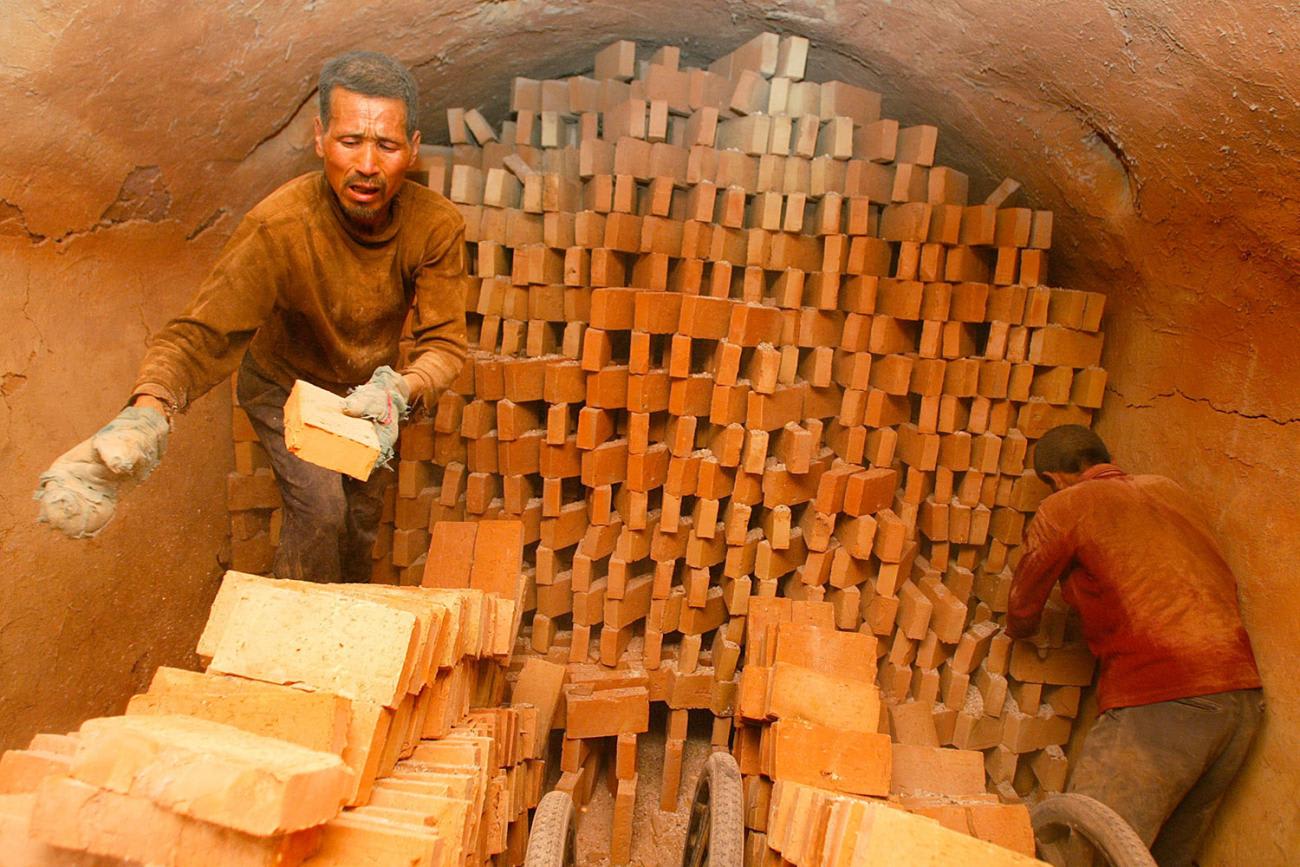

Among all the environmental health issues in China, one of the most common but often poorly documented concern is occupational diseases—chronic ailments and other disorders that arise from the conditions to which someone is exposed in the workplace.

In his book on the history of Cultural Revolution, Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng documents workplace exposures in the Mao era such as "widespread lead absorption, benzene poisoning, mercury poisoning, mercury absorption, and silicosis," but he does not offer any empirical data to substantiate his arguments. Unbridled economic growth in the post-Mao era has resulted in the rising prevalence of occupational diseases. With the proliferation of the so-called township and village enterprises in the 1980s, which were government-backed ventures aimed at creating local industries in rural areas, occupational risks were transferred from the city to the countryside and from the developed areas to developing ones. Meanwhile, urbanization and industrialization attracted hundreds of millions of migrant workers to the cities where poor working conditions and lack of occupational health services only exacerbated the problem.

of China's workers are exposed to work hazards today

According to an official 2009 Chinese Ministry of Health report, in the past five decades there was a seven-fold increase in the types of occupational diseases. The report also said that that the operations of 16 million industrial firms in China exposed workers to poisonous or hazardous conditions, and about 200 million workers—more than 22 percent of the entire Chinese workforce—were directly exposed to dust, chemicals, and poison. While the number of firms presenting occupational health risks dropped to 12 million according to a 2018 study, the number of workers exposed to occupational hazards remains unchanged at 200 million. That number might actually even underestimate the occupational health risks in China due to the low frequency of occupational disease checks and the small number of occupational diseases in the government list.

Among all the occupational diseases in China, pneumoconiosis—a chronic and irreversible lung disease caused by inhaling coal or silicon dust—is the most prevalent, making up more than 90 percent of all work-related illnesses. This is due to China's heavy reliance on coal for manufacturing, domestic use (heating and cooking), and industrial power generation. Despite the rise of alternative energy and the drop in coal's share of China's energy mix, it still makes up more than 60 percent of overall energy use. As the world's largest coal producer, China actually increased its coal production by 243 percent, from 1.02 billion tons in 1990 to 3.5 billion tons in 2017. Often under poor, unsafe working conditions, coal workers in China are subject to long-term exposure to respirable coal mine dust, leading to pneumoconiosis.

Not surprisingly, China continues to have high incidences of pneumoconiosis and silicosis even though other top coal producing countries such as Australia and the United States have seen a significant drop in the annual incidents of lung diseases since the 1970s. About 90 percent of the pneumoconiosis patients in China are peasants turned migrant workers, and a conservative estimate of the number of peasants suffering from pneumoconiosis is six million. Not only can these workers not seek compensation from urban employers, but their occupational diseases may be poorly covered by rural health insurance schemes.

A conservative estimate of the number of peasants suffering from pneumoconiosis is six million

The problem is beginning to raise the eyebrows of Chinese policymakers. One of the objectives of the Healthy China 2030 blueprint unveiled by the government in 2016 is to improve occupational health, including providing health checks for workers exposed to occupational risks for pneumoconiosis and having workers in the coal industry covered by work-related injury incidents. NGOs such as Love Save Pneumoconiosis also have played an important role in raising awareness of occupational diseases and offering assistance to occupational disease patients. However, that is far from enough. In a country where social security rights are often denied and workers still do not have the right to form trade unions, holding employers accountable for healthy and safe working conditions remains a daunting task.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article was originally published on December 12, 2019 and republished in January 2020 to coincide with the official launch of Think Global Health.