The members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) successfully concluded the twelfth ministerial conference last week with several agreements, including a ministerial decision which makes it easier for manufacturers in developing countries to produce and sell patented vaccines both domestically and in other developing countries.

The decision comes after nearly two years of negotiation on a controversial proposal introduced by India and South Africa to waive intellectual property rights (IPRs) for all COVID-19-related vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics. Designed to boost production and access to COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, the proposal was supported by the majority of developing countries, but initially opposed by many developed countries, who saw it as both unnecessary and counterproductive.

Finalized in the early hours of June 17, the decision bears little resemblance to the original proposal and is certainly not a waiver of IPRs. Instead, members agreed on a text that provides additional flexibilities to "eligible members" and clarifications to the compulsory licensing provisions contained in the TRIPS Agreement.

In a deviation from the existing rules, any eligible member can now legally produce vaccines, even if the purpose is primarily for export

The decision primarily focuses on Article 31(f), which limits authorized use of a license "predominantly for the supply of the domestic market" and Article 31bis, which under certain circumstances, allows for the exportation of pharmaceuticals under compulsory license to members with insufficient or no manufacturing capabilities. More specifically, the decision allows an "eligible member" to limit the exclusive rights provided for in Article 28 of the TRIPS Agreement by authorizing the use of patented IP "required for the production and supply of COVID-19 vaccines without the consent of the right holder to the extent necessary to address the COVID-19 pandemic," subject to the compulsory licensing provisions contained in Article as clarified and waived in the document.

The core of the decision is contained in paragraph 2(b), which allows eligible members to "waive the requirement of Article 31(f) that authorized use under Article 31 be predominantly to supply its domestic market" and thus allows "any proportion of the products manufactured under the authorization" to the markets of other eligible members, including thorough "international or regional joint initiatives" (this wording would include efforts such as COVAX), without the need to seek consent from the rights holder.

In other words, and in a deviation from the existing rules, any eligible member can now legally produce vaccines, even if the purpose is primarily for export, and without the need for the importing member to complete burdensome procedural requirements.

The decision applies only to vaccines—but the decision instructs members to decide whether to extend coverage to the production and supply of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics within six months of the date of the decision—and will remain in force for a period of five years, subject to extension from the General Council.

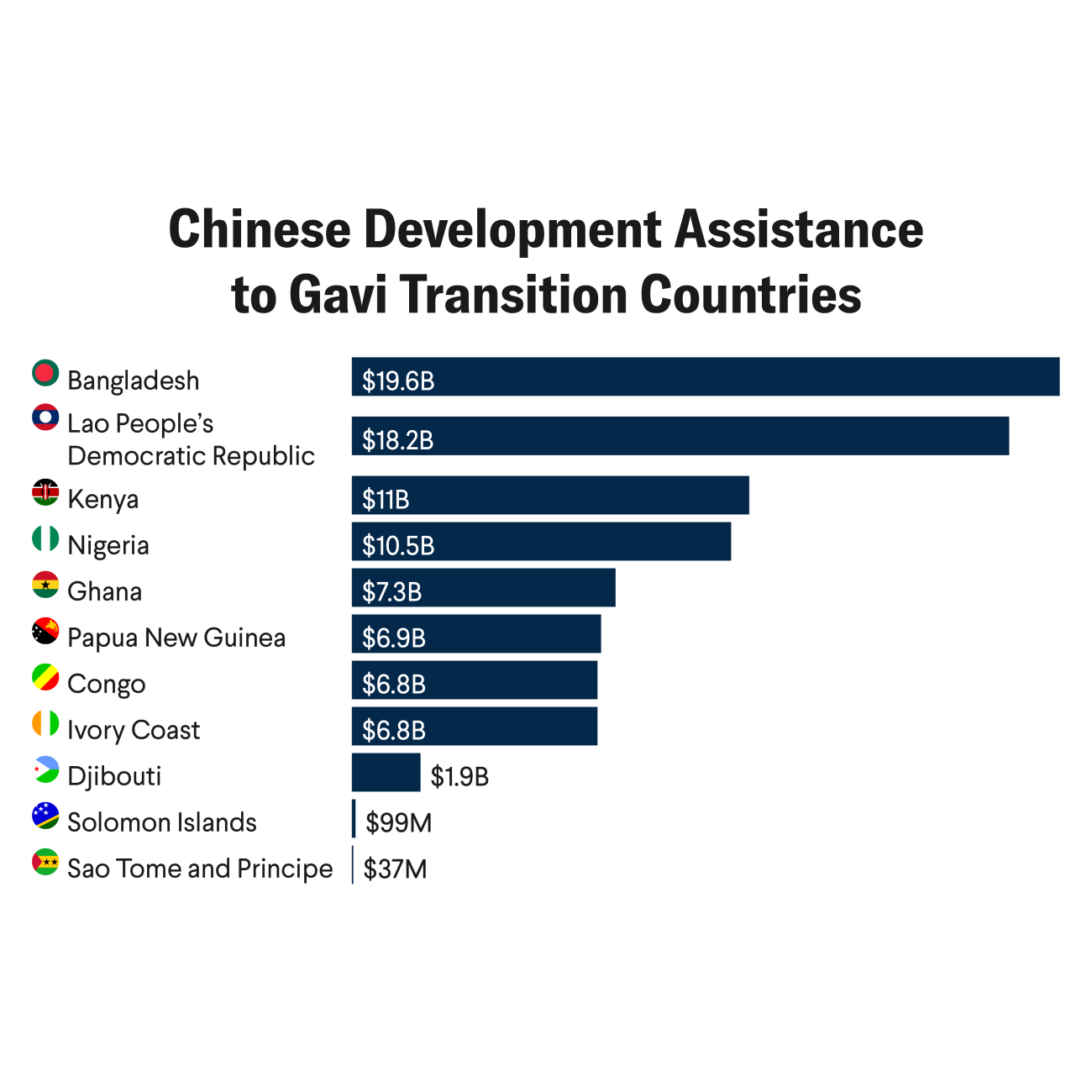

One key issue in the negotiations was eligibility, with disagreement on whether all developing countries should be included in the scheme. While the United States favored explicitly excluding "developing country members who exported more than 10 percent of world exports of COVID-19 vaccine doses in 2021," China unsurprisingly objected to this wording as it would have been the only member captured by the clause. As has been the case in other negotiations, China objected to the form of the exclusion and not the substance. Thus, China readily agreed to voluntarily not to make use of provisions otherwise available for developing countries. The United States was hesitant to accept China’s word, but the issue was resolved through clever textual language contained in footnote 1 that allows members to make voluntary but binding statements, and specifically refers to a meeting date where China voluntarily made such a statement. The final language thus includes all developing country members as "eligible members," but developing country members with existing capacity to manufacture COVID-19 vaccines are "encouraged to make a binding commitment" to not make use of the decision.

Industrial Policy vs. Health

The larger issue regarding eligibility is the call for countries with current production capacity to exclude themselves. If expanding access to vaccines is the purpose of the agreement, one would think that while it would make sense for restrictions on importing members but not for exporting members. At an NGO briefing session held during the ministerial conference, WTO Director-General Okonjo-Iweala seemed to imply that industrial policy was as important for health as she "justif[ied] this outcome on the grounds that it would be desirable protectionism to achieve the objective of promoting vaccine manufacturing capacity in Africa and other developing countries." This response is curious, as it implies industrial policy rather than health was a key determinant for the restriction (and perhaps, the agreement).

The number of COVID-19 vaccines approved for use by at least one national regulatory authority

While the decision should help enhance capacity in certain developing countries and provide an easier path to export production, no one should expect the agreement to significantly change the situation on the ground. But at the same time, the current situation is far different than it was in October 2020 when the waiver was first proposed, or even in May 2021 when the United States flipped its position and began supporting waiver negotiations.

At present, 36 vaccines have been approved for use by at least one national regulatory authority, 10 vaccines in the WHO's emergency use listing, and nearly 60 percent of the world is considered fully vaccinated. More than 20 billion doses have been secured globally at the national level or through the global alliance of vaccine distribution (COVAX), and vaccine supply in 2022 is anticipated to reach 16.7 billion. Vaccine supply now exceeds demand and there are few, if any, credible reports of vaccine shortages. Far from shortages, many developing countries are now dealing with the problem of disposing of unused expired doses and delaying future deliveries, while new manufacturing facilities are struggling to attract clients and receive orders for manufacture.

Moreover, with the COVID-19 virus constantly mutating and the threat of the next pandemic ever-present, members were correct to reject an IP waiver that could have taken away incentives for innovators to continue expending time and resources into research and development. The ministerial decision is imperfect, but in combination with efforts to improve production capabilities, increase voluntary licensing, enhance global distribution, and reduce bottlenecks and blockages, it will go some way to ensuring equitable access to vaccines and therefore be part of the toolbox to help end the pandemic.