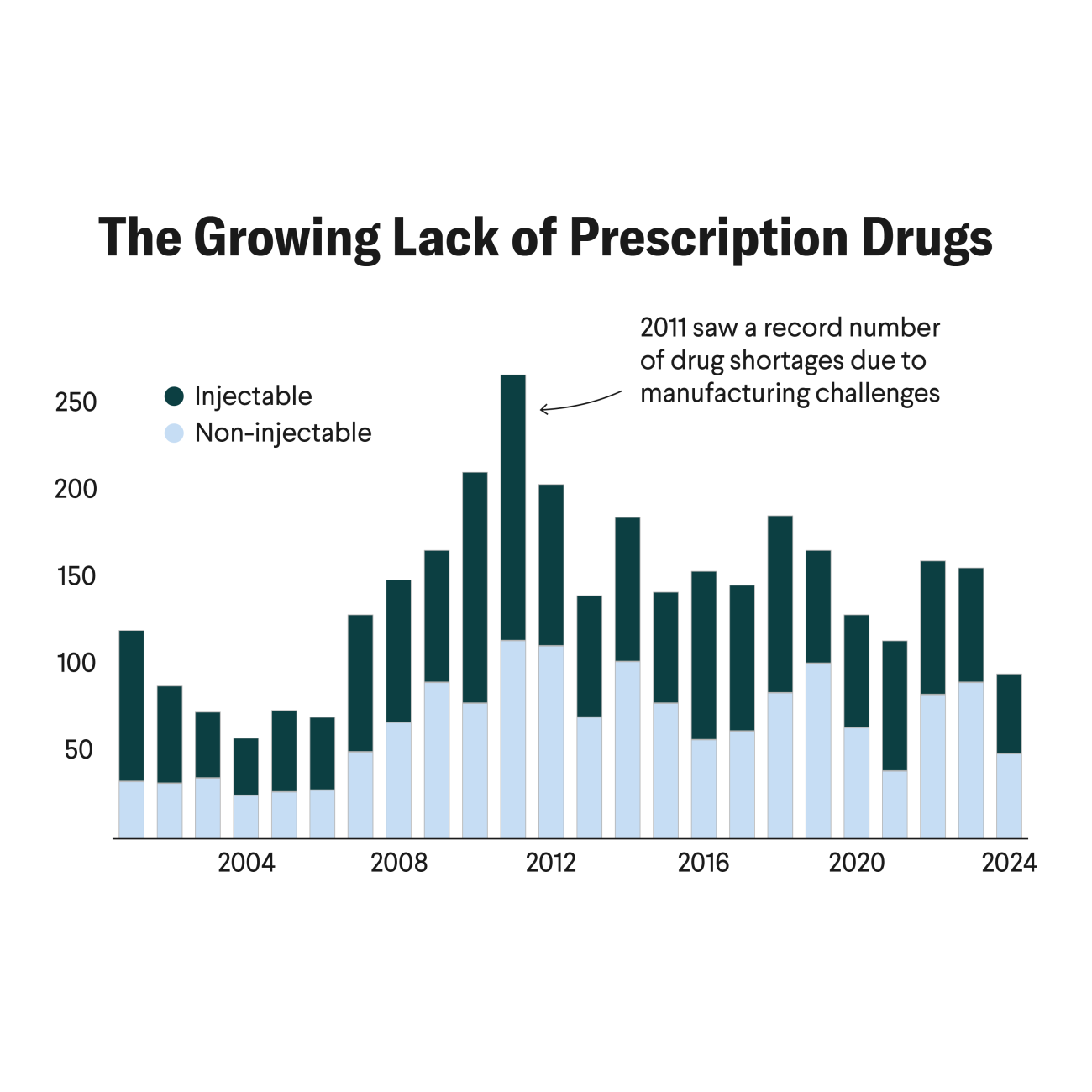

Shortages of generic drugs now and during the COVID-19 pandemic illustrate the vulnerabilities of the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain. The risks of overconcentrating upstream pharmaceutical manufacturing in China and downstream formulation in India has highlighted the need for better understanding of and transparency in the global pharmaceutical supply chain.

The United States, European Union, and other countries are establishing measures to improve supply chain transparency that will help people understand where raw materials are being sourced, where upstream active pharmaceutical ingredient producers (API) are located, and where the finish product is manufactured.

Despite ongoing attempts to add transparency to the U.S. supply chain, such information is not systematically available. Reasons are plentiful, but fragmented and incomplete datasets along with concerns about data being privately owned by companies prevent the use of such information to improve understanding of upstream supply chain risks that can inform policy decisions.

Global health agencies, on the other hand, have achieved considerable success over the last decade with mapping each step of the supply chain and understanding the risks at each step—for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB) medicines.

Any policy instrument, regulatory action, or financing support requires understanding where a supply chain's potential weak points are. This process starts with knowing who supplies the finished product for each therapeutic category, where those suppliers are located, from whom they purchase their active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), and from whom the API manufacturers buy their key starting materials (KSM).

Despite ongoing attempts to add transparency to the U.S. supply chain, such information is not systematically available

The supply chains for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB medicines face various shortcomings at different stages in the supply chain. Those challenges include limited government funding; patients' inability to pay higher prices for finished products; small and unpredictable market sizes, as seen with second-line TB drugs; and small or shrinking demand, as seen with pediatric HIV treatments where prevention of mother-to-child transmission program success reduced the number of children needing antiretrovirals (ARVs).

These deficiencies often manifest as supply shortages and higher prices because fewer manufacturers invest in adequate production capacity. As new products are launched, whether supply capacity can meet market demand is uncertain, raising questions about whether rollout should be slowed to align with supply constraints. Budget constraints have forced ministries of health and global health agencies to find opportunities to improve efficiency using data.

Together, small market sizes and limited budgets made global health agencies more thoughtful and serious about understanding their supply side markets, including upstream supply markets.

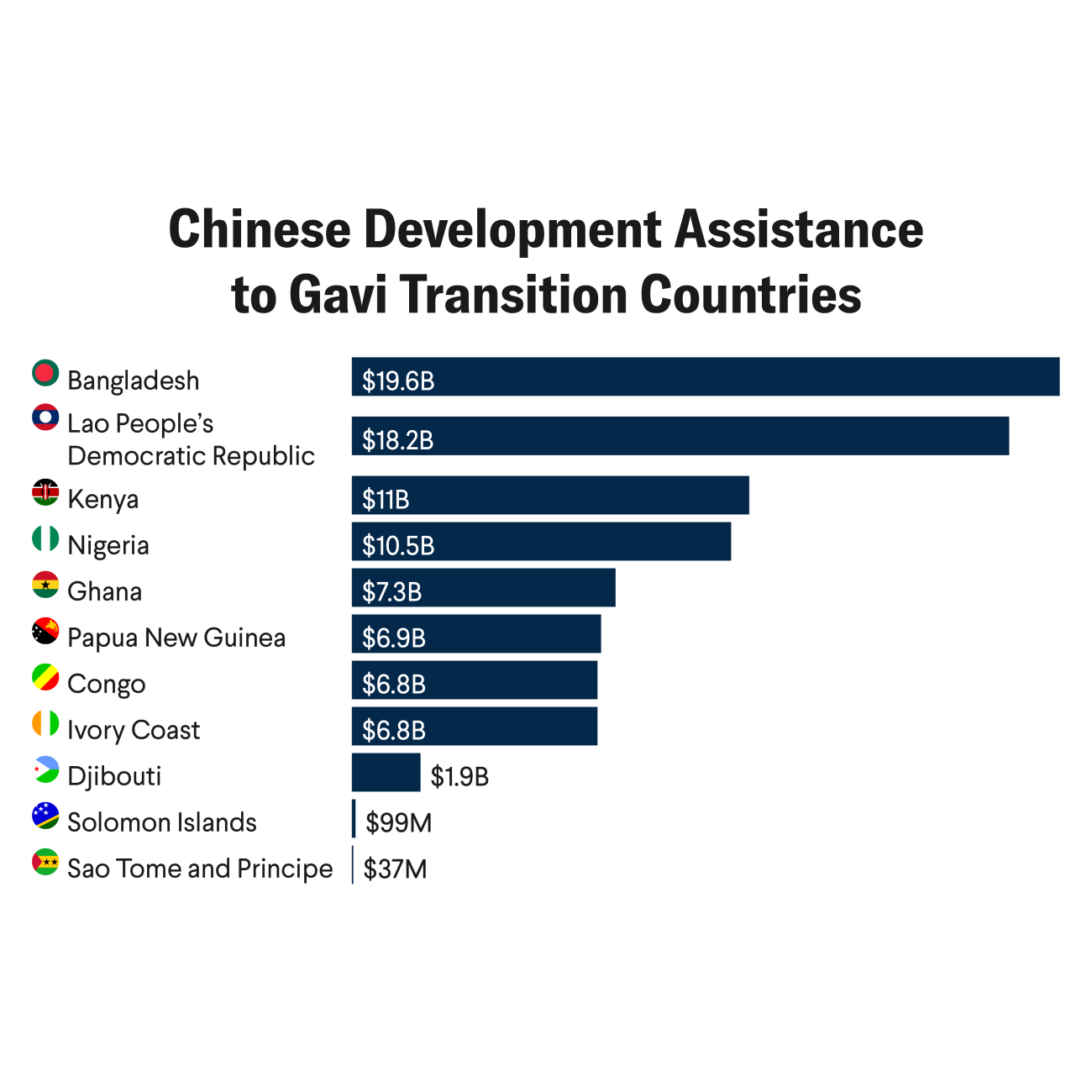

Between 2013 and 2015, with funding from Unitaid, a team of researchers and I began mapping the supply chain for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB medicines from the finished product to the APIs, and in some cases even the KSMs.

You Can't Fix What You Don't See

At the start, we faced the same challenges—lack of data—but by combining trade flow data with procurement data, regulatory data, and information gathered at site visits and from interviews with manufacturers, the team created detailed supply maps such as the following.

To accomplish this goal, our analysis followed the supply chain as if it were a river, starting from its mouth (the finished product) to the source of its tributaries (the KSM producers). We started by creating a simple map based on what could be imputed from existing trade flow data. Then we went to each of the junctions and sources of the tributaries (API manufacturers) to verify flow (production) in that tributary.

We depict that with different dotted lines in the map to be explicit about our degree of confidence in the links between finished product, API, and KSM producers.

Trade flow data and interviews were also instrumental in estimating the production capacity of each plant. Although this task was particularly challenging for multiproduct plants, basic information such as plant size, reactor capacity, and tableting line capacity provided a solid foundation for establishing supply estimates. The regulatory status of each facility, including approvals from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, World Health Organization prequalification, and local country regulators were also documented.

The volume flow and supplier mapping allowed us to estimate the risks of market concentration in suppliers by geography. The Global Fund [PDF], U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Global Drug Facility for TB have carried out similar initiatives to analyze the upstream market. The extent to which these efforts incorporated systematic mapping and capacity assessment, however, varied across the projects.

Mapping Done, So What?

Maps and other data allowed global health agencies to understand where the vulnerabilities were. Products with low-supply risk such as first-line ARVs—characterized by having abundant supply capacity, multiple suppliers, and lower manufacturing complexity—did not require specific interventions. In many cases, knowing which products had lower supply risk ahead of launching a new regimen assured agencies that supply constraints would not prevent treatment if product uptake accelerates.

This case applied to when the HIV regimens shifted to dolutegravir, an antiretroviral. In that instance, Global Fund, Unitaid, and USAID used analysis by the Clinton Health Access Initiative [PDF] to ensure that the supply side was ready for a large-scale, but carefully managed, regimen change.

The Global Fund used similar mapping to conduct internal analysis of the API and KSM markets. That analysis revealed that although capacity for new antiretroviral pills was adequate to meeting the forecasted demand, the availability of finished product suppliers could be constrained by API supply. Many generic manufacturers depend heavily on external sources for their APIs, and some rely entirely on external suppliers.

In contrast, many large, vertically integrated companies have made significant investments in API production to secure their finished product supply chains, whereas others focused selectively on vertical integration for emerging products. Disruptions in API supply and price increases are often driven by challenges [PDF] in securing KSMs. Products with high supply risk—characterized by limited supply capacity, few suppliers, and high manufacturing complexity—required collaboration between global health agencies to effectively use limited supply and initiate measures to expand supply at the API, KSM, or finished product levels. Some products required nonprice factors such as investments in quality and supply security to be considered in supplier selection.

One notable example is the ARV Procurement Working Group, established in 2011 with the aim of coordinating procurement of pediatric ARVs, strategically managing demand, reducing fragmentation through streamlined product selection, and supporting transition of countries. The group's actions considered upstream supply barriers [PDF] as well as the actors and relationships at the API and KSM level.

Another example is the market for artemisinin combination therapies, the recommended first-line treatment for malaria, which relies heavily on agriculturally produced artemisinin, which is primarily grown in China. Fluctuations in farmer growing cycles and demand-side factors have caused significant price volatility for this key starting material, leading to supply-demand mismatches and reduced affordability.

Understanding supply chain dynamics—such as which finished pharmaceutical product manufacturers source from which API producers and the types of contracts API manufacturers use to secure KSM (such as spot contracts or forward contracts)—enabled the Global Fund to prioritize manufacturers that promote long-term agreements with their KSM suppliers. These long-term contracts help stabilize the fragile KSM market by reducing the impact of market demand fluctuations.

Given the focus of global health agencies on volatile markets, they have had incentives to systematically collect and use information that can help supply side markets work more efficiently, anticipate and prevent supply chain disruptions, and improve supply chain resilience.

Unpacking the Differences

The United States, European Union, and other pharmaceutical supply chains have traditionally operated under the assumption of market stability. Historically, upstream supply chain risks have been obscure and thus efforts to organize information about the risks embedded in sourcing materials and the supply chain have been limited.

By contrast, global health agencies have assumed market instability when suppliers are not as interested in supporting the geographies they serve and face a number of market shortcomings. Those agencies thus had a more explicit focus on understanding upstream issues.

The limited number of major buyers in the HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB drug market has facilitated coordination efforts. For low- or middle-income countries, where the disease burden is highest, the primary buyers of those medicines include the Global Fund, South Africa, and USAID. Given there are only a few key stakeholders, coordination and information exchange are more manageable, enabling a shared focus on identifying and addressing upstream supply chain risks common to all parties.

Collaboration platforms such as the ARV Procurement Working Group have been instrumental in fostering this exchange because global health agencies prioritize cooperation over competition. The U.S. market, by contrast, presents greater challenges for such efforts. U.S. buyers operate competitively, often viewing data on upstream markets as a strategic asset, which makes it more difficult to pool information and coordinate effectively.

Understanding Risks in High-Income Countries' Health Supply Chains

The increasing availability of trade flow data and other valuable data streams has provided new opportunities to enhance understanding of upstream supply-chain challenges.

Collaboration among purchasers, however, is essential to fully leverage this data. The four main distributors of medicines maintain sourcing relationships with the generic manufacturers supplying these drugs.

The increasing availability of trade flow data and other valuable data streams has provided new opportunities to enhance understanding of upstream sup

They possess critical insights into finished product suppliers, their capacities, and their API suppliers. Yet these distributors have no incentives to collaborate and share this information. Their individual sourcing and supply data would be far more valuable if combined with data from others, creating a broader understanding of supply chain dynamics. No clear mechanism, however, exists for them to share this information without compromising the commercial interests tied to sourcing and supplier data.

U.S. Pharmacopeia, an independent, scientific nonprofit organization, has started an effort to collect such data systematically. Resilinc, a U.S.-based private company also provides such upstream supply mapping and associated risk to their clients, including companies in the pharma and life sciences business.

The Supply Chain Control Tower is a public-private partnership between the U.S. Health and Human Services Department, other federal agencies, and private distributors that was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to enhance downstream supply chain visibility by aggregating voluntarily shared data from multiple sources. With adequate resourcing and a more systematic approach, such a structure could be used for collecting upstream data on APIs and KSMs and organizing it to proactively understand supply chain vulnerabilities.

For these efforts to truly thrive, however, the U.S. government would need to facilitate greater collaboration between different companies so that multiple streams of data can be pooled. The pooled data would then enable a better collective understanding of supply concentration and risks of disruption. Such detailed understanding is crucial for making decisions and prioritization related to U.S. manufacturing and industrial base expansion for critical pharmaceuticals, APIs, and KSMs. Valuable lessons can be gleaned from how global health agencies have structured and managed these efforts, both technically and with governance.