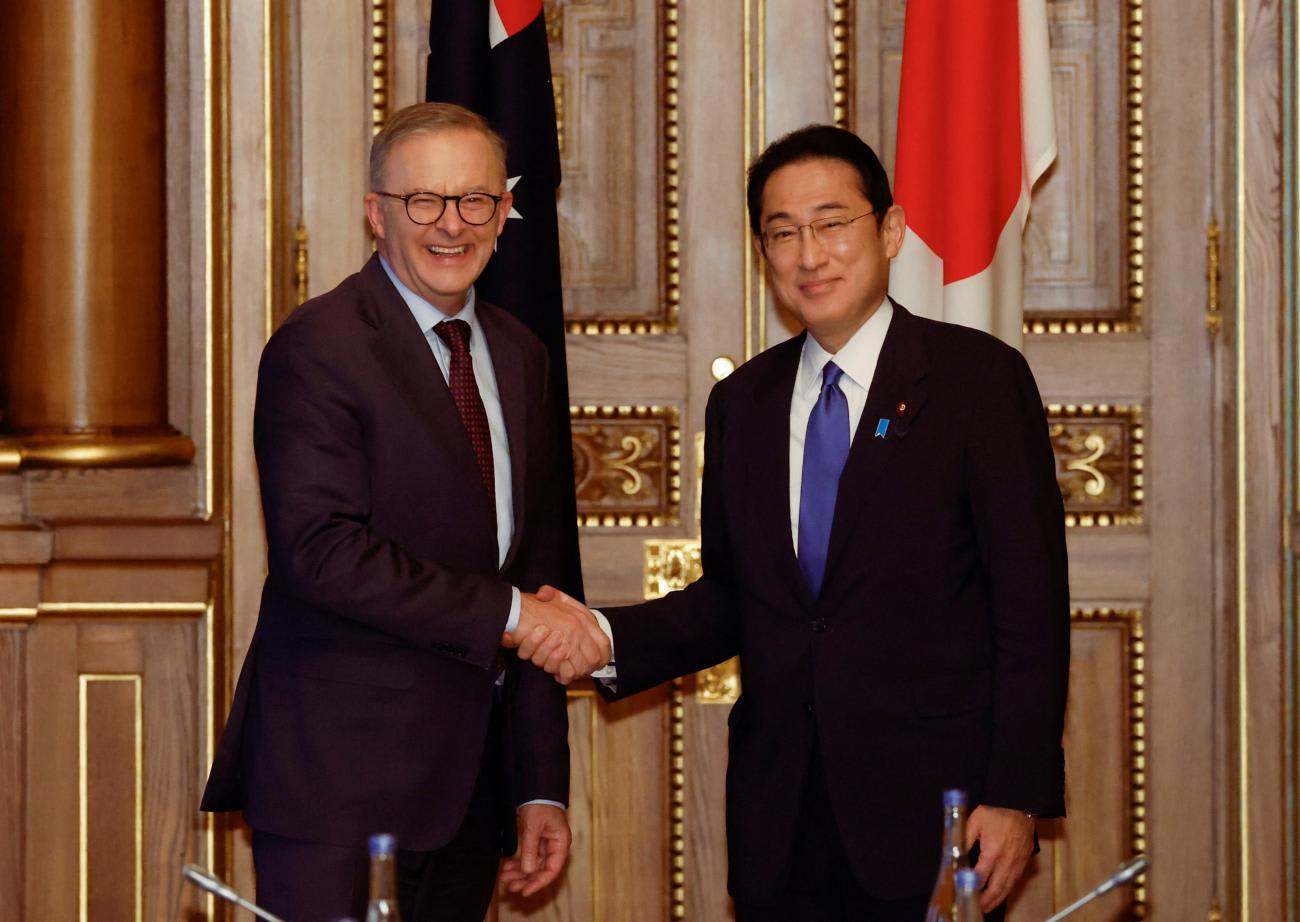

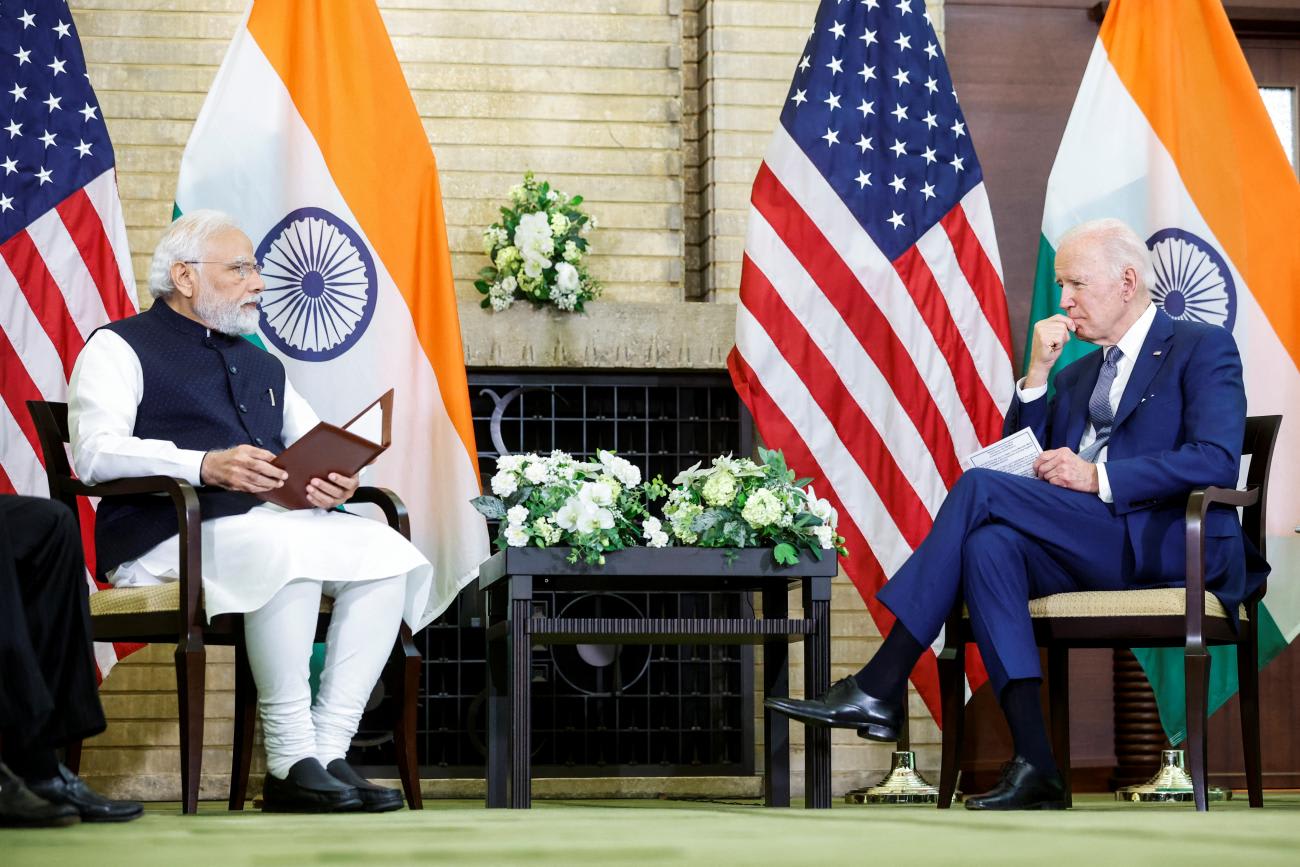

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) summit scheduled for May 24 of this year in Sydney, Australia, has just been canceled. The four Quad countries—Australia, India, Japan, and the United States—will instead meet on the sidelines of the International Group of Seven (G7) in Japan this weekend. The Quad grouping has come a long way since it was established in 2007. Its agenda today includes not just security cooperation but also a host of other issues, including cooperation on international health threats. One important factor, however, has hampered the Quad's ability to act: cooperation gears up when a threat from China is perceived and subsides as the perception fades or the need to conciliate China increases. This behavior has also unfortunately been mimicked in health cooperation. Yet the Quad's health-related cooperation offers an important institution and norm-building agenda that could help construct an enduring partnership among the four countries. Formulating a long-term health security strategy for the Quad is essential, not just for strengthening the partnership, but also for building trust in the Quad's longevity and ability to contribute positively to the Indo-Pacific region.

A long-term health security strategy for the Quad is essential, not just for strengthening the partnership, but also for building trust in the Quad

The Quad partnership formed as a result of the four countries' efforts to coordinate a humanitarian response and provide disaster relief after the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. At the first Quad summit in 2007, the four countries decided to expand their humanitarian cooperation to maritime issues. The driving idea behind the summit was the importance of a free and open Indo-Pacific to all its members. As Prime Minister Abe Shinzo pointed out in an address to the Indian Parliament that year, the "confluence of the two seas" made it imperative to think of the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions as a single strategic space. But after 2007, cooperation through Quad diplomacy waxed and waned. Both India and Australia, for example, had concerns about the Quad being seen as an explicit tool to contain China. In 2017, though, the Quad was resurrected. Quad 2.0, as it came to be known, shared a greater urgency about the rise of China and its growing influence in the Indo-Pacific. The Quad expanded its shared interests to formulate an agenda that included not just security and disaster relief but also development, finance, cybersecurity, and counterterrorism. This wider agenda created space for thinking and interpreting security cooperation more broadly. Then, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived on every country's doorstep.

The Quad Tackles COVID

By October 2020, during the meeting of the Quad foreign ministers in Tokyo, health was mentioned as an issue for Quad cooperation. In readouts released after the meeting, the Quad emphasized the importance of international cooperation to combat the pandemic and spoke of the need to enhance global health security. The pandemic certainly highlighted the urgency of international cooperation to combat the COVID-19 virus, but the immediate impetus behind Quad cooperation on this issue was China's vaccine diplomacy. By mid-2020, China had launched a global vaccine diplomacy effort. The Chinese companies Sinopharm and Sinovac became the main providers of Chinese vaccines abroad. In response, the Quad decided to counter China's vaccine measures. No formal health strategy or concrete long-term policy action was decided per se, but instead, as several senior government and private-sector officials in Quad countries confirmed in private conversations, "health became an issue because of China."

By 2021, China had pledged to offer one billion doses to African nations and 150 million to countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This spurred the Quad's vaccine initiative, which aimed to donate 1.2 billion doses to the Indo-Pacific by the end of 2022. The Quad agreed that the U.S. Development Finance Corporation would make a loan investment of $50 million to the Indian pharmaceutical company Biological-E (Bio-E) to increase its capacity to manufacture up to one billion doses. Some of those were Corbevax (Bio-E's own vaccine developed in partnership with the Texas Children's Hospital); the rest were Johnson & Johnson's (J&J) single dose shots. Bio-E received the funding in 2021 and by the end of the year was able to increase its manufacturing capacity to seventy-five million doses of Corbevax per month. By 2022, Bio-E had installed the capacity to manufacture fifty million J&J doses per month.

The Quad's distribution of these vaccines stalled, however. Reasons for this setback included but were not limited to the pandemic's subsiding and rising vaccine hesitancy related to reports of stroke among those who received the J&J vaccine. Regardless, the upshot was that only one country—India—actually donated vaccines under the umbrella of the Quad. Australia, Japan, and the United States, by contrast, donated through bilateral agreements with other countries. With a large remaining stockpile, Bio-E sold the rest of its vaccine doses to J&J. Because of confidentiality clauses, a senior executive at Bio-E could not confirm in conversation exactly how many vaccines were made for or purchased by J&J or what happened to the unused stockpile after J&J purchased it. J&J did not respond to queries.

Can such a partnership sustainably exist without a focus on China?

Despite the Quad's inability to distribute the pledged one billion vaccines, the initiative still had some successes. Not only did India distribute approximately 290 million doses under the auspices of the Quad, but the initiative itself also demonstrated a public commitment to the Indo-Pacific region. Equally important, it showed the willingness and ability of the four Quad countries to expand their cooperation beyond hard security and to provide public goods. Now, as the pandemic recedes, the Quad faces two broad, strategic questions: Can its members build on their momentum to expand their health security partnership? Can such a partnership sustainably exist without a focus on China?

The answer to both is yes.

The Quad Post-COVID

The fledgling vaccine initiative was later girded by Quad expert meetings on simulating future pandemics and how vaccine and research cooperation could look moving forward. These meetings also divided countries into subworking groups with split responsibilities. Currently, the United States and Japan lead one group, which looks at innovations in regulations, and Australia and India lead another, which looks at pandemic capabilities and responses.

The latter has been particularly relevant to the Quad health agenda. One senior official and health expert in a Quad member country mentioned that despite an effective plan and leadership in place to tackle the virus during the H1N1 outbreak, the vaccines arrived too late. This lesson spurred the Quad to ramp up vaccine manufacturing capabilities during the COVID pandemic. One hope among Quad health officials is that if the Quad systematically focuses on management strategies—including training local health workforces—to detect and respond to pandemics more quickly, the Indo-Pacific region can avoid past "panic and neglect" cycles. The Quad should also think about what to do with capabilities that are revamped or built to meet mass vaccine production requirements. Bio-E, for example, ramped up its capacity to make one billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. Now that the pandemic is receding, expensive, large-scale manufacturing capacities are lying idle. If companies are left to shoulder such large costs, they could be disincentivized to participate in future mass vaccination manufacturing at a time of need. Companies could possibly be helped in various ways to deal with this large expense: the Quad could work with organizations such as Gavi to price the vaccines in a way that would help companies make up the loss, they could continue to buy minimum quantities of vaccines annually, or they could subsidize the costs of the ramped-up manufacturing capacity in non-pandemic times to insure against loss.

The recently canceled Sydney Quad summit was widely expected to answer questions about what the Quad's future health security strategy would involve and how the group would regularize a long-term process for health cooperation. These answers will now be announced at a later date, possibly even at the upcoming G7 summit. But certain elements will be core to any long-term strategy. COVID-19 provided a sharp lesson about the fragility of health systems and the challenges of vaccine delivery. Early detection and limiting any future risk of a slow response will therefore be important to mitigating the risk of a future pandemic. It will also be necessary to talk about "coordination but not duplication." That is, any Quad health security strategy needs to take into account that the Quad is not a formal alliance and therefore does not offer integrated cooperation on health issues in the Indo-Pacific. On the other hand, a solid level of internal coordination is needed so that any one Quad country's efforts and resources are not duplicated by another's.

Ultimately, even though China's growing influence might have spurred the Quad's initial health response, the answer to the Quad's longevity lies in how thoughtfully the group can build a sustainable, inclusive, foundation for future coordination. As COVID-19 demonstrated, viruses cross borders more quickly than wars, and health security is a basic human need, regardless of whether the recipient lives in a Quad country, an ally's, or a competitor's. Moreover, building the plank of health security and purporting to provide public benefits to the Indo-Pacific will strengthen the Quad's position in the region beyond security cooperation.