Picture this: a crowd of old and young people in a sprawling, densely populated city, huddled around a roadside drug shop. Some in the crowd are coughing into their hands, pressing against a grubby glass counter, and waiting for the drug seller's attention. Others with no cough at all are touching those same surfaces. COVID-19 is affecting everyone around the world in some way. In Europe and North America, ever increasing restrictions are reducing our movements and significantly altering the way we live. However, the response to this pandemic is about saving lives, and, compared to many other countries, people living in higher-income countries have a much easier opportunity to do that. All most of us are being asked to do is spend as much time as possible in the comfort of our homes, and to follow public health guidelines if we develop a persistent cough or fever.

For the vast majority of people living in lower-income countries, this is not an easy task.

I have spent more than a decade working on health systems strengthening in resource-constrained settings to help people with a persistent cough and fever—which are also signs of tuberculosis—have timely access to quality health care. Challenges that people face at every step of their journey—from developing symptoms to finding a medical facility that will have the skilled staff and right equipment to treat them—must be acknowledged and addressed if lower-income countries are to tackle COVID-19 effectively.

More than 80% of people in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have no social protections against illness or unemployment

The first step in correctly managing COVID-19 illness, according to recommendations, is that patients self-isolate at the first signs of any cough or fever. Since these are symptoms of many infectious diseases common in low- and middle-income countries, people may be unlikely to suspect COVID-19. Even if people receive advice about self-isolation, they will likely be unable to do so. Working from home is definitely a notion enshrined in privilege. The United Nations reports that more than 80 percent of people in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have no social protection at times of illness or unemployment. For poor people earning a daily wage, staying at home for seven days after developing a cough, or fourteen days if someone else in the household gets ill, is impractical. It will mean that they cannot feed their families. Most will therefore carry on working, possibly not telling anyone about their symptoms over fears about stigma and repercussions from their employers. This greatly increases the risk of community transmission.

As symptoms become more severe, most people will turn to private drug sellers to seek care. Private drug sellers are vendors who are often de facto health care providers in many low- and middle-income countries, but typically with limited qualifications. They are usually conveniently located, open in the evenings for people to access after work, and they provide medicines cheaply without any consultation charges. In communities with initial COVID-19 cases, people with different health concerns mixing at these private drug sellers could be a disaster in terms of rapidly spreading the coronavirus.

Bangladesh, for example, has less than one critical care bed per 100,000 people, compared to almost seven in the United Kingdom

Another major problem is that drug sellers and other private health care providers are unlikely to be part of any formal government-coordinated network for sharing of public health information or to be updated on recommended management procedures for suspected COVID-19 management. They will also not be set up to alert public health agencies to possible clusters of cases. Gaps in informal health care providers' real-time access to accurate information are critical, especially when they are selling medicines that should be accessible only with a doctors' prescription. With President Donald J. Trump incorrectly claiming that Chloroquine has been approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat COVID-19, people are already beginning to use this medicine without adequate medical supervision, and hospitalizations from Chloroquine overdoses are already being reported.

Finally, people whose symptoms become severe despite medication at home may need emergency care. But often there will be no appropriate ambulance systems, and even if people take private transport, the crisis on access to critical care services in hospitals may be even more severe than in the United States or United Kingdom. Bangladesh, for example, has less than one critical care bed per 100,000 people, compared to almost seven in the United Kingdom.

There are no quick fixes to the proliferation of poorly regulated health care providers that has resulted from years of under-investment in lower-income country public health systems. However, we have an opportunity to adapt policies that have worked in early COVID-19-affected countries, especially since lower-income countries may not exhibit a reluctance to learn from China.

Adaptation of policies will only be successful if we are cognizant of country-specific health system and governance challenges, including the predominant use of informal private health care providers in many countries.

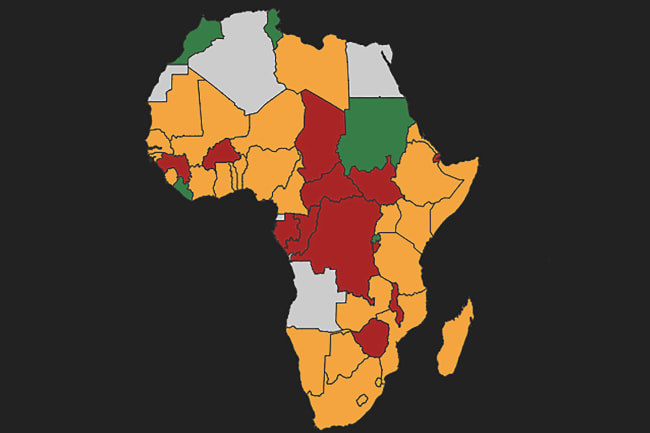

One size will not fit all when it comes to lower-income countries, and a rapid analysis of risk should form the foundation of coordinated actions

Prevention of COVID-19 spread will be even more critical in resource-constrained settings, and strategies could include mobilization of community organizations—including religious leaders – to spread awareness, rapidly mapping and engaging private health care providers, and promoting efforts by governments and employers to financially support those who must stay at home. It is likely that cities with airports or land crossings will become initial hotspots for COVID-19, and it is important to reduce movement of infected people from such parts of a country to rural areas with only skeleton health services. One size will not fit all when it comes to lower-income country responses, and a rapid analysis of the risk factors for COVID-19 spread relevant to each country, led by the government's COVID-19 task force, should form the foundation of coordinated actions.