and education about this disease.

Quoted lines in this article come from "The Papers of Edmond and Norbert Landry: Collection 332" archived at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.