Since the first cases of AIDS were identified in 1981, much about the epidemic and society’s response to it has aged. Although the global infection rate continues to decline, more people are being diagnosed with HIV as older adults, and those successfully treated with antiretrovirals are living well into their later years.

As AIDS enters what will hopefully be its final chapter, it is fitting to ask: what will the pandemic’s later life look like, and how can we better respond to the needs of aging individuals and societies?

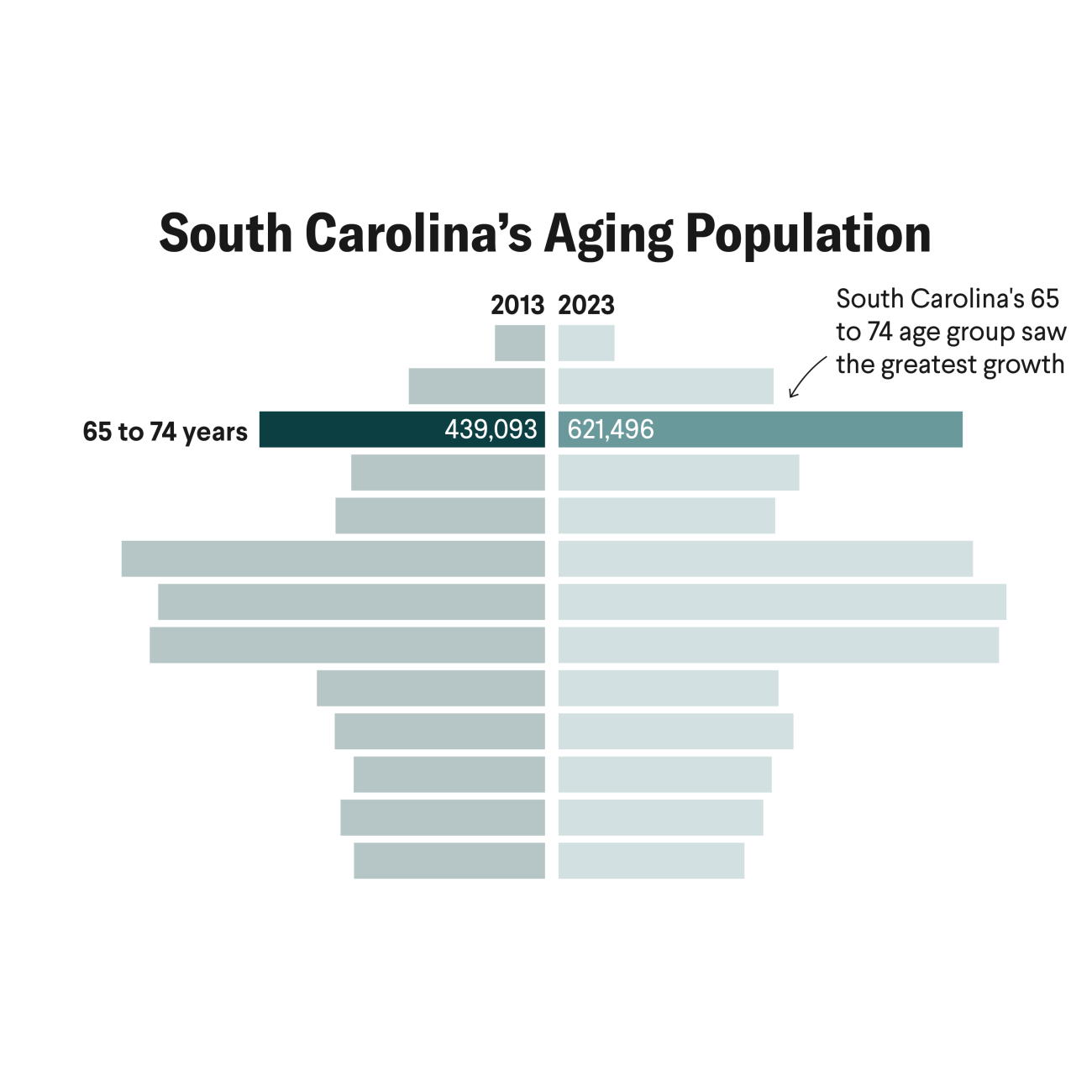

More than half the people being treated under the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) are over forty and more than a fifth are over fifty. The societies they come from are also getting older: because life expectancies have lengthened globally and fertility rates have fallen, older adults make up a rising share of the population in almost every region of the world.

One of her female patients, who tested positive for HIV at age seventy, had never before had her sexual history taken by a doctor

Central to supporting these aging communities is providing people living with HIV better integrated primary care. Longtime Ugandan AIDS activist Dr. Stephen Watiti, who has lived with the virus for decades and turned seventy this year, says that he worries less about HIV than about other chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Speaking at a recent event at the University of Southern California Institute on Inequalities in Global Health, he asked listeners to “not look at us as containers of HIV but as human beings.”

Societal norms have often made it harder for older adults to receive screening and treatment for HIV. Dr. Jepchirchir Kiplagat, a Kenyan physician and researcher, said this was driven home for her when she noticed patients being diagnosed with HIV in later life. One of her female patients, who tested positive for HIV at age seventy, had never before had her sexual history taken by a doctor.

Although the aging of people with HIV should be celebrated—as a sign that screening for older populations has improved and that highly active antiretroviral therapy is prolonging lives—it also reveals critical gaps. Older adults are often still denied information and prompt testing for HIV, such as Dr. Kiplagat’s patient, because of persistent ageism. Delayed testing and diagnosis may allow opportunistic infections to take hold. Further, in fragmented health-care systems, it is more difficult for people with HIV to get the treatment they might need for accelerated aging and frailty as well as comorbid conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. These scenarios put older adults living with HIV in triple jeopardy.

More needs to be invested in programs that account for the needs of an age-diverse population of people living with and affected by HIV. For example, social isolation is both a cause and an effect of HIV-related stigma and ageism, according to a recent commentary in Current Epidemiology Reports, and that isolation is in turn a key determinant of health. People aging with HIV who are isolated from their families and communities and lack social support often experience negative health consequences. Providing older HIV-affected adults with greater opportunities for social interaction—including through education to break stigma and by providing accessible community spaces—can help break this cycle.

At a more fundamental level, the aging of HIV-affected societies should prompt society to rethink the way health care is delivered to all people. Just a few years before AIDS was first identified, the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration highlighted qualities such as integration, person-centeredness, comprehensiveness, and continuity of care as the hallmarks of effective health systems. As the World Health Organization, UNAIDS, and others have recognized, it is time to merge the aspirations of Alma-Ata with the best that has been learned from more than four decades of the HIV response. Person-centered differentiated service delivery, community-based interventions, and a well-supported health workforce form the backbone of successful integration of primary health care and HIV care, according to a recent study in The Lancet Global Health. Evidently with this in mind, last week USAID Assistant Administrator for Global Health Atul Gawande celebrated the thirty-fifth anniversary of World AIDS Day at a primary health-care center in Kenya, noting that the center had not seen any child deaths in five years.

Programs should not only suppress the virus and extend life, but also increase the quality of those additional years

Examples of integrated HIV and primary care abound. In the Haiti PEPFAR Program, HIV services are integrated with maternal and childcare and family planning to reduce stigma. In Malawi, screening for hypertension, cardiovascular disease, depression, cervical cancer, and diabetes are integrated into HIV clinics. Uganda’s PEPFAR programming piloted the integration of noncommunicable disease screening with HIV programming to increase retention of people aging with HIV. These interventions are only possible through dedication to human rights frameworks and flexibility in international donor programs, which should also include further attention to the needs of older adults.

The convergence of primary and HIV care will not only meet the needs of people aging with HIV; it will also point the way to the realization of the human right to health for all. Indeed, the qualities of care needed by people aging with HIV — integrated, comprehensive, stigma-free — are appropriate for all people. Moreover, the social and economic inequalities that fuel the HIV pandemic only accumulate with age, making a human rights-based response to HIV more important in later life, not less.

The HIV response is entering a new chapter. Politics have put the reauthorization of PEPFAR in doubt, novel viruses are testing public health infrastructure, and donor fatigue looms. Now is the time to connect the fight against AIDS to the reality and opportunity of population aging. The legacy of the fight against HIV should be not only the suppression of a disease, but also the birth of health systems capable of handling the next pandemic.

For people living with HIV, who should always be at the center of the response, programs should not only suppress the virus and extend life, but also increase the quality of those additional years.