Climate change and human security are inextricably connected. The ever-increasing frequency and catastrophic nature of climate crises—including wildfires, rising temperatures, and floods—act as a "risk multiplier" for human conflict in the context of existing socioeconomic and political stressors. These compounded threats have serious population health consequences, necessitating resilient political, economic, and health-care systems.

The global surgery community should be at the head of this drive to address climate change and its associated implications for international human security.

Climate Change as a "Risk Multiplier"

As the climate crisis worsens, societies see greater numbers of displaced peoples, an exacerbation of existing socioeconomic inequalities, and increasing geopolitical instability. The UN Security Council formally recognized this link in a report published earlier this year, acknowledging that failure to address instability related to climate change would render the council "out of touch with fundamental threats to international peace and security."

It is easy to appreciate that a community already on the brink of conflict can be pushed over the edge if sea level rise results in flood-driven destruction of homes and infrastructure. However, conflict-affected regions also suffer disproportionately from other effects of climate change, particularly ecological disasters.

As far back as the early 2000s, scientific and political communities have recognized the association between human security and climate change

As far back as the early 2000s, scientific and political communities have recognized the association between human security and climate change. A 2014 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on the mitigation of climate change brought this association to the forefront of discussions outlining both the direct and indirect effects of climate change on human security. A UN Framework Convention on Climate Change report published in fall 2021 elaborated on this interrelatedness, advocating for the tracking of human security parameters as a proxy for achieving goals in climate change adaptation measures.

These effects are being played out in real time in Ukraine. Radiation spikes experienced as Russian forces captured the Chernobyl power plant and a refugee crisis resulting from mass forced displacement have understandably caused international alarm. Yet with Ukraine being one of the biggest external agricultural exporters to the European Union, the effects on international food security have garnered significantly less attention. Add to this, the implication of disintegrating international collaboration, the divestment of funds from climate change efforts to military operations, and the opportunistic move by some leaders to renege on short-term emissions commitments, and it's clear that conflict spells climate disaster.

However, the impact of climate change on human security refers not only to conflict but also encompass food, energy, and economic security in addition to health threats from pandemic diseases and natural disasters. For example, rising warm season temperatures and changing precipitation patterns across the globe are reducing crop yields and threatening already tenuous food security. The newly published 2022 IPCC report further highlighted the multidimensional effects of climate change on health, food and water security, and migration patterns.

The consequences of these "multiplied threats" require a coordinated approach across all sectors of our society, including health care. For health-care providers, this effort requires a transition from a focus solely on the direct impacts of climate change on individual health, to a broader engagement with the impacts on population health and human security. This shift in focus is highly reminiscent of the challenges communitues continue to face in their responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Leveraging Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

Addressing climate change will require a global, coordinated effort on par with the strategies required to address another "risk multiplier" - COVID-19. As a global surgery community, we should learn from the successes and failures in our response to COVID-19 as we tackle climate change.

The 2021 Lancet countdown identified how the COVID-19 pandemic exposed vast inequities in resilience between communities confronted with health emergencies, highlighting the need for national and international coordination and preparedness. Countries fighting hardest to cope with the catastrophic effects of climate change often lack the resources to respond to pandemics, and in the case of COVID-19, are still struggling to vaccinate their populations. The global surgery community is awakening to the time-critical need for improvements in health-care system disaster preparedness. Resilient surgical systems can significantly reduce the impacts of both sudden onset disasters or pandemics and the slower effects of climate change. To build such systems requires the prioritization of stable supply chains for surgical equipment, anaesthetic medications and oxygen; expansion of a multi-disciplinary surgical workforce through regionalized specialization training programs; and investment in and maintenance of climate-friendly and -ready health-care infrastructure.

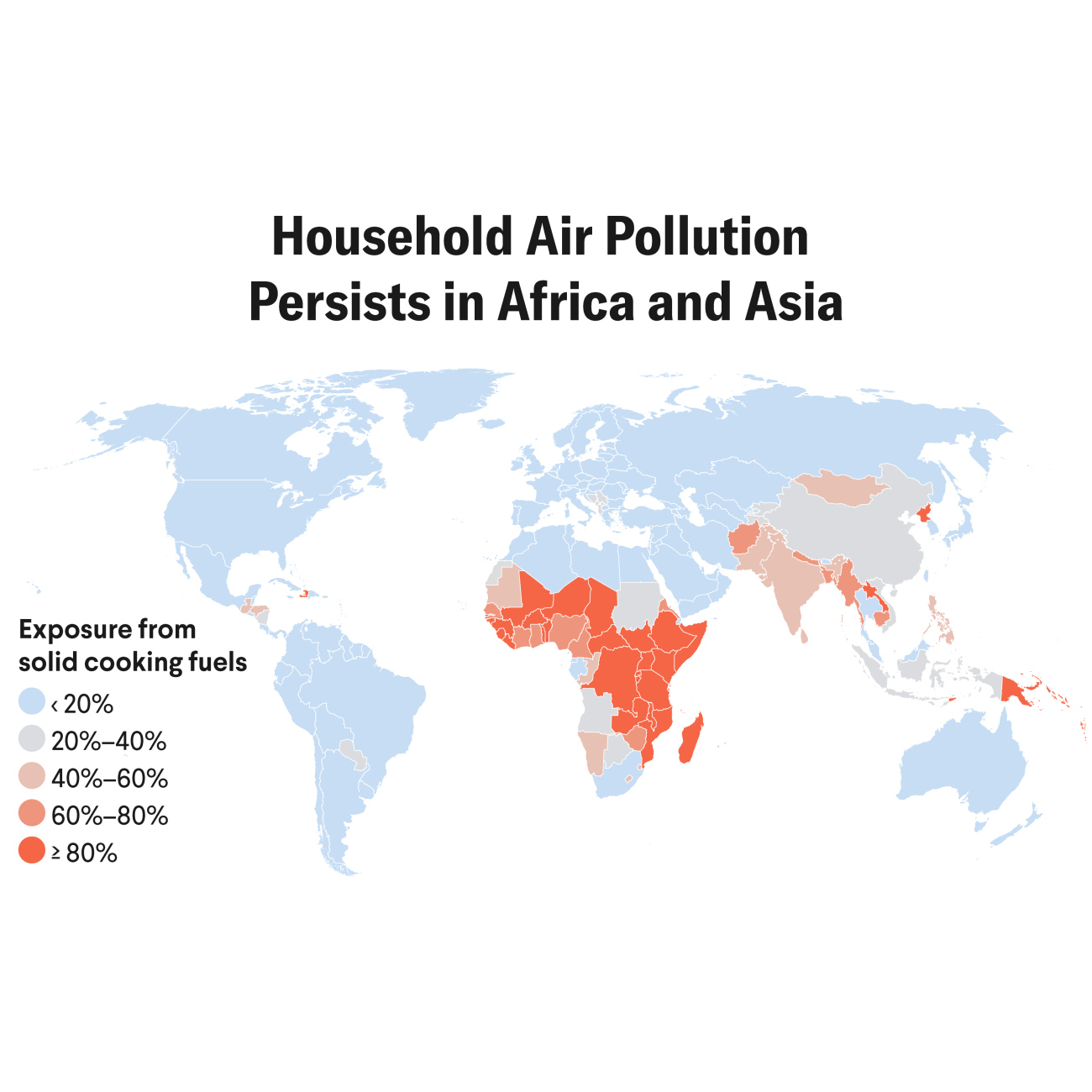

Yet the regions most affected by climate change such as the Pacific Island nations, and many countries across sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia tend to have the greatest surgical capacity shortfall, with frequent issues related to supply chain deficits, and bottlenecks in workforce capacity. This became unavoidably apparent to the world during the COVID-19 pandemic when, for example, critical oxygen shortages in India led to hundreds of excess deaths. The compounding effects of climate change will only serve to exacerbate these existing deficits in access to surgical care realized through impacts on surgical infrastructure and workforce.

The Pacific Island nations, and many countries across sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia tend to have the greatest surgical capacity shortfall

Global Surgical Systems as a Response to Climate Change

Thirty percent of the global burden of disease is surgical; more than that of malaria, HIV/AIDS, and TB combined. Such surgically treatable conditions include traumatic injuries from road traffic accidents, obstructed labour or bleeding post-delivery, life threatening infections of the bones and soft tissues, and debilitating congenital abnormalities such as cleft lip and clubfoot. In 2015, the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery highlighted a significant shortfall in surgical provision worldwide with an estimated 5.3 billion people lacking access to safe, timely and affordable surgical care, and 143 million more operations needed annually. This shortfall is most concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); the regions most negatively impacted by climate change. Increasingly, LMICs are formulating National Surgical, Obstetric, and Anesthesia Plans (NSOAPs), which entail structured policy initiatives intended to incorporate surgical health care into national health structures, in an attempt to address this need. As we strategize to massively scale-up surgical systems worldwide, it is imperative to incorporate climate change-related health security concerns into the agenda. Surgical, anesthesia, and obstetric leaders have not only an opportunity but also an obligation to do so.

Plans for the scale-up of surgical services must reflect the importance of the complex relationship between health, climate change, and human security. The World Health Organization (WHO), through its health and climate change toolkit and operational framework advocates embedding climate change adaptation strategies within national healthcare planning. Surgical care providers contribute significantly to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions yet also have the ability to respond to trauma, emergency, and critical care needs associated with climate-related disasters. As global surgery advocates we have a vital role to play in both mitigation and adaptation, reducing health care related GHG emissions and coping with the effects respectively.

As a first step, surgical leaders must modify their frameworks. National Adaptation Processes (NAPs), established under the UNFCCC agenda, are a means by which LMICs can identify medium- to long-term strategies across policy sectors. The WHO advocates for the formulation of Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments (V&As) and specific Health National Adaptation Processes (H-NAPs) within NAPs. These H-NAPs must be comprehensive and incorporate surgical system planning. In tandem, NSOAPs must integrate climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. The Pacific Island Countries are implementing this approach and leading the way in innovative endeavors and advocacy using their collective voice as the "Blue Continent." Despite demonstrating the collective power of low- and middle-income countries in driving through the Paris Accord of COP21 in 2015, these same countries most affected by climate change largely rely on adaptation strategies given their limited ability to mitigate emissions compared to high-income countries.

High-income countries have a moral responsibility to protect the human security needs of the most climate-vulnerable communities. HICs, as the major contributors to GHG emissions and climate-destructive practices, should not be allowed to take a passive back seat. Integral to this effort, the global surgery community has an opportunity to break from its neo-colonial roots. Surgical, anesthesia, and obstetric providers have an obligation to advocate for climate responsible practices in their own operating rooms, and beyond. In doing so, we will promote justice for those who are most at risk of being devastated by climate change, a human security threat almost entirely out of our patients' control.