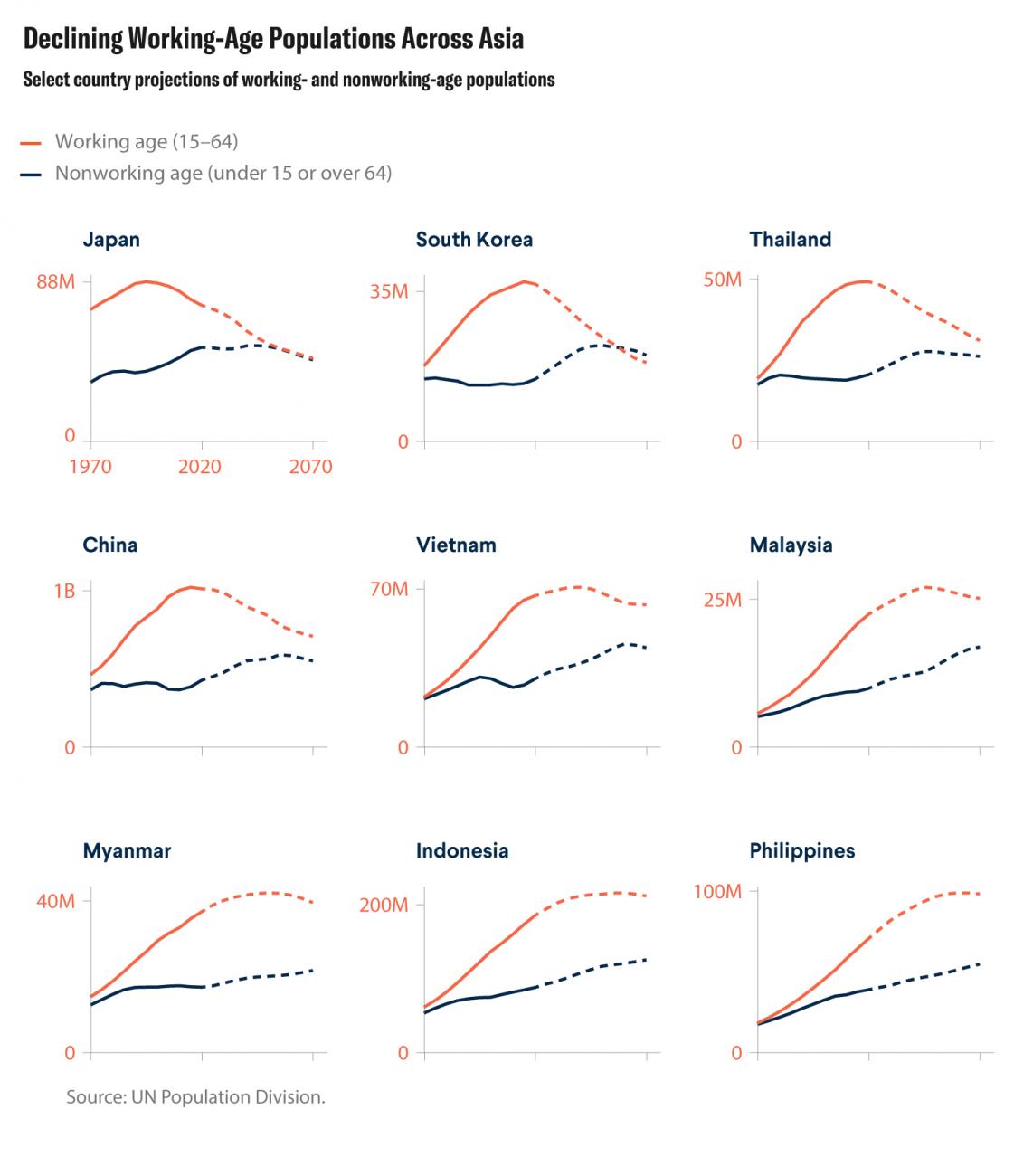

Asia is now at the center of the global economy. The second and third largest economies, China and Japan, as well as some of the fastest growing ASEAN economies [PDF], such as the Philippines and Vietnam, can be found there. But some of Asia's powerhouses must also contend with rapidly aging populations, suggesting that their economic vitality may be waning. The workforces in Japan, China, and South Korea are steadily shrinking. Within decades the nonworking population will surpass the number of people earning wages. This stark demographic future could create significant social vulnerabilities.

What type of vulnerabilities? First, the fiscal burden on the state could grow. Asian governments will need to manage the increasing demand for retirement and pension support with the economic need for ensuring a productive labor force. According to the World Bank, a "range of measures" are needed:

This stark demographic future could create significant social vulnerabilities

"(a) to encourage increased female labor force participation while stemming the sharp decline in fertility, (b) to ensure that older workers in the formal sector do not retire too early as a result of social security and wage-setting systems, (c) to accommodate older workers in the workplace through greater use of flexible work arrangements, and (d) to open up aging labor markets to greater inflows of young immigrants."

Already, some Asian nations are exploring these options. To be sure, the wealthiest Asian countries are well positioned to mitigate these fiscal pressures, but there are both financial and political risks associated with these difficult choices. The GDPs of those Asian nations projected to see the most dramatic decline in their working age populations (Japan, South Korea, and China for example) reveal the increasing share of pension spending.

Another fiscal burden is associated with the need for greater health care requirements for Asia's aging populations. Most Asian nations have access to government-provided health care. Japan has led in the region's demographic shift, with its population falling since 2009. Today, the share of 65 and older citizens is 26.7 percent, and health care and long-term care costs have rapidly increased over the past decade.

In South Korea, where citizens have had universal access to health care since 1989, the demands of the aging population have resulted in a reduced quality of treatment and in some cases, insufficient care for those requiring long-term care. Meanwhile, both Thailand and Vietnam, whose economies are growing at the rate of 3 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively, are struggling to provide health care to their growing number of elderly people who live in poverty.

Another social vulnerability introduced by these aging populations is that Asia's women find themselves at the vortex of a policy debate over the balance between government and social responsibility for the care of those not in the work force. In many Asian countries, women are often expected to take on nearly all elder care and child rearing responsibility even if they also work outside the home. This is especially true in rural areas, but urban women are also affected by pervasive social norms that affect their participation in the economy.

Number of men versus women in Japan who take advantage of a full year of government-sponsored paid leave for new parents

In Japan, for example, where both mothers and fathers are entitled by national law to up to a year of paid parental leave, social pressure has kept the usage rate among men to a mere 6 percent, even as 82 percent of women take such leave. Similarly, care for Japan's elderly has become a source of considerable social complaint. The shortage of publicly available care facilities for children and for the elderly has prompted attention to new policy initiatives in Japan that would ease the strain on women and allow them to participate more fully in the economy. A shortage of available government care facilities has become a major Japanese concern.

Finally, Asia's demographics have also been on full display as recurring natural disasters and human security threats have affected the region's dynamism. During natural disasters, such as earthquakes and tsunamis, the elderly have proven particularly vulnerable. The Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, which affected countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and India, had a disproportionately negative effect on older people, who faced discrimination in receiving relief supplies and whose voices were often ignored in reconstruction efforts.

On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake, which was responsible for the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, struck northwestern Japan, a rural area with a high concentration of elderly residents. That earthquake, the massive tsunami it caused, and subsequent typhoons in Japan have also laid bare the difficulty of evacuation and care for older populations. Today, in China, the vulnerability of older residents of Wuhan to the COVID-19 outbreak yet again has revealed the many ways in which Asia's aging population requires greater social protection.

Asia's policymakers are confronting these new and complex social challenges before many other nations

According to a study published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), a component of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), the highest fatality rates occur among the elderly and those who have preexisting medical conditions.

Asia's aging population presents myriad public policy challenges. Not only does the shrinking workforce impact the economic dynamism of the world's most successful economies, but it has a ripple effect on a wide range of social policies, including health care, gender equality, and disaster management. Asia's policymakers are confronting these new and complex social challenges before many other nations. Their experiences in managing this demographic shift will undoubtedly pave the way for a richer global debate on how to ensure the well-being of an aging society.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was expanded by its authors and the graphic accompanying it was adapted from an earlier post on CFR.org.