In the not-so-distant past, malaria was a term that conjured images of distant, tropical lands—places where the buzzing of mosquitoes and the threat of this deadly disease were an unfortunate reality. Yet, as the world evolves, so do the threats that shape our health and safety. Climate change will alter the distribution of various mosquito species and mosquito-borne illnesses that were once thought of as limited to the Eastern Hemisphere and are already knocking on the doors of the United States, demanding its attention and a swift response. As the country find itself grappling with the aftermath of a pandemic, another public health concern is quietly seeping into our Americans’ backyards: locally acquired malaria and West Nile virus cases.

Although malaria remains rare in the United States, in June, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that four cases of locally acquired malaria were detected in Florida and one in Texas. This marked the first instance of local transmission in the United States in two decades. In July, that number had increased to eight. In August, Maryland confirmed a case for the first time in more than forty years, and authorities reported that mosquitos tested positive for West Nile virus in two locations. In October, the Arkansas Department of Health announced a case of local transmission, making it the fourth state to do so this year. Although ten people may seem insignificant against the hundreds of millions of people living in the United States, they underscore the growing urgency of addressing this emerging threat.

Coined the “world’s deadliest animal” by the CDC, mosquitos are responsible for transmitting diseases like Dengue, Zika, Yellow Fever, and Chikungunya that contribute to more than seven hundred thousand deaths globally each year. As places experience more humid conditions, the life cycles of mosquitoes will accelerate (one mosquito can already reproduce to a staggering four hundred in less than two weeks), increasing the probability of local transmission in the United States. Simply put, the warmer and wetter your area, the more mosquitoes you will likely encounter. Despite these recent cases, the CDC emphasizes that the likelihood of contracting malaria within the United States remains “extremely low.” Prompt identification and response to potential disease outbreaks depends on vigilant clinicians who maintain strong connections with their local public health partners.

Coined the “world’s deadliest animal” by the CDC, mosquitos are responsible for transmitting diseases like Dengue, Zika, Yellow Fever, and Chikungunya

Players in the Fight

To tackle these vector-borne diseases effectively, the United States should shore up its health-care system at the state and local levels. The early days of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed shortcomings in the public health infrastructure, including surveillance systems, and how many health departments were underfunded and understaffed. The pandemic also showed how much we need to use partners “closer to the ground,” including community health workers (the cornerstone of rapid response), community engagement efforts, and diagnostic testing, especially in underserved communities. A case mitigation specialist at the Virginia Department of Health underscores the pressing importance of those measures, stating, “During the pandemic, there was a surge of financial support for our offices. The years since, resources and personnel have certainly dwindled. We are doing our best, but there are still some limitations we face.” Expanding funding and staffing for these departments is critical because they play an indispensable role in safeguarding public health. U.S. officials should not only enhance state and local capacity to address vector-borne diseases but also equip them for effectively identifying, mobilizing, and managing other unforeseen public health threats.

On a federal level, the Division of Vector-Borne Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has taken steps to prepare the nation. According to Tom Skinner, public affairs officer at CDC, these diseases are a top priority in the agencies grand plan for global health security and U.S. preparedness. The agency’s $197,000 budget for vector-borne diseases in FY 2023 is a $15,000 boost from the previous fiscal year. But this isn’t just about a one-time investment; the country needs a long-term national infrastructure, research, and innovation and to build comprehensive vector programs.

The United States Can Take Some Pointers

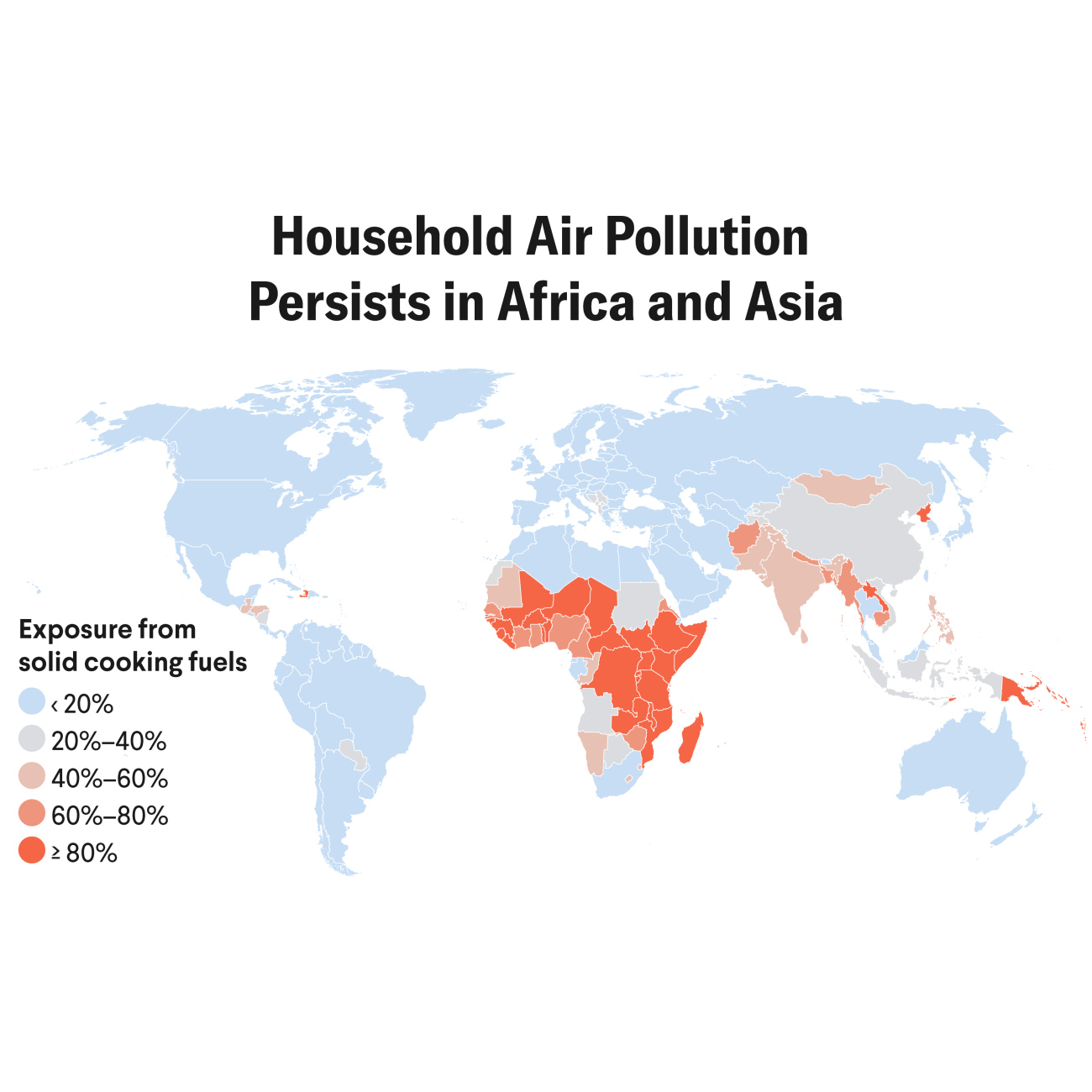

Malaria is an acute burden for Africa, which shouldered 95 percent of the global caseload and 96 percent of malaria-related deaths in 2021. Asia, which has nineteen endemic countries and 62 percent of its population at risk of malaria, ranks second. America can and should learn case control from these countries. Although national infrastructures and outbreaks vary, common strategies and lessons can be applied: India’s National Malaria Control Program has been remarkably successful, showing double-figure case decreases yearly due to its community engagement efforts. The program educates people about the importance of using bed nets, wearing protective clothing, and eliminating breeding sites for mosquitoes. Likewise, the United States can use community health workers and local leaders to engage with at-risk communities, educating them about mosquito-borne diseases and prevention measures.

Rwanda, Africa’s current frontrunner in the fight against the disease, deployed the tried-and-true methods for mosquito control. With increasing use of long-lasting insecticidal-treated mosquito nets, expansion of indoor residual spraying, and subsidization of ACTs, they’ve significantly reduced the number of malaria transmissions, cases, and deaths. Additionally, BioNTech has committed to building mRNA manufacturing sites in Rwanda and Senegal to bolster malaria vaccine production, so countries will do well to “hop on” that viable supply chain route.

The program educates people about the importance of using bed nets, wearing protective clothing, and eliminating breeding sites for mosquitoes

Brazil has used an integrated vector management (IVM) approach, which combines multiple control methods including insecticide-treated bed nets, larval source management, and environmental management. Adopting a holistic IVM strategy could help the United States address different vectors and diseases. This includes coordinating efforts between local health departments, environmental agencies, and community organizations. Malaria was endemic in Sri Lanka for centuries but eliminated in 2012. The foundation of its success was in unique methods, such as hiring regional malaria officers, blanket IRS coverage, conducting insecticide susceptibility tests, and intermittent flushing of canals and waterways.

The reality of the reemergence of mosquito-borne diseases affecting the United States may not come into focus for summers ahead, but the urgency of the situation is undeniable. The United States has the expertise, resources, and the lessons from past challenges to take swift action in bolstering its preparedness. Diseases know no borders and the pandemic demonstrated the vital importance of robust health-care infrastructure, well-funded local and state health departments, and the ability to adapt and collaborate on a global scale. As the United States navigates the evolving landscape of mosquito-borne diseases, it is clear that it should not only address the present challenges but also prepare for the emerging threats.